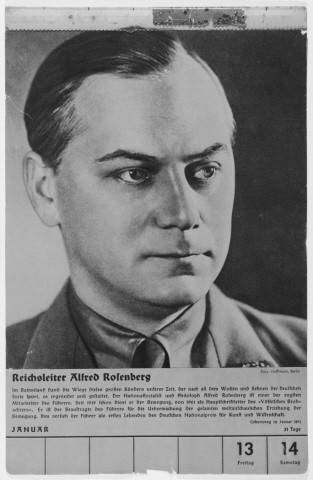

Alfred Rosenberg: Biography

Alfred Rosenberg (January 12, 1893–October 16, 1946) was one of the most influential Nazi intellectuals. In the course of his career, he held a number of important German state and Nazi Party posts.

Background

Born in Reval, Russia (today, Tallinn, Estonia), to an Estonian mother and Baltic German father, Rosenberg studied architecture in Riga and Moscow before fleeing revolution-torn Russia in 1918 for Germany. Already a committed anti-Bolshevik and antisemite, he became heavily involved in the post-World War I ultra-nationalist scene in Munich. In early 1919 he became an early member of the Nazi Party's predecessor organization, the German Workers' Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or DAP). Gaining renown as the author of antisemitic tracts, he quickly made the acquaintance of Dietrich Eckart, one of the early, influential promoters of Adolf Hitler. In an article published in Eckart's own journal, Auf gut Deutsch (In Plain German), Rosenberg made clear a key component of his ideology: the equation of Jews with Bolshevism and communist revolution (“Judeo-Bolshevism”). At Eckart's encouragement, Rosenberg joined the fledgling Nazi Party and began writing for its flagship newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter. He became the newspaper's senior editor in 1923.

Antisemitic diatribes featured prominently in Rosenberg's writings. His efforts helped spread The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in Germany and denounce the Weimar Republic as an aberration born from defeat and manipulated by “Jewish traitors.”

Ideology

On November 9, 1923, Rosenberg participated in the Munich Beer Hall Putsch, which resulted in Hitler's arrest. Tasked by Hitler as interim leader of the Nazi Party, Rosenberg struggled to prevent the Nazi movement's disintegration. After Hitler's release, Rosenberg returned to journalism and began his chief work, The Myth of the Twentieth Century (Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts), published in 1930. Though neither officially translated into another language nor endorsed by Hitler as the authoritative expression of Nazi ideology, the book sold approximately one million copies by the late war years and boosted Rosenberg's standing as Party ideologue.

Based on a selective reading of earlier works of philosophers, neo-pagan authors, and racial theorists such as Houston Stewart Chamberlain, the volume embodied a dichotomist world view that positioned the “Aryan” and the Jewish “races” irreconcilably against one another. All the fruits of Western culture, Rosenberg posited, had evolved solely from the Germanic tribes; yet the Roman “priestly caste” which had arisen with Christianity had combined with Freemasons, Jesuits, and “international Jewry” to erode this culture and with it German spiritual values. While Rosenberg's völkisch arguments and his emphasis on Lebensraum (German “living space” in the East) corresponded with Party ideology, many fellow Nazis found his mystical constructs and his prose hard going. Hitler himself held political reservations about Rosenberg's anti-Christian rhetoric. Until the end of his life, however, Rosenberg remained convinced his racist utopia would provide a recipe for Germany's future as the leading European power.

Before World War II

Following his election to Germany's national parliament (Reichstag) in 1930, Alfred Rosenberg tried to broaden his skill-base by serving as the Nazi Party's expert on foreign policy. Shortly after Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor in 1933, Rosenberg took charge of the Nazi Party's foreign policy office (Aussenpolitisches Amt der NSDAP). More party appointments followed, among them membership in the circle of the Party's top leadership as Reichsleiter (1933), and plenipotentiary for supervising the Party's ideological training (1934).

Compared to other members of the Nazi elite like Hermann Göring, Joachim von Ribbentrop, or Joseph Goebbels, Rosenberg before the war lacked the executive authority that came with a cabinet portfolio. His burning ambition for higher office was undermined by his frequent squabbles with competitors, his inability to forge alliances, and his reputation as an inept administrator. A stepping-stone towards greater political power came in 1938 when Hitler approved Rosenberg's idea for a new, fully Nazified university system (Hohe Schule) that would ground the Party's and the nation's future elite in racist ideology.

Wartime

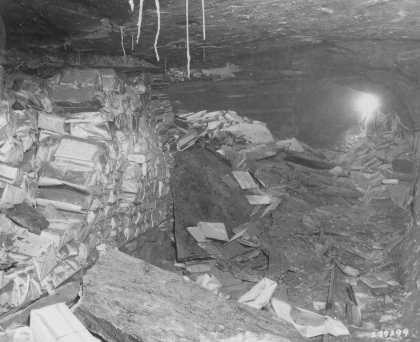

Part and parcel of this system was the “Institute for Research into the Jewish Question” (1941), designed to provide legitimacy for the regime's antisemitic policies by proving the existence of a “Jewish conspiracy” on the basis of books and archival materials confiscated from Jewish organizations at home and abroad.

The war greatly facilitated such activities, for it allowed the organized looting of Jewish libraries, art collections, and other such assets in the countries overrun by the Wehrmacht (German armed forces). It was in this area that Rosenberg first acquired executive authority. Founded in October 1940, his “Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg” [Task Force of the Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or ERR] became the most successful Nazi organization engaged in art plunder. By the end of war, the ERR had shipped almost 1.5 million railcar-loads of artwork and artifacts from German-controlled Europe to the Reich.

In early 1941, Rosenberg moved closer to Hitler's inner circle in preparation for the German attack on the Soviet Union. His upbringing in Russia combined with his unrelenting anti-Communism gave him an air of authority on the Soviet Union that seemed useful to ensure the long-term German domination of this vast region and its systematic exploitation. On July 17, 1941, Hitler appointed him Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories [Reichsminister für die besetzten Ostgebiete], in charge of an area—yet to be occupied—stretching from the former Polish border in the west to the Ural mountains in the east.

As the Wehrmacht advance stalled before Moscow in late 1941, the actual realm of Rosenberg's influence remained much reduced, yet still comprised the Baltic States and parts of Belorussia (today Belarus) and Ukraine. In the occupied regions not under military rule, his ministry installed Reich Commissioners (Reichskommissare) and a complex civilian administration with representatives down to the level of rural districts.

“Final Solution”

From his ministry's headquarters in Berlin, Rosenberg could hear daily reports of the havoc wreaked upon the local population by ruthless German policies aimed at “pacifying” and exploiting the occupied territories. While he criticized the over-harsh treatment of non-Slavic peoples by his subordinates as counterproductive to the goal of winning the war, Rosenberg, as a firm believer in the myth of “Judeo-Bolshevism,” had no problem in targeting members of Soviet elites and indigenous Jews for destruction. The area under his authority was the first to see the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” carried out through the systematic murder of Jewish men, women, and children. By the end of 1941, more than half a million Jews had been annihilated; Estonia, part of the “Reichskommissariat Ostland” was the first German-occupied region declared to be “free of Jews.” Since November 1941, trains with Jews deported from the Reich arrived in the “Ostland.” SS and police officers together with Rosenberg's officials made sure that the deportees were either killed immediately on arrival or exploited in forced labor projects few could survive.

The importance of the events in the occupied Soviet Union for the history of the Holocaust can hardly be overestimated. Despite its constant power struggles with the SS and other German agencies, Rosenberg's ministry played a key role in the evolution of the “Final Solution.” His Reich Ministry was the only government agency to send not one, but two representatives to the notorious Wannsee Conference convened by Reinhard Heydrich on January 20, 1942, to coordinate the next steps towards the mass murder of Jews in German-controlled Europe. When increasingly sidelined from 1942, Rosenberg tried to protect his turf in the face of the Wehrmacht's retreat from Soviet territory.

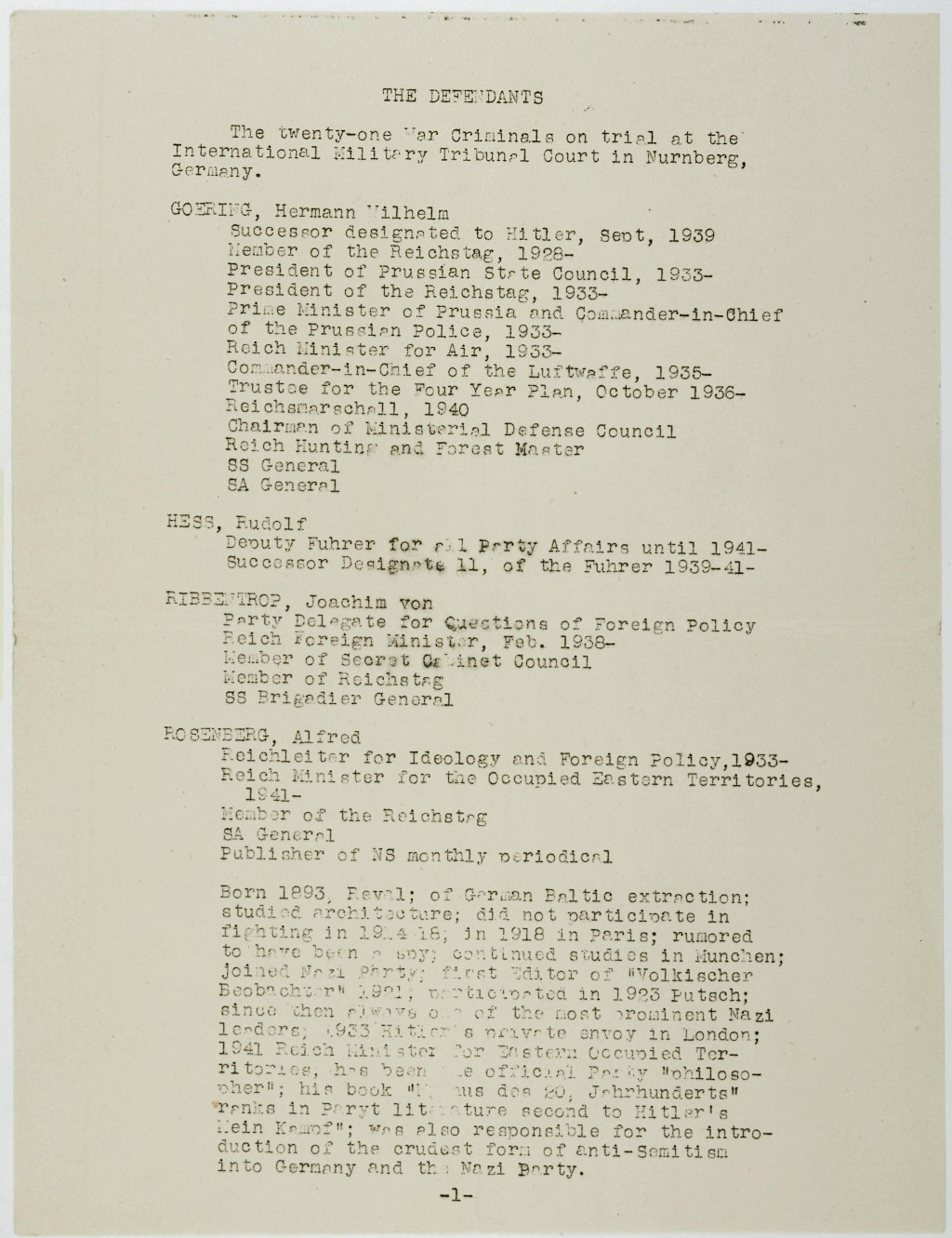

International Military Tribunal

Rosenberg was arrested at the end of the war, tried at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, and found guilty on all four counts of the indictment for conspiracy to commit aggressive warfare, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. He was sentenced to death. Rosenberg was hanged on October 16, 1946.

Critical Thinking Questions

- How did Rosenberg defend his actions and choices at the IMT?

- How do leaders of governments and organizations accused of mass atrocities rationalize their choices?