Adolf Hitler: 1924-1930

For more than three years after his release from prison, Hitler focused on:

- legalizing and reuniting the Nazi Party under his control

- lifting the legal ban on his own political activity, including public speaking

- reorganizing the paramilitary units strictly subordinate to the political leadership of the Nazi Party

Among the new paramilitary formations to emerge in 1925 were the so-called Protection Squadrons (Schutzstaffel—SS), a reincarnation of the pre-1923 Shock Troop (Stosstrupp) Adolf Hitler, tasked with the personal security of Hitler and other Nazi leaders. There was also a reorganization of the hierarchy of the regional branches of the Nazi Party to ensure loyalty to Hitler via the persons of the individual Nazi Party District Leaders, and the establishment of a central Reich-wide political organization under Gregor Strasser.

Nazi Party Political Strategy

The Nazi leadership also dramatically changed the party’s political strategy. Before 1923, Nazi political practice had involved three principles:

- non-participation in national and local elections

- partnerships with non-Nazi conservative right politicians and non-Nazi military formations

- the overthrow of the Weimar Republic by force

After the grassroots reorganization of the NSDAP, which at the end of 1925 claimed just over 27,100 members, the Nazis followed the following principles:

- engagement in electoral politics

- absolute subordination of the paramilitary formations to political leadership

- outreach programs targeting new voters and voters whose grievances establishment political parties were failing to address

- efforts to overcome traditional political, regional, religious, social and class divisions in German society: Catholic vs. Lutheran; Prussian vs. Bavarian; labor vs. management; senior citizens vs. young adults, male vs. female, wage workers vs. professionals; nationalists vs. socialists

Using language developed from discussions with groups of potential voters about their hopes and fears, Nazi speakers developed themes geared to reconcile these traditional areas of conflict and to stoke fear of:

- inadequate national defense and sovereignty

- communism

- enslavement under the terms of the Versailles Treaty to foreign political and cultural influence, control and oppression

- economic decline and job insecurity

- increasing moral depravity in German society, allegedly generated by Jewish and other internationalist influences using the tools of democracy and Germany’s alleged weakness and lack of self-esteem

The Nazis promoted a future of national renewal, in which they would:

- restore Germany’s strength and pride by tearing up the Treaty of Versailles

- establish a self-sufficient and prosperous economy that guaranteed full employment based on talent and national patriotism

- cleanse Germany’s streets and mass/popular media of criminal activity, asocial behavior and allegedly immoral expression

- annihilate the alleged Marxist (Communist/Socialist) threat to German politics and culture

- remove foreign and Jewish influences (political, economic, cultural, intellectual and genetic) that allegedly undermined German society

Nazi speakers made liberal use of the “stab-in-the-back” legend, concocted by German military leaders at end of World War I to evade responsibility for having advocated and continued to fight a war for which they lacked the resources to win, as a demonstration of the way in which these negative influences betrayed the alleged German victory on the battlefield with calculated subversion behind the front, leading to the disasters of the Versailles Treaty and the Weimar Republic.

Hitler’s Social Darwinist vision of human history as an instinct-driven biological struggle between “races” to reproduce in order to survive, to conquer territory on which to settle future generations, and to culturally and genetically “purify” the expanding and multiplying race at the expense of other “races” led him to advocate somewhat unusual foreign policy initiatives for the German radical right. These initiatives included future alliances with Great Britain and Italy. Such advocacy was controversial in German nationalist right wing circles due to Great Britain’s insistence on limiting the development of the German Navy, and Italy’s discrimination against the German population of the South Tyrol. Due to the negative responses among potential voters and political allies, Hitler never published his “second book,” a statement on German foreign policy dictated in the summer of 1928.

1928 Parliamentary Elections

The Nazis tested their new strategy in the national parliamentary elections of 1928, harnessing their paramilitary formations in violent intimidation of voters, particularly on the political left, in order to improve their own prospects. Though Nazi formations initiated much of the politically motivated violence, Party speakers presented it as the consequence of left-wing and Jewish provocation of the “honest” patriotic sentiment of the Nazi rank and file. Despite the almost constant agitation and violence, the Nazis harvested a disappointing 2.6% per cent of the national vote in this still relatively prosperous year under the stewardship of the Weimar Coalition (Social Democrats, Catholic Center Party, German People’s Party, and German Democratic Party). Nevertheless, the decision of the Nazis to abandon putsch attempts for participation in electoral contests as well as their occasional collaboration with conservative nationalist forces on issues such as opposition to the Young Plan in 1929, an effort of international bankers to restructure the German reparations debt into more manageable payments, lent the Nazi a legitimacy and respectability that they had not previously enjoyed.

1930 Parliamentary Elections

With the onset of the Great Depression in the first half of 1930, Nazi agitation began to have increasing impact in the German population. When the Weimar Coalition government collapsed on March 27, the three non-Socialist partners in the coalition, responding to their respective political bases and led by Catholic Center politician Heinrich Brüning, persuaded President Hindenburg to call emergency national parliamentary elections by invoking Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution. With this extraordinary step, the Brüning government hoped to manufacture a governing majority that would first exclude the Social Democrats and then facilitate a revision of the Weimar constitution in a more authoritarian direction that would permanently exclude the political Left from real participation in governing.

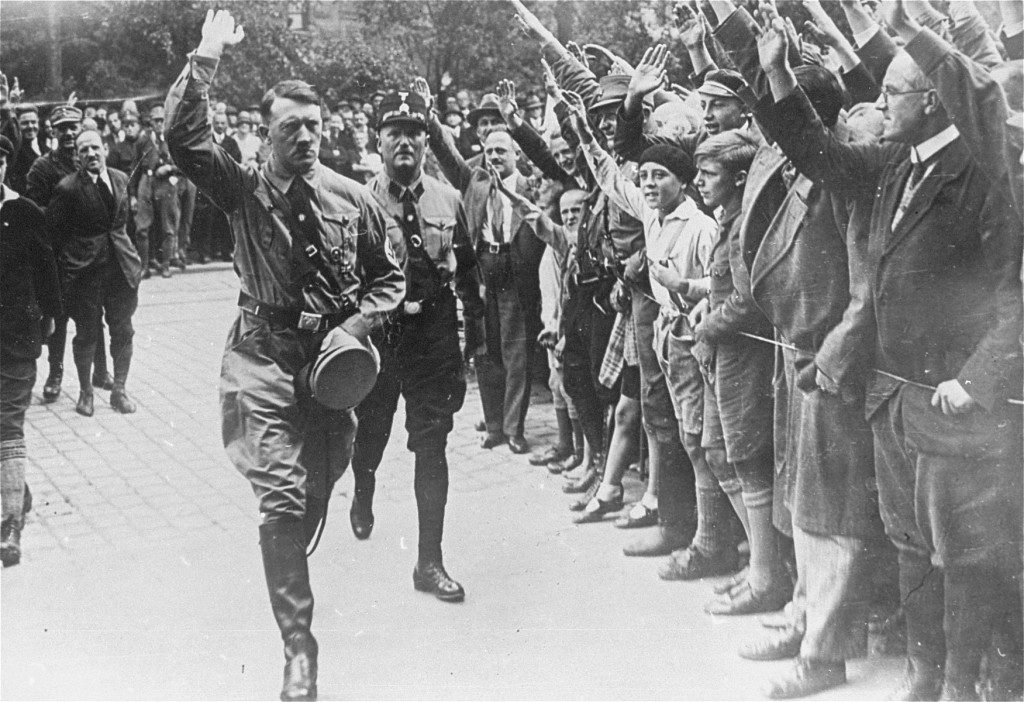

Sensing an unparalleled opportunity, the Nazis entered the campaign enthusiastically. In the public imagination, they were untainted with Weimar policies that were—they argued—the source of the increasing political deadlock, economic misery, and moral deterioration felt by Germans across the political spectrum. Modern technology (e.g. air travel, radio, mass rallies with technological bells and whistles, and deep engagement of the country’s youth) enhanced Nazi campaigning. Hitler himself, the first German politician to use air travel in a political campaign, blanketed the country to deliver his message of national renewal to a nation perceiving itself to be increasingly spiraling into an existential and lethal political, economic and cultural/moral crisis.

In the September 14, 1930 elections, the Nazi Party captured 18.3% of the vote, depending significantly on new voters, unemployed voters, and alienated voters deserting the middle class parties.

Critical Thinking Questions

The Nazi regime required the active help or cooperation of professionals working in diverse fields who in many instances were not convinced Nazis. How did Hitler and other Nazi leaders use their positions of power to put their radical ideas into practice?

What other societal factors and attitudes contributed to the rise of Hitler?

How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity?