Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Rise to Power, 1918–1933

Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. In the months that followed, the Nazis transformed Germany from a democracy into a dictatorship. Hitler and the Nazis’ rise to power was not inevitable. It was the result of many factors, including timing, circumstances, and sheer luck.

Key Facts

-

1

In the early 1920s, the Nazi Party was a small, radical, right-wing political movement that wanted to overthrow German democracy. Hitler and the Nazis tried and failed to seize power by force in November 1923.

-

2

In the mid-1920s, the Nazis changed their strategy. They began competing in elections to try to undermine German democracy from within. The Nazi Party started to gain significant numbers of votes in national elections in September 1930.

-

3

The Nazis used political violence, grassroots campaigning, propaganda, and political scheming to destabilize the Weimar Republic, win supporters, and take power.

Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power in Germany on January 30, 1933. That day, German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor. At the time, Germany was governed by a democratic republic known as the Weimar Republic.

The Weimar Republic had been established almost 15 years earlier, at the end of World War I (1914–1918). It replaced the German Empire (1871–1918), which collapsed at the end of the war in November 1918. The Weimar Republic was a parliamentary democracy. Its constitution guaranteed equality of all citizens before the law. It also guaranteed civil liberties such as freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of religion. Many Germans embraced the end of the German Empire and the founding of the new republic. However, others rejected the republic as illegitimate.

Hitler and the Nazis hated the Weimar Republic. They considered parliamentary democracy to be a weak form of government. They despised the Weimar Republic’s leaders for signing the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919. The Nazis were also antisemitic, meaning they hated Jewish people. They embraced antisemitic conspiracy theories about the end of World War I, the founding of the Weimar Republic, and communism. They wrongly blamed Jews for many of Germany’s postwar problems. The Nazis called for a strong, authoritarian Germany that was free of Jews.

In the early 1920s, the Nazi Party was a small, unpopular, and ineffective political movement. But by mid-1930, this had changed. By that time, the Great Depression had caused an economic and political crisis in Germany. The Nazis became increasingly popular by attacking the Weimar government as ineffective and promising to create a strong Germany. Over the next two and a half years, the Nazis ruthlessly exploited features of the Weimar Republic’s democratic system of government to gain power. This was possible because of three key factors:

- genuine popular support for Hitler and the Nazi Party among large numbers of Germans beginning in late 1929;

- the manipulation of the German democratic system of government by various political leaders; and

- backroom dealing by German President Paul von Hindenburg and a small number of right-wing, anti-democratic politicians in 1932 and early 1933.

1918–1924: The Nazi Party on the Anti-Democratic Political Fringe

The Weimar Republic was an unstable democracy during its first five years. In the aftermath of World War I, the new government faced both domestic and international crises. Like many European countries, Germany struggled with widespread hunger, disease, crime, and political extremism. Communist movements, inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, attracted some Germans and terrified many others. It was in this post-World War I context that the Nazi Party was founded in January 1919. At the time, it was officially known as the German Workers’ Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, DAP).

The Nazi Party’s Goals and Ideology

In the early 1920s, the Nazi Party was a small, radical, right-wing antisemitic movement. Adolf Hitler quickly became the party’s undisputed leader. As laid out in Hitler’s early speeches and the party platform (1920), the Nazis were antisemitic, ultranationalist, and anti-democratic. They were also anti-communist.

Hitler and the Nazi Party wanted to overthrow the Weimar Republic and install an authoritarian government. They sought to take over Germany by force. By the end of 1921, the party had a paramilitary unit, the SA (Sturmabteilung). The SA supported the party and helped fight its battles. The Nazi Party’s rhetoric and goals were so extreme that, in 1922, a number of German states banned the party as a threat to the republic.

The Beer Hall Putsch

On November 8–9, 1923, Hitler and other Nazi leaders tried to seize power in the German state of Bavaria. They planned to march on Berlin to overthrow the German government. At the time, the Nazi Party had about 55,000 members.

This attempted coup, known as the Beer Hall Putsch, quickly failed. Hitler was arrested, tried, and convicted of treason. The trial made Hitler famous, especially in right-wing, nationalist circles. In response to the coup attempt, Bavarian authorities banned and dissolved the Nazi Party, the SA, and Nazi newspapers.

1925–1929: The Nazis Try the “Legal” Path

During the months that Hitler was in prison, the political and economic situation in the Weimar Republic stabilized. The German economy grew stronger, the political system functioned, and art and culture flourished. This period (1924–1929) is often considered the golden era of Weimar.

When Hitler was released from prison in December 1924, he faced a new political and economic landscape. He realized it would not be possible for the Nazis to take control of Germany by force. Thus, Hitler resolved to change the Nazi Party’s political strategy. He decided that the Nazis would compete in parliamentary elections and attempt to win mass support. Hitler called this the path of “legality.”

We are going into parliament to arm ourselves with weapons from democracy's arsenal. We are becoming members of parliament in order to hamstring the Weimar way of thinking…. If democracy is stupid enough to give us free tickets and allowances for this disservice, that is its own business. We don't worry about it. We will use any legal means to revolutionize the current state of affairs.

—Joseph Goebbels, Nazi leader for Berlin

This decision was controversial within the anti-democratic Nazi movement. However, the Nazi Party had only changed its political strategy, not its philosophy. Hitler and the Nazis continued to disparage the Weimar Republic, condemn party politics, and demand an authoritarian state.

Building the Party’s Grassroots Infrastructure

In early 1925, the Bavarian government lifted the ban on the Nazi Party. Hitler worked to revive the movement and reunify it under his control. Nazi leaders made efforts to rebuild the party membership, which had declined after the Beer Hall Putsch. They also founded new Nazi paramilitary organizations. They established the SS (Schutzstaffel, Protection Squadron) in 1925 and the Hitler Youth in 1926.

In 1928, Nazi leaders created a centralized political organization that extended the Nazis’ reach to all of Germany. The new party structure corresponded with Germany’s electoral districts in order to facilitate election campaigning. The party’s sophisticated grassroots organization would eventually help bring Hitler to power in 1933.

Poor Electoral Outcomes for the Nazis, 1926–1928

Despite their efforts, the Nazi Party remained small and marginal in the mid- and late 1920s. Their radical antisemitism and anti-democratic messages did not appeal to many voters during this period of prosperity and stability. In state elections in 1926 and 1927, the Nazi Party received between 1.6 and 2.5 percent of the vote. On May 20, 1928, the Nazis competed in elections for the Reichstag (national parliament). They received only 2.6 percent of the vote. At the time, the Nazi Party had about 100,000 members.

As a result of the May 1928 elections, Social Democratic politician Hermann Müller became chancellor of Germany. He oversaw a grand coalition government, which included a number of political parties that supported the Weimar Republic.

Nazi Efforts to Win Over the Middle Classes, 1928–1929

The poor electoral showing encouraged the Nazi Party to shift tactics. Previously, the Nazis had tried to win over working-class voters. After the May 1928 election, however, they made increasing efforts to win over rural and middle-class voters. They sought to appeal to small business owners, artisans, clerks, farmers, and agricultural workers. The Nazis saw success relatively quickly, especially after the German economy began to struggle in early 1929.

Nazi Propaganda, Targeted Messaging, and Antisemitism

Hitler and other Nazi speakers carefully tailored their speeches and programs to their audiences. This allowed the Nazis to address local and regional concerns, both economic and ideological. The Nazis offered a utopian nationalist vision. They hoped this vision would appeal to a broad voter base and cut across social classes.

In 1928, Hitler and the Nazis began to downplay their most extreme antisemitic ideas. For example, they stopped mentioning their intention to exclude Jewish people from German citizenship.

Still, Germans knew that Hitler and the Nazis hated Jews. Nazi newspapers continued to attack Jews and spread antisemitic conspiracy theories. Germans often heard groups of Nazis sing antisemitic songs and yell antisemitic chants. For instance, the Nazis chanted phrases such as “Jews out of Germany” and “beat the Jews to death.” Germans also saw Nazis boycotting and vandalizing Jewish-owned businesses. In addition, they witnessed them beating up and attacking Jewish people.

1930: Germany’s Democracy in Crisis and the Nazi Breakthrough

The golden age of the Weimar Republic ended in late 1929, when the Great Depression hit Germany. Unemployment rose quickly. Many Germans felt that the government was unable to manage the crisis. In these circumstances, the Nazi Party started to win more votes.

Political Deadlock in Germany

The economic crisis soon caused political deadlock in Germany. The parties in power could not agree on how to respond to the worsening economic situation. In March 1930, Chancellor Müller and his entire government resigned over a debate about how to handle Germany’s straining unemployment insurance program.

In place of Müller (a Social Democrat), German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Heinrich Brüning as chancellor. Brüning was a Center Party politician. The conservative Hindenburg wanted a right-wing government that aligned with his values. On Hindenburg’s orders, Brüning’s government excluded the center-left Social Democrats. This change meant that Chancellor Brüning did not have a parliamentary majority supporting him.

Brüning oversaw the first in a series of presidential cabinets (Präsidialkabinette). These were governments that did not have a parliamentary majority. They were primarily based on President Hindenburg’s support.

Using Emergency Decrees to Govern

In July 1930, Hindenburg and Brüning issued an emergency decree to enact a deflationary budget despite parliament’s opposition. They used Article 48 of the German constitution. Article 48 permitted the German president to take measures bypassing parliamentary consent in cases of national emergency. Parliament, in line with its constitutional right, voted to force Hindenburg to rescind the emergency decree. In response, Hindenburg and Brüning dissolved parliament and called new special parliamentary elections.

Nazi Success in the Election of September 1930

The special national parliamentary elections were scheduled for September 14, 1930. Hitler and the Nazis campaigned aggressively. Their message focused on condemning the Weimar Republic as weak and ineffective.

The Nazi Party leader in Berlin, Joseph Goebbels, coordinated the nationwide campaign propaganda, which included posters, marches, and rallies. In the month before the election, the Nazis held tens of thousands of events across Germany. In large cities, Hitler spoke at mass events to thousands of people. Some of these political events turned violent as Nazis brawled with their political opponents, especially the Communists.

In September 1930, the Nazi Party won 18 percent of the vote. It became the second-largest political party in parliament. Even though the Nazis had been gaining votes for more than a year, the election results surprised many Germans and sent shockwaves throughout Germany. Hitler was suddenly an important player in German politics. Chancellor Brüning, however, refused to enter into a coalition government with the Nazi Party.

1931: The Crisis of Democracy Deepens

In 1931, Germany’s economic, social, and political situation continued to deteriorate. The number of unemployed people increased. Banks collapsed. Germany’s political system further strained under the pressure. In addition, the strength of the Communist Party alarmed many Germans.

Even though Hitler had publicly promised to follow a path of legality, his end goal was to destroy German democracy. The Nazis found ways to disrupt and destabilize the country while simultaneously promising that they alone could bring stability and restore order.

Nazi Party Disruption and Obstruction in Parliament

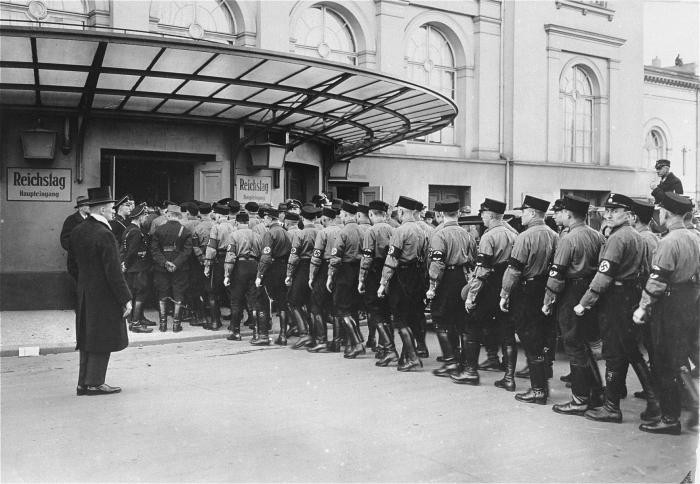

In parliament, Nazi deputies were deliberately disruptive and rowdy. They refused to support any of the Brüning government’s measures and regularly called votes of no-confidence. They derailed parliamentary sessions by introducing irrelevant points of order.

Brüning attempted to work around this situation. With Hindenburg’s support, he repeatedly resorted to Article 48 to issue emergency decrees. He enacted economic measures that did little to relieve unemployment or help those in poverty. As a result, the Communists began referring to him as the “hunger chancellor” (Hungerkanzler). Brüning also sent parliament into long periods of recess.

Undermining Public Order With Political Violence

By 1931, political violence on Germany’s streets had become unmanageable. This was in large part because of the increase in paramilitary groups affiliated with parties from across the political spectrum. The Nazi Party’s paramilitary, the SA, was especially radical and violent. SA men often abused Jews and smashed the windows of Jewish-owned businesses. They regularly brawled with and even killed their political opponents, especially Communists. In turn, scores of Nazis were killed by opposing groups. The German government and police forces failed to contain the political violence. This further undermined many Germans’ faith in the Weimar Republic.

Government Efforts to Stop the Disruption

National and state governments attempted to stop the chaos created by the Nazis and the Communists. In 1931, the Brüning government enacted four emergency decrees related to political turmoil. These decrees allowed government authorities to infringe on freedoms of speech and assembly in the name of public safety and order. For example, they could ban the wearing of political uniforms or badges; confiscate newspapers; and prohibit certain gatherings.

None of these measures were able to stop the growth of the Nazi movement. By the end of 1931, the Nazi Party had 806,294 members. The party also performed well in local and state elections that year.

1932: A Year of Elections and Political Scheming

In 1932, there were five major elections in Germany. From late February through November, political rallies, demonstrations, and marches dominated German life. In campaigns, the Nazis tried to create a feeling that they were the future and that their victory was inevitable. To do so, they used new technologies, like sound and airplanes, to campaign in unexpected ways. They made and distributed sound recordings of campaign speeches and played sound films. Hitler attracted media attention as he traveled throughout Germany by airplane. He visited multiple cities a day, giving short speeches to crowds of tens of thousands.

In addition to campaigning, Hitler often negotiated behind the scenes with a small group of right-wing politicians in the hopes of entering the government. These politicians included:

- President Hindenburg and his son Oskar;

- Hindenburg's chief of staff Otto Meissner;

- General Kurt von Schleicher;

- Alfred Hugenberg (the leader of the right-wing German National People’s Party, or DNVP); and

- Franz von Papen.

Like Hitler, these men opposed the Weimar Republic, hated the Social Democrats, and feared communism. They hoped to use the Nazis’ popularity for their own purposes. They were willing to ignore any parts of Nazism and Hitler’s personality that they found distasteful. These men partnered with Hitler and the Nazis to take advantage of the crisis in Germany. Together, they undermined and ultimately destroyed German democracy.

The choices of this small group explain how and why Hitler came to power when he did.

Hitler Runs for President, March–April 1932

In 1932, President Hindenburg’s first seven-year term in office ended. New presidential elections were scheduled for March 13. Hitler decided to challenge Hindenburg, who had reluctantly decided to run for re-election. Hindenburg had the support of many political parties from across the political spectrum.

Hitler, who was 42, presented himself as the only hope for Germany’s future. He emphasized that the Nazi movement was the party of youth. In speeches, Hitler often referred to the 84-year-old Hindenburg as “old man.” He also consistently attacked the Social Democrats (who had decided to support Hindenburg) and the Weimar Republic. On March 13, Hindenburg won just under 50 percent of the vote, narrowly missing an outright majority. Hitler had 30 percent of the vote. In the run-off election on April 10, Hindenburg won the presidency with 53 percent of the vote. Hitler increased his vote share to just under 37 percent.

Nazi Success in State Elections in Prussia, April 1932

On April 24, state parliamentary elections were held in Prussia and several other German states. The Prussian election was especially important. Prussia was by far the largest German state. It was home to approximately 38 million people. About 60 percent of the German population lived in Prussia.

The Nazis continued to campaign at a feverish pace and built on the momentum from the presidential campaign. The Nazi Party won 36 percent of the vote in Prussia. Despite this significant showing, the Nazis did not succeed in taking over or joining the Prussian government. Instead, the center-left government coalition remained in power temporarily. They were a caretaker government without a majority in the Prussian parliament.

Chancellor Brüning’s Dismissal

In late May 1932, Hindenburg dismissed Chancellor Brüning. This dismissal was the result of Hindenburg’s frustration with the chancellor and political scheming in Hindenburg's inner circle. In Brüning’s place, Hindenburg appointed Franz von Papen. Papen was more right-wing and conservative than Brüning. He better suited Hindenburg’s and his advisors’ goals.

The Nazis supported Papen’s appointment in exchange for two concessions. First, they wanted the government to lift the national ban on the SA. Brüning’s government had imposed this ban in April. Second, the Nazis demanded new special parliamentary elections. Papen and Hindenburg agreed. The ban on the SA was lifted, parliament was dissolved, and new elections were scheduled for July 31. Given their showing in the Prussian state elections, it was almost certain that the Nazis would do well.

In hindsight, Hindenburg’s decision to dismiss Brüning and call new elections was one of the most consequential decisions of this period. It helped enable the Nazi rise to power. The special elections deepened political tensions and set the stage for the Nazis to become the most popular political party in Germany.

A Blow against Democracy: Chancellor Franz von Papen and the Coup in Prussia

After the ban on the SA was lifted, political violence continued to escalate on the streets of Germany. Papen used one bloody incident started by the SA in the Prussian city of Altona as an excuse to seize control of the Prussian state government. Hindenburg and Papen asserted that the political violence constituted an emergency. They used Article 48 to take over Prussia. Papen became the Reich Commissioner (Reichskommissar) for Prussia. He removed leftist and centrist politicians from their positions.

Papen’s authoritarian power grab over Prussia weakened the pluralism of the Weimar Republic’s federal system. It opened the way to the abolishment of democracy and the creation of a more authoritarian order in Germany. This would have important consequences six months later, after Hitler was appointed chancellor.

The July 1932 National Parliamentary Election

In the lead-up to the July 1932 elections, the Nazis once again campaigned with fervor, building on earlier campaign themes. One of their slogans was “Germany awaken! Give Adolf Hitler power!” The Nazis condemned the Communist Party and the Weimar Republic’s government. They spread their message at mass rallies, on posters, and in newspapers and leaflets. Despite their earlier bargain, the Nazis also viciously attacked Papen’s cabinet.

The Nazi Party won 37 percent of the vote in the election on July 31, 1932. It became the largest political party in parliament. Based on these results, Hitler demanded that he be appointed chancellor. President Hindenburg refused. The SA had been increasingly violent in the aftermath of the election. Their actions concerned Hindenburg and his advisors. Hitler was humiliated and angry. He declined to join the government in any other role.

A Nazi Dominated Parliament

In the aftermath of the July election, Chancellor Papen faced a hostile parliament. The Nazis and the Communists controlled more than half of the seats. In September 1932, Papen dissolved parliament, with Hindenburg’s blessing. He did so in order to dodge a parliamentary vote of no-confidence in his government. Another special parliamentary election loomed in November.

The Nazi Party Loses Votes, November 1932 Elections

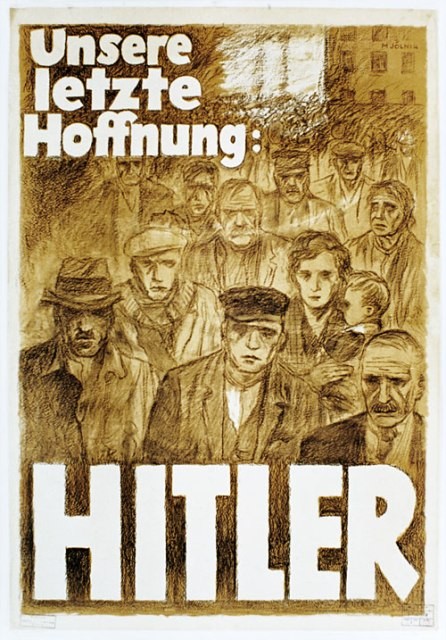

By the November 1932 elections, Germans were exhausted by the constant campaigning. Even the Nazis were fatigued and pessimistic. But Hitler continued to campaign doggedly. He attacked Papen as a reactionary and condemned his pro-business economic measures. One campaign poster called Hitler “our last hope.”

The election on November 6, 1932, was a major setback for the Nazi Party. Voter turnout was lower. The Nazis won 33 percent of the vote. This was 4 percent less than in July. The Nazi aura of dynamism and invincibility was broken.

This election seemed to signal to Germans and international observers the collapse of the Nazi Party. However, the results did not actually change the balance of power. The Nazi Party was still the largest party in parliament, and Hitler still refused to compromise. He insisted on being appointed chancellor on his terms. The stalemate continued. None of the political parties could agree on forming a governing coalition.

Backroom Negotiations

In early December, President Hindenburg appointed General Kurt von Schleicher as chancellor. Schleicher was his longtime ally. However, he quickly lost Hindenburg’s trust. He also failed to find a workable solution to the problem of governing.

In late December 1932 and throughout January 1933, Papen schemed to bring down Chancellor Schleicher’s government. He pressured Hindenburg to appoint Hitler chancellor. Initially, the president continued to resist. So, Papen recruited Hindenburg’s closest confidantes and other conservative, anti-democratic politicians to help persuade him. In late January, this group finally convinced Hindenburg. Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor on January 30. Hindenburg and his advisors, chiefly Papen, felt confident that they could control Hitler and limit his power.

1933: Hitler Comes to Power

Events moved quickly in 1933. Within the month of January, Hitler went from being an outsider to being appointed chancellor of Germany. As chancellor, he quickly set out to fulfill his campaign promises and transform Germany from a democracy into a dictatorship.

Hitler’s First Cabinet

Hitler led a right-wing coalition government which included the Nazi Party and the German National People’s Party (DNVP). Franz von Papen served as vice chancellor. In addition to the chancellorship, Hitler initially demanded that just two cabinet positions be filled with Nazi politicians. Wilhelm Frick served as Minister of the Interior. This role was in charge of security and policing. Hermann Göring became a minister without a portfolio. All other cabinet positions were held by non-Nazis.

Following Hitler’s demands, Hindenburg dissolved parliament and called new elections. This was the third parliamentary election in less than a year.

The First Steps From Democracy to Dictatorship

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was the chancellor of Germany, but he was not yet a dictator. The democratic Weimar Republic’s constitution was still in effect. Hitler and other Nazi leaders, however, were prepared to take advantage of every opportunity and legal loophole to transform Germany from a democracy into a dictatorship.

In late February, the German parliament building burned down in an arson attack. The Nazis used this fire as an opportunity to seize more power. Hitler convinced Hindenburg to use Article 48 to enact the Reichstag Fire Decree. The first article in this emergency measure suspended civil liberties and due process indefinitely. The second article allowed the national government to take over state governments, as Papen had once done in Prussia. Based on this decree, the Nazis began to terrorize political opponents (including members of parliament); expand police powers; and create concentration camps.

The Last Multi-Party Election, March 5, 1933

The March 1933 parliamentary election took place in an atmosphere of Nazi intimidation and terror against their leftist political opponents. Before the election, Nazis arrested most Communist Party leaders, including party chairman Ernst Thälmann. The government used the Reichstag Fire Decree to dramatically limit the ability of the Social Democrats and Communists to campaign.

In the elections, the Nazi Party won almost 44 percent of the vote. Their conservative coalition partners won 8 percent. Combined, this gave Hitler’s government more than 50 percent support in parliament. But, even amid oppression and terror, the Social Democrats earned 18 percent, and the Communists received 12 percent. The March 1933 election was the last multi-party election in Germany until after World War II.

The Enabling Act, March 23, 1933

On March 23, the newly elected parliament passed the Enabling Act. This law gave Chancellor Hitler the power to enact legislation without parliament. Under this law, Hitler was even able to enact legislation that violated the constitution.

To guarantee the passage of this law, Hitler and the Nazi Party intimidated, persecuted, and/or arrested many elected politicians. The Enabling Act only passed because the Hitler government suppressed and intimidated other political parties and manipulated parliamentary rules.

Hitler used the powers granted to him by the Enabling Act to further transform Germany. On April 7, the Nazi regime enacted the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service. This law allowed the government to fire government employees for political reasons or because they were Jewish. Numerous other discriminatory and dictatorial measures soon followed.

In July 1933, the Nazi Party became the only legal political party in Germany.

1934: Hitler Becomes Dictator

The Nazis’ power grab was complete in August 1934, when President Paul von Hindenburg died. A new law combined the offices of president and chancellor and granted Hitler the powers of both offices. Hitler became the absolute dictator of Germany. There were no longer any legal or constitutional limits to his authority.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

Joseph Goebbels, “What do we want with the Reichstag?” [“Was wollen wir im Reichstag?”] in his newspaper Der Angriff [The Attack], April 30, 1928.

-

Footnote reference2.

An array of political parties competed in national, state, and local elections in the Weimar Republic. National parliamentary elections were scheduled every four years and there were also provisions for special elections. In the history of the republic, no political party ever won an absolute majority of the vote in national parliamentary elections. Multiple parties partnered together to support a chancellor and form coalition governments.

-

Footnote reference3.

The constitution established Germany as a federal republic. This meant that it was made up of constituent states that had their own governments and republican constitutions. The largest German states were Prussia (which accounted for slightly more than 60 percent of the German population) and Bavaria (more than 11 percent). The federal government shared power with the states.

Critical Thinking Questions

How did the German constitution contribute to the Nazi rise to power?

What pressures and motivations led some officials to arrange for the appointment of Hitler as chancellor?

What do you consider to be the ideal priorities of government officials to uphold, particularly in times of crisis?

How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity in the world?