Culture in the Third Reich: Disseminating the Nazi Worldview

National Socialism represented much more than a political movement. Nazi leaders who came to power in January 1933 wanted to gain political authority, to revise the Versailles Treaty, and to regain and expand upon those lands lost after a humiliating defeat in World War I. But beyond those goals, they also wanted to change the cultural landscape. They wanted to return the country to traditional “German” and “Nordic” values, to remove or limit Jewish, “foreign,” and “degenerate” influences, and to shape a racial community (Volksgemeinschaft) which aligned with Nazi ideals.

These ideals were at times contradictory. National Socialism was at once modern and anti-modern. It was dynamic and utopian, and yet often hearkened back to an idyllic and romanticized German past. In other areas, Nazi cultural principles were consistent. They stressed family, race, and Volk as the highest representations of German values. They rejected materialism, cosmopolitanism, and “bourgeois intellectualism,” instead promoting the “German” virtues of loyalty, struggle, self-sacrifice, and discipline. Nazi cultural values also placed great importance on Germans' harmony with their native soil (Heimat) and with nature, and emphasized the elevation of the Volk and nation above its individual members.

Role of Culture in Nazi Germany

In Nazi Germany, a chief role of culture was to disseminate the Nazi world view. One of the first tasks Nazi leaders undertook upon their ascension to power in early 1933 was a synchronization (Gleichschaltung) of all professional and social organizations with Nazi ideology and policy. The arts and cultural organizations were not exempt from this effort. Joseph Goebbels, the Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, immediately strove to bring the artistic and cultural communities in line with Nazi goals. The government purged cultural organizations of Jews and others alleged to be politically or artistically suspect.

On May 10, 1933, Nazi university students organized nationwide book burning ceremonies in which they threw into the flames the works of such “un-German” writers as Bertolt Brecht, Thomas Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, and the texts of Jewish authors, including such famous German writers as Franz Werfel, Lion Feuchtwanger, and Heinrich Heine.

Beginning in September 1933, a new Reich Culture Chamber (Reichskulturkammer)—an umbrella organization composed of the Reich Film, Music, Theater, Press, Literary, Fine Arts, and Radio Chambers—moved to supervise and regulate all facets of German culture.

The new Nazi aesthetic embraced the genre of classical realism. The visual arts and other modes of “high” culture employed this form to glorify peasant life, family and community, and heroism on the battlefield. They promoted such “German virtues” as industry, self-sacrifice, and “Aryan” racial purity. In Nazi Germany, art was not just “for art's sake,” but had a calculated propagandistic undercurrent. It stood in stark contrast to the trends of modern art in the 1920s and 1930s, much of which employed abstract, expressionist, or surrealist tenets. In July 1937 a “Great German Art Exhibition” displaying the cultural bent of National Socialist artistic taste premiered in the House of German Art in Munich.

A nearby exhibition hall presented, in contrast, an “Exhibition of Degenerate Art” (Entartete Kunst) in order to demonstrate to the German public the “demoralizing” and “corruptive” influences of modern art. Many of the artists featured in the Degenerate Art exhibition, such as Max Ernst, Franz Marc, Marc Chagall, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky, number today among the great artists of the twentieth century. In the same year Goebbels ordered the confiscation of thousands of “degenerate” artworks from museums and collections throughout Germany. Many of these pieces were destroyed or sold at public auction.

Architecture

In architecture, artists like Paul Troost and Albert Speer constructed monumental edifices in a sterile classical form meant to convey the “enduring grandeur” of the National Socialist movement. In literature, Nazi cultural authorities promoted the works of writers such as Adolf Bartels and Hitler Youth poet Hans Baumann. Literature glorifying the peasant culture as bedrock of the German community and historical novels bolstering the centrality of the Volk figured as preferred works of fiction, as did war narratives which worked to prepare the population for, or to sustain it in, an era of conflict. Censorship represented the other side of this equation: the Literary Chamber quickly established "black lists" to facilitate the removal of "unacceptable" books from public libraries.

Cinema

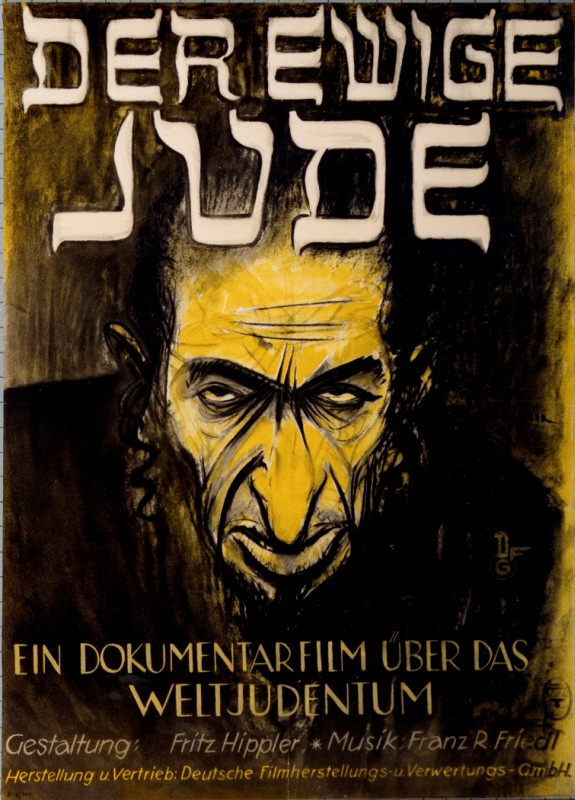

The Nazi “cultivation of art” also extended to the modern field of cinema. Heavily subsidized by the state, the motion picture industry proved an important propaganda tool. Films such as Leni Riefenstahl's pioneering Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will) and Der Hitlerjunge Quex (Hitler Youth Member Que”), glorified the Nazi party and its auxiliary organizations. Other films, such as Ich klage an [I Accuse], aimed to gain the public's tacit acceptance of the still clandestine Euthanasia Program, while Jud Süss and Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) underscored the antisemitic elements of Nazi ideology.

Theatre

Theatre companies followed the example of German cinema, staging National Socialist dramas as well as traditional and classical performances of the plays of writers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Friedrich Christoph von Schiller.

Music

In music, the Nazi cultural authorities promoted the works of such giants of the German musical pantheon as Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Anton Bruckner, and Richard Wagner, while banning classical works by "non-Aryans," such as Felix Mendelssohn and Gustav Mahler, and performances of jazz music and Swing, associated in the Nazi mind with African-American culture.

Adolf Hitler was himself a longtime devotee of the operas of Richard Wagner—an artist long associated with antisemitism and the völkisch tradition from which the Nazis drew much of their ideology. He regularly attended the annual Bayreuth Festivals held in the Wagner's honor. But “Nazi” music did not confine itself solely to “high” culture: songs like Das Horst-Wessel-Lied (The Horst Wessel Song) and Deutschland, Erwache! (Germany, Awake) numbered among many songs and marches which Nazi activists circulated in order to encourage commitment to the Nazi party and its ideological tenets.

Total Culture

The efforts of Nazi authorities to regulate, direct, and censor German arts and letters corresponded to what the late German historian George Mosse called an effort “toward a total culture.” That effort also reached down to those lower levels of culture which punctuated the everyday lives of ordinary Germans. The Nazi leadership, which hoped to dominate Germany through political power and terror, but also by winning the “hearts and minds” of the population, utilized this coordination of culture, high and low, to influence at the most basic level the lives and actions of its citizens.

Critical Thinking Questions

What are the positives and negatives of synchronizing culture with national goals and ideology?

What methods do governments use to achieve this goal? What alternatives might exist for citizens and artists?