David Bayer

“We were innocent people…we believed in God, we would pray every Saturday…Then, the Germans start coming into our home, put a Star of David on our door…” Listen to David Bayer describe the arrival of the Germans in his hometown in September 1939. Learn about some of his experiences, actions, and the choices he was forced to make during the Holocaust.

Audio

Transcript

David Bayer:

I was 16 years old when the Germans came into my town, and before that I was a happy guy, with a nice family. My father had a shoe factory, and we had about 15, 16 people working for us. My sister, she was 18 years old, my brother 12 and my little sister 8 years old. My parents were, my father was 42 and my mother was 41, and we had a nice home and a garden, and everything else, and I was going to school and playing soccer, riding a bike, having a nice young life.

When the Germans came in, everything changed. We lived in an area with a Christian section, and close to a church, because my father needed more space for the factory, so that’s why we lived over there, with our backyard, and our shop.

The population was a lot of shoe factories, a lot of tailors, a lot of watchmakers, and all kind of craftsmen. And the area was farm, the area near where my hometown, all the farmers came once a week to deal with the Jewish people.

We were very friendly; we had no problems. And there was a colony of ethnic Germans living not far, and we were very friendly with them. And we had no problem. We lived our lives and they lived theirs, and that’s it. But the Germans changed the whole situation.

Bill Benson:

And once they came, things changed dramatically, right?

David Bayer:

Everything changed dramatically. Like, when the Germans came in, we had to run away. We run to the forest. Everybody run out because they bombarded the town, and there was a lot of shooting. And when we came back, we find Germans ransacking our home, taking everything out, whatever they could–even the dishes.

And they were looking for shoes, for leather, for machinery, whatever they could take. We came back, after a few days [of] being in the forest, and there were Germans in our home. And my mother cried because one German pulled down a box of Passover dishes and broke it, from a shelf, broke everything, and whatever didn’t break, he took it.

Bill Benson:

And those dishes had been in the family–

David Bayer:

They’d been there for hundreds of years.

Bill Benson:

Hundreds of years.

David Bayer:

You know, porcelain and silver dishes. Well, the Germans left with laughter; they were making fun of us. One German even asked my father, “How come nobody likes Jews?”

And I was standing next to my father. My father said, “Because we don’t hit back.”

He made a gesture like, and I got so scared, I thought my father was going to hit that German. But [like] he said, we don’t hit back. And that’s why they don’t like us. And we never did hit back. My grandfather used to tell me if I had a fight in school: just don’t do it, put the other cheek. That’s what they always tell you.

And this is the problem we had. We were innocent people; we didn’t do nothing. We were only religious, we believed in God, we would pray every Saturday, you know, we had a good religious life. Then, the Germans start coming into our home, put a Star of David on our door, because we lived in a Christian area, they wanted to know we were living there.

And then one day they come in, one German came in, and he took me out–there were a few of them, but the one grabbed me–he pulled me out of the house to do some work for them. And there were a bunch of German soldiers standing there behind a church, and they wanted me to take out a battery from under the truck.

I never had a truck; I never saw a car in my town. We had horses and wagons. And I didn’t know how to do it. My hands were bleeding; it was cold already, there was snow on the ground, and I had to lie down in the mud to take the battery out. And they were standing and laughing, taking pictures.

Finally I got the battery out, and the acid spilled on me and burned all of my clothes, to the skin. I was crying; I was yelling and crying. And they were taking pictures and laughing. The humiliation was–I could have died there and I would have been happier.

Finally, I begged them, I said, “Let me go home. I will come back; I will change my clothes.” They didn’t let me go. So when it got dark they told me to go; no food, no nothing. My mother was home and crying, waiting for me.

Biography

David Bayer was born on September 27, 1922, to Manes and Sarah Bayer in Kozienice, Poland. Manes owned a shoe factory which supplied stores throughout Poland, and Sarah managed the household and helped in the factory. The second of four children in an observant Jewish family, David spent his days going to school, playing sports, and working in his father’s factory.

The Germans captured Kozienice on September 9, 1939, eight days after they invaded Poland. During the bombardment, the Bayers hid in a nearby forest. When they returned, they found that most of their possessions—including Sarah’s heirloom Passover dishes—had been destroyed or taken by the German army. The Nazis began to implement antisemitic policies targeting Polish Jews. For example, they confiscated Jewish-owned businesses, and established a curfew. Manes’ factory was seized, and David was arrested for standing in a bread line after curfew had begun. His older sister Rose bribed a guard and secured his release.

In 1942, the Bayers were forced into the Kozienice ghetto. David ended up working as a house boy and translator for a Gestapo officer. He was then put to work on an irrigation canal project. He was at work on September 27, 1942, the day the Kozienice ghetto was liquidated. That day, David's 20th birthday, the majority of the ghetto’s inhabitants (including the Bayer family) were deported to Treblinka killing center, located in German-occupied Poland, where they were killed. David was smuggled back into Kozienice several days later and worked with a handful of remaining Jews to clean up the ghetto.

In December 1942, the Germans deported the approximately thirty-five Jews left in Kozienice to other nearby ghettos. David was eventually sent to the Pionki labor camp where he was put to work in a factory that manufactured gunpowder. There, David was injured in an accidental explosion that burned his face, hands, and feet. In 1944, the Germans sent the prisoners from Pionki to Auschwitz-Birkenau. David was tattooed with the prisoner number "B74." He was transferred to Neu-Dachs, a subcamp of Auschwitz, where he was forced to work in the Jaworzno coal mines. In January 1945, as the Red Army approached, the Nazis forced the prisoners to evacuate Neu-Dachs on foot. Many prisoners died of cold and starvation on this harrowing death march. After a brief stay at Blechhammer, another subcamp of Auschwitz, David escaped into the forest where Soviet soldiers liberated him. He was 23 years old and weighed only 70 pounds.

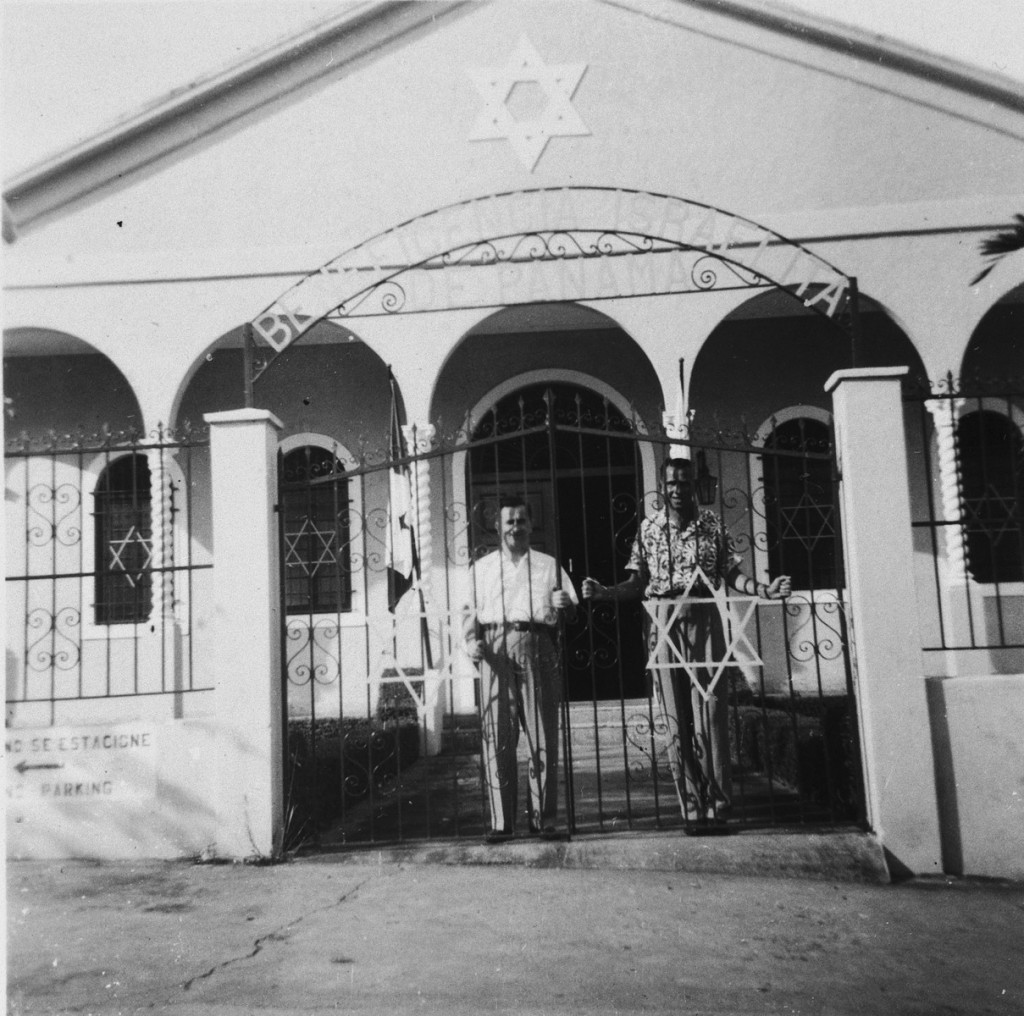

After his liberation, David made his way to the Foehrenwald displaced persons camp in the American sector of Allied-occupied Germany. In 1947, he first moved to Panama then to Palestine to fight in Israel’s War for Independence (1948). After the war, David returned to Panama and lived there until 1955 when he immigrated to the United States. He settled in the Washington, DC area and owned a liquor store until 1992. David married Adele Abramowitz in 1958 and had two children. David volunteered at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.