George Kadish

George Kadish (1910-1997) secretly documented life in the Kovno ghetto in Lithuania. The results constitute one of the most significant photographic records of ghetto life during the Holocaust era.

Key Facts

-

1

Kadish taught science at a Hebrew high school in Kovno before the war.

-

2

The first violent attacks against Kovno’s Jews in 1941 moved Kadish, an avid amateur photographer, to document their ordeals.

-

3

At great risk he secretly photographed ghetto life, sometimes even snapping pictures with a hidden camera through the buttonhole of his overcoat.

Before World War II

George Kadish was born Zvi (Hirsh) Kadushin in Raseiniai, Lithuania, in 1910. After attending the local Hebrew school, he moved with his family to Kovno. At the Aleksotas University, located in one of Kovno's suburbs, he studied engineering in preparation for a teaching career and joined the rightist Zionist movement called Betar. In the years before the war, he taught mathematics, science, and electronics at a local Hebrew high school.

His avocational interests, however, would have the most significant impact on his and others' lives. He started developing his interests in photography and began building his own cameras, including one designed for use on his trouser belt.

In the Kovno Ghetto

The Kovno ghetto had two parts, called the "small" and "large" ghetto, separated by Paneriu Street. Each ghetto was enclosed by barbed wire and closely guarded. Both were overcrowded, with each person allocated less than ten square feet of living space. The Germans continually reduced the ghetto's size, forcing Jews to relocate several times. The Germans destroyed the small ghetto on October 4, 1941, and killed almost all of its inhabitants at the Ninth Fort. Later that same month, on October 29, 1941, the Germans staged what became known as the "Great Action." In a single day, they shot 9,200 Jews at the Ninth Fort.

Kadish took every opportunity possible to document day-to-day life in the Kovno ghetto and, after his escape in 1944, the ghetto’s final days. The results constitute one of the most significant photographic records of ghetto life during the Holocaust era. Photographing life in the Kovno ghetto was an extremely risky venture. The Germans strictly prohibited it, and as with all defiant acts, they did not hesitate to murder offenders.

Acquiring and developing film secretly outside the ghetto were just as perilous as using hidden cameras inside. Kadish received orders to work as an engineer repairing x-ray machines for the German occupation forces in the city of Kovno. Once in the city, he discovered opportunities to barter for film and other necessary supplies. He developed his negatives at the German military hospital, using the same chemicals he used to develop x-ray film, and succeeded in smuggling them out in sets of crutches.

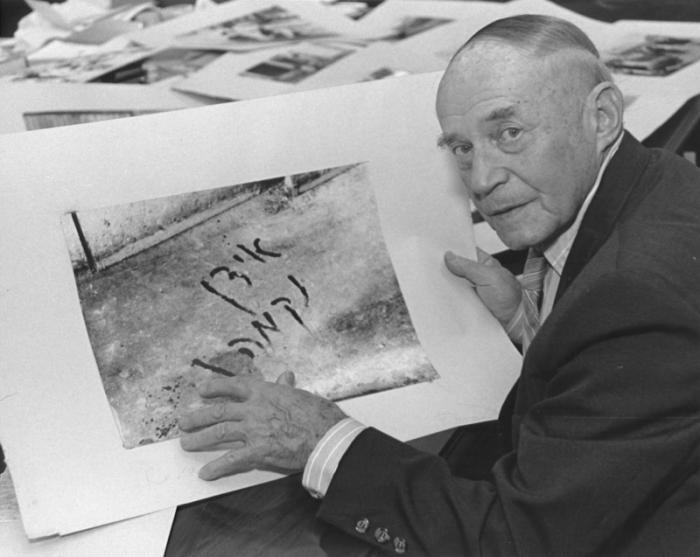

The subjects of Kadish’s photographic portraits were varied, but he seemed especially interested in capturing the reality of the ghetto’s daily life. In June 1941, witnessing the brutality of the initial pogroms, he photographed the Yiddish word Nekoma (“Revenge”) found scrawled in blood on the door of a murdered Jew’s apartment.

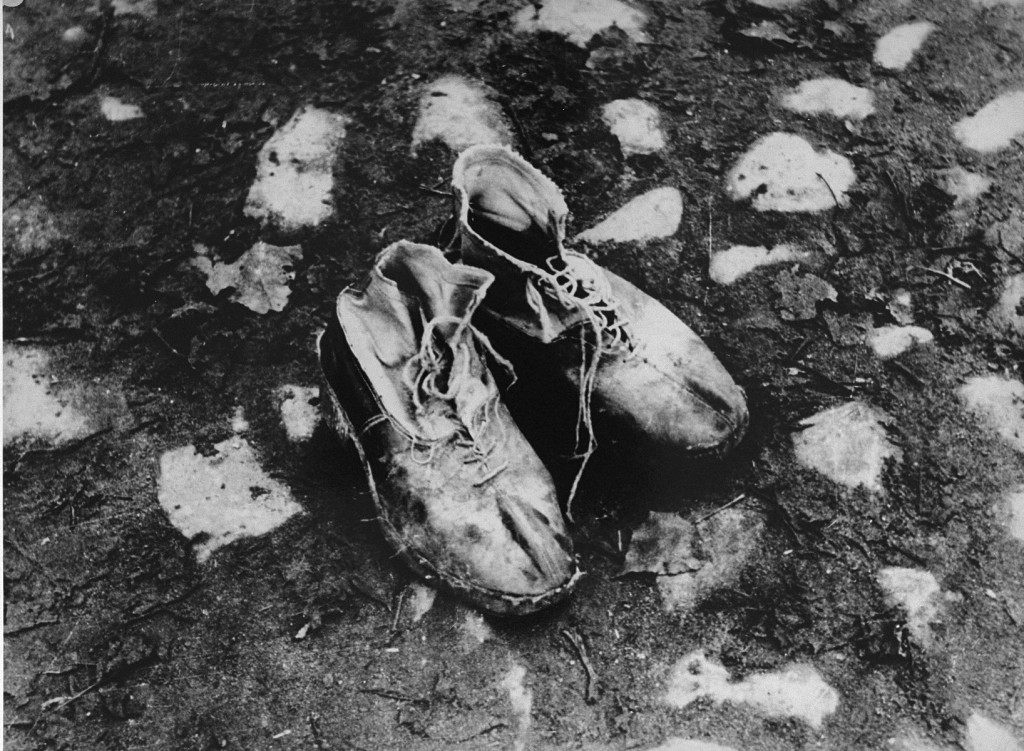

Camera in hand, or whenever necessary, placed to record subjects through a buttonhole of his overcoat, he photographed Jews humiliated and tormented by Lithuanian and German guards in search for smuggled food, Jews dragging their belongings from one place to another on sleds or carts, Jews concentrated in forced work brigades, and so forth. Kadish also recorded the new regimen of regulated daily activities at the Ältestenrat’s (as the Jewish council in Kovno was known) food gardens and in schools, orphanages, and workshops. In addition to depicting the severe conditions of ghetto life, he had an insider’s eye for portraiture, the desolation of deserted streets, and the intimacy of informal, improvised gatherings.

Among Kadish’s last photographs from inside the ghetto are those recording the deportation of ghetto prisoners to work camps in Estonia. In July 1944, after escaping from the ghetto, across the river, he photographed the ghetto’s liquidation. Once the Germans fled, he returned to photograph the ghetto in ruins and the small groups who had survived the final days in hiding.

Saving the Collection

Kadish recognized early on the danger of losing his precious collection. He enlisted the assistance of Yehuda Zupowitz, a high-ranking officer in the ghetto’s Jewish police, to help hide his negatives and prints. Zupowitz never revealed his knowledge of Kadish’s work or the location of his collection, even during the “Police Action” of March 27, 1944, when Zupowitz was tortured and killed at the Ninth Fort prison. Kadish retrieved his collection of photographic negatives upon his return to the destroyed ghetto.

After Germany’s surrender on May 8, 1945, Kadish left Lithuania for Germany with his extraordinary documentary trove. In the American zone of occupied Germany, he mounted exhibitions of his photographs for survivors residing in displaced persons camps. Since then, several museums, including New York’s Jewish Museum, have formally exhibited his work.

Critical Thinking Questions

How is documentation a form of resistance? Investigate other examples of documenting oppression throughout history.

What pressures and motivations may have influenced Kadish's decisions and actions? Are these factors unique to this history or universal?

How can societies, communities, and individuals reinforce and strengthen the willingness to document and to resist?