Hidden Children: Quest for Family

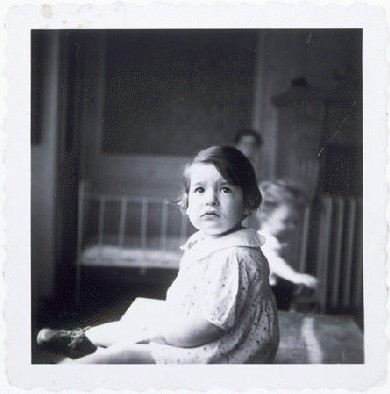

During the Holocaust, some children went into hiding to escape Nazi persecution. With identities disguised, and often physically concealed from the outside world, these youngsters faced constant fear, dilemmas, and danger. Following the war, many Jewish parents spent months or years searching for the children they had sent into hiding.

When the war ended in 1945, the surviving remnant of Europe's Jews immediately began the difficult and painful search for family members. Parents sought out the children they had placed in convents, orphanages, or with foster families. Local Jewish committees in Europe tried to register the living and account for the dead. Tracing services set up by the International Red Cross and Jewish relief organizations aided the searches, but often the quests were protracted because the Nazis, the war, and the mass relocations of populations in central and eastern Europe had displaced millions of people.

The quest for family was much more than a search for relatives. It often involved some traumatic soul searching for children to rediscover their true identity. Those who had been infants when they were placed into hiding had no recollection of their biological parents or knowledge of their Jewish origins. The only family that most had known was that of their rescuers. Consequently, when relatives or Jewish organizations discovered them, they were typically apprehensive and sometimes resistant to yet another change.

As areas were liberated from German rule, Jewish organizations rushed in to locate survivors and reunite families. In place after place, they faced the devastation wrought by the Holocaust. In Lodz, Poland, for example, the Nazis had reduced a prewar Jewish population of more than 220,000 to less than 1,000.

Following the war, Jewish parents often spent months and years searching for the children they had sent into hiding. In fortunate instances, they found their offspring with the original rescuer. Many, however, resorted to tracing services, newspaper notices, and survivor registries in the hope of finding their children.

Time and again, the search for family ended in tragedy. For parents, it was the discovery that their child had been killed or disappeared. For hidden children, it was the revelation that there were no surviving family members to reclaim them.

Custody Battles and Orphans

In hundreds of cases, rescuers refused to release hidden children to their families or Jewish organizations. Some demanded that the child be “redeemed” through financial remuneration. Others had grown attached to their charges and did not want to give them up. In the more difficult cases, courts had to decide to whom to award custody of the child. Some rescuers defied court decisions and hid the children for a second time.

The future of the thousands of orphaned Jewish children became a pressing matter. In the Netherlands, more than half of the 4,000 to 6,000 surviving Jewish children were declared “war foster children” (Oorlogspleegkinderen), and most were placed under a state committee's guardianship. The vast majority were returned to a surviving family member or a Jewish organization, but more than 300 were given to non-Jewish families.

Torn Identity

Parents, relatives, or representatives of Jewish organizations who came to reclaim the children often encountered ambivalence, antagonism, and sometimes resistance. After years of concealing their true identity, Jewishness for some hidden Jewish children had come to symbolize persecution while Christianity stood for security. Some children even repeated antisemitic phrases learned from classmates and adults. Those who had been too young to remember their parents knew only their adopted family, religion, and often nationality. Many truly loved their foster families and refused to be given into the arms of a “stranger.” In a few instances, some youngsters had to be physically taken from their foster families. For a number of hidden children, the war's end did not bring an end to the traumatic experiences.

Preserving Memory

Immediately after the war, Holocaust survivors began to document the Nazis' crimes against the Jewish people, record their experiences, and memorialize those who were killed. The efforts were often painful journeys into the recent past. By 1948, Jewish organizations in Poland, Hungary, and Germany had compiled more than 10,000 written testimonies.

Hundreds of former hidden children recounted the especially difficult pain of their survival. Many sought to recover a past that the Nazis had stolen from them—families they had never known or were only distant memories, even their own given names. Others were shocked to learn of being Jewish. By delving into the shadowy recesses of their former lives, these special survivors preserve the memory of parents who bore them, rescuers who saved them, and a time that threatened to engulf them.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Why were children especially vulnerable to Nazi persecution?

- What risks, pressures, and motivations confronted rescuers when they tried to help children?

- What challenges faced hidden children and their families after liberation?

- Do children continue to be especially vulnerable in times of upheaval?