Hodonín U Kunštátu (Hodonín bei Kunstadt) (Roma camp)

After being established in March 1940 as a penal labor camp for "anti-social elements," the camp in Hodonín u Kunštátu was reclassified as an internment camp in January 1942, and finally became a “gypsy camp” in March 1942, a de facto concentration camp for Romani that served as a transfer station on the way to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

- Pre-1939: Hodonín u Kunštátu, Jihomoravský kraj, Czechoslovakia

- 1939-1945: Bezirk Boskovice, Oberlandratsbezirk Brünn-Land, Land Mähren, Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren

- post-1993: Jihomoravský kraj, Czech Republic

Hodonín u Kunštátu (Hodonin bei Kunstadt) is a tiny village in the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands, about 23 miles (37 kilometers) north of Brno. Occasionally referred to as “Hodonín,” the village should not be mistaken for the town of Hodonín, located 34 miles (54 kilometers) southeast of Brno near today’s border between the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Witnesses and former prisoners occasionally refer to the camp as “Hodonínek” (“Little Hodonín”).

The history of the camp in Hodonín u Kunštátu follows a pattern similar to the infamous Lety u Písku camp. The two camps were created at the same time, their prisoner populations were similar, and they shared some administrative personnel and guards. Like Lety u Písku, the camp in Hodonín u Kunštátu was first established by the Protectorate Ministry of Interior to "educate" those deemed "anti-social elements" through forced labor. Similar to Lety u Písku, the history of the Hodonín u Kunštátu camp can also be divided into three phases. After being established in March 1940 as a penal labor camp for "anti-social elements," it was reclassified as an internment camp in January 1942, and finally became a “gypsy camp” in March 1942, a de facto concentration camp for Romani that served as a transfer station on the way to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In the first penal labor camp phase, the prisoner population consisted of inmates from the Brno workhouse (Zemská donucovací pracovna v Brně). With a maximum capacity of 300 inmates and average occupancy of 150, about 1,500 Czech males passed through the camp between March 1940 and March 1942. Its purpose was to provide a labor force for the construction of the Pilsen-Ostrava highway. Inmates from the notorious Lety u Písku camp were assigned to work on a different segment of the same highway project.

An official in the area from Landesbehörde Brünn issued regulations for camp operations on March 27, 1941, as Directive No. 7652-I/7, signed by Jung, the regional president. The directive specified implementation measures for a related directive issued the previous month. According to this lengthy document—issued in Czech and German—only inmates found medically fit for physical labor were to be admitted to the camp. A three-tier system was set up similar to the one in Lety u Písku. Inmates were categorized according to their sentences and conduct, with “well-behaved” class one prisoners released after three months and class three prisoners after six months or more. During this first phase, sick or injured inmates in theory could have been released temporarily until they had recovered fully. While these rules for the length of sentences were followed to some degree during the “penal camp” stage, the rules for inmate release were no longer observed as time went by, and only a handful of prisoners were released. The majority of the prisoners were Czech nationals. Czech Romani represented about 10 to 15 percent of the prisoner population and because the camp was not initially considered a “gypsy camp,” Romani men were being sent to it on the pretext that they were “anti-social elements." However, as was the case in Lety u Písku, the letter “C” (for cikán, that is, "gypsy") was put next to Romani names on prisoner lists throughout the whole history of the camp, which points to the existence of underlying racial motives from the start.

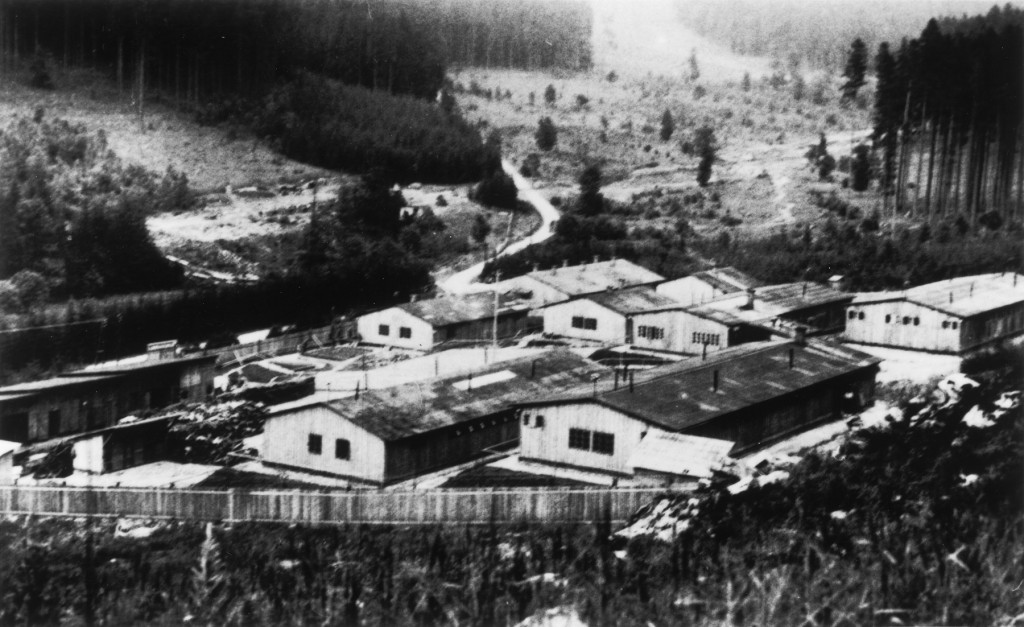

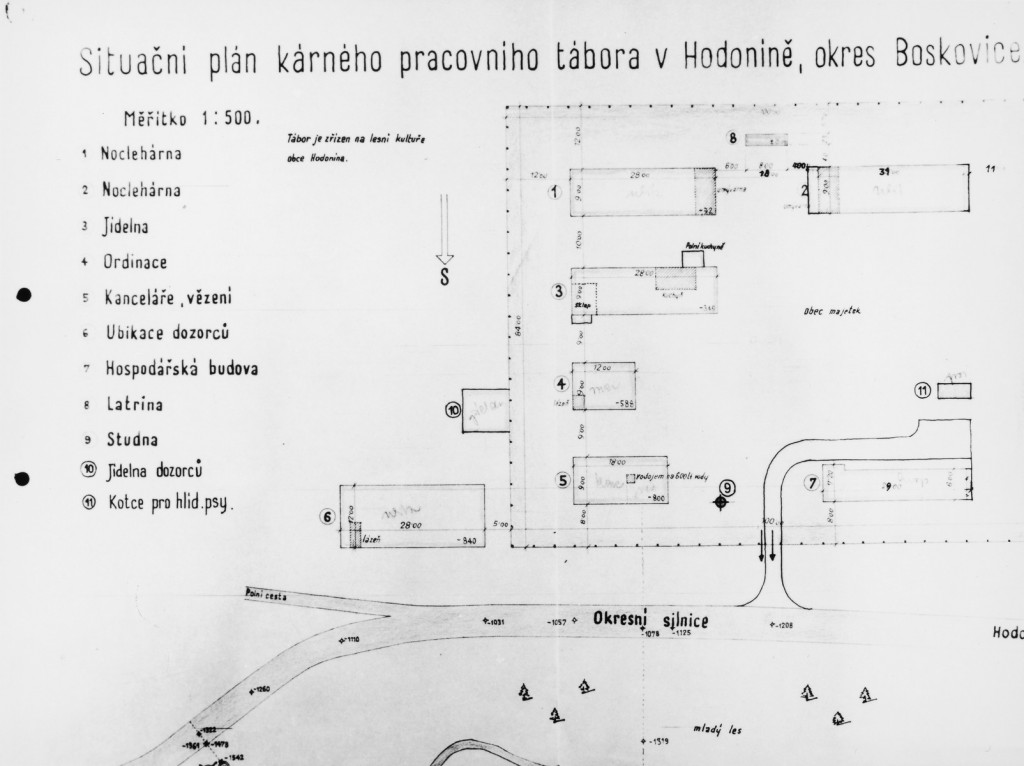

The camp was located about 600 meters from the village of Hodonín at the edge of the “Ubčina” forest in a hilly area and was difficult to access. It originally consisted out of three large barracks for prisoners, only two of which were habitable during the winter. Four additional smaller barracks were used for the kitchen, infirmary, accounting office, and administration. The camp’s water supply came from a single well. Dog kennels and latrines were also located within the area where prisoners lived, which was surrounded by a wooden fence. Outside the fenced-in area, additional barracks served the camp guards, providing living quarters, a kitchen with a mess hall, a water tank, and some smaller barracks occupied during the summer season. The camp had no sewer system and dry latrines were used instead. Electrical wires and water pipes were only laid in late 1942 or early 1943 by the inmates of the “gypsy camp." The barracks were already in poor condition at the time the camp was established, suffering from roof leaks and walls that did not provide adequate protection against the elements. Yet as long as the inmate population limit was not exceeded and the inmates were healthy, conditions remained somewhat manageable and no deaths caused by poor living conditions were reported during the “penal camp” phase of Hodonín. This stood in stark contrast to what occurred later.

On July 10, 1942, the General Commander of the Protectorate Plainclothes Police issued an order to combat "the Gypsy nuisance," which meant full implementation of the German Nazi anti-gypsy legislation in the Protectorate. Lists of about 11,500 persons considered “gypsies” were compiled, and these people were systematically concentrated in the former penal labor camps of Lety u Písku and Hodonín u Kunštátu. Both the camps were reclassified and in the summer of 1942 and most of their non-Romani inmates were either released or transferred elsewhere in early August 1942. The Romani prisoners were ordered to stay and they became the core of the new Romani-only prisoner population.

The “gypsy camp” in Hodonín u Kunštátu existed for eighteen months, from August 1942 until it was disbanded in September 1943. In September 1942, the regional governor at the Landesbehörde Brünn moved two additional large used barracks to Hodonín in order to expand its maximum occupancy to 800. These additional barracks were originally meant to house women and young girls, but they were later used as quarantine quarters instead. The maximum occupancy was quickly exceeded by more than 40 percent: the average prisoner population after September 1942 rose to around 1,200 and continued to grow, reaching 1,300. This brought many new problems, such as equipment and fuel shortages, overcrowded rooms, an inadequate water supply, poor sanitation facilities, and the outbreak of epidemics. The camp administration attempted to deal with overcrowding by setting up additional improvised prisoner housing, which for a short period of time in the summer and autumn of 1942 even included tents and caravans confiscated from incoming nomadic Romani families.

The camp was headed by the Czech high administrative official Štefan Blahynka from the Protectorate gendarmerie, who remained in this position from 1940 to 1944. He was reassigned to the Lety u Písku for a short time between January 1943 and May 1943, where he was tasked with managing the typhoid outbreak and preparing the camp for its “evacuation” to Auschwitz-Birkenau. After finishing his duties in Lety, he returned to Hodonín. Blahynka has been described as stern, strict, and cold-blooded. During his temporary reassignment to Lety, Blahynka was replaced by a first lieutenant of the Protectorate police, Jan Sokl. Bedřich Hejl, Václav Caha, Antonín Růžička (reassigned to Lety for a short time as well), and Ladislav Dočkal also performed administrative functions. The number of guards fluctuated between the minimum of 32 and maximum of 44. All of the administrative personnel and guards were Czechs, yet they were subordinated first to the Protectorate Ministry of the Interior during the “penal camp" phase and then to the German-controlled GKNP during the “gypsy camp” phase. Kapos selected from the most cruel and vicious inmates were also used in the camp.

In contrast to the early phase, the prisoner population of “gypsy camp” consisted mostly of Romani. This time whole families, including elderly people, pregnant women, children, toddlers, and newborns were crammed into barracks that were barely suitable for healthy adult males. Upon arrival, the inmates were forced to hand over all their property, including clothes and personal items. Money and valuables were confiscated. The incoming inmates were supposed to receive camp clothing, mattresses, blankets and two pairs of shoes; however, due to shortages, only several hundred of these items were actually available for the more than one thousand inmates. The severe shortage of clean adequate clothing and other items continued throughout the whole history of the camp and was in part responsible for the epidemic outbreaks that occurred in the winter of 1942 and spring of 1943.

The inmates were initially assigned work in highway construction. This included mining and crushing stones into gravel, leveling the terrain, transporting heavy construction material such as dirt, sand, and gravel, or removing trees. Women and children were assigned to this difficult work as well. Witnesses reported cases of mothers crushing stones to gravel with a hammer, while carrying their newborn children on their backs. The work was performed without proper equipment or protective gear, and food rations remained insufficient due to shortages and theft by the guards and despite regulations stipulating that prisoners performing heavy labor be given increased rations. The office of the GKNP justified this by claiming that because gypsies were reluctant to work and would only perform their tasks through coercive measures, they did not deserve rations appropriate for heavy labor.

The health of many of the inmates was already greatly compromised even without the outbreaks of illness and severe conditions of the camp. As an ophthalmologist from Brno discovered, 1 out of 10 of the prisoners was infected with Chlamydia trachomatis, a common cause of infectious blindness. There were two dozen cases of untreated measles among children at the camp, two dozen cases of untreated syphilis, fourteen cases of open tuberculosis, and other severe problems. In May 1943, only 5 to 10 percent of the inmates could have been considered healthy. The typhoid outbreak and tuberculosis claimed lives of two hundred inmates. The camp administration provided only minimal care in order to prevent outbreaks from spreading outside the camp and to ready prisoners for transports on which only those without visible infectious diseases could be sent. A Czech physician, MUDr. Josef Habanec, provided medical care. After the typhoid outbreak, an additional Jewish doctor, MUDr. Alfréd Mílek, was transferred to the camp in line with Nazi doctrine, according to which Jewish doctors could provide treatment only for “inferior races." After Mílek’s transport to Auschwitz-Birkenau, another Jewish doctor, MUDr. Miroslav Bohin, was assigned to Hodonín.

The prisoner lists of the gypsy camp in Hodonín u Kunštátu contained 1,355 names. Of these, 267 were released, 67 managed to escape, and 207 died directly in the camp, mainly due to infectious diseases. One hundred and eighteen bodies were buried at the Roman Catholic cemetery in Černovice, 71 more were thrown into a mass grave dug in the nearby the Koryta Forest. A total of 863 prisoners was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in September 1943, where most of them were killed shortly after arrival. The two largest transports of Hodonín inmates to Auschwitz-Birkenau took place on December 7, 1942 (78 prisoners) and August 21, 1943 (766 prisoners) after being postponed several times due to quarantine precautions.

The barracks in Hodonín remained in use even after the transport and murder of most of the “gypsy camp” prisoners. The now empty barracks were used as a training facility by the Wehrmacht for a short time in the winter of 1944 and summer of 1945. In May and June 1945 the barracks were used to house Romanian military units and in the summer of 1945, as a Red Army military hospital. During the expulsions of ethnic Germans from the Sudetenland in 1946, the barracks were used to intern those who were not physically capable of leaving the area due to their advanced age or to health concerns. About 80 of them died in the camp. In 1949, a forced labor camp was established by the communist regime in the same barracks, which existed there until 1950. As of 1952 the facility was used as a training and recreational camp for the communist prison service. It served as a summer holiday "pioneers camp" for the communist youth and was converted into a commercial vacation spot after 1989. Only in 2009 was the area, dubbed by the locals as “Žalov," bought by the Czech Ministry of Education in order to reconstruct it and transform it into a Holocaust memorial. At least two barracks, one prisoner barracks and one barracks for housing the guards had survived in almost their original state. Reconstruction and preservation works are currently being performed to transform the site into a museum and memorial for the Porajmos (the Roma Holocaust).

Sources

Archival evidence is located in multiple institutions. Documents of the central administration, the GKNP office, are held by the Czech National Archive in the GVNP collection. The Moravian State Archive in Brno holds additional documents on the establishment of the camp and some of its administrative affairs in collection B 251 – Říšský protektor v Čechách a na Moravě, služebna pro zemi Moravu, Brno, or in the Museum of Romany Culture in Brno. This entry draws extensively on Ctibor Nečas’s The Holocaust of the Czech Roma, which provides the most detailed and balanced account of the camp’s history. The same author has also published a condensed version in English. For a collection of witness testimonies by former prisoners as well as by the citizens of Hodonín, see the memorial volume Ma Bisteren – We Will Not Forget, compiled by Nečas during his research.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

Ružena Bubeníčková, Ludmila Kubátová, and Irena Malá, Tábory utrpení a smrti (Prague: Svoboda, 1969), p. 212.

-

Footnote reference2.

Domácí a denní řád trestního pracovního tábora Hodonín u Kunštátu. Říšský protektor v Čechách a na Moravě, služebna pro zemi Moravu, Brno. Moravian State Archive in Brno, box 40, Invent. číslo 483

-

Footnote reference3.

Ctibor Nečas, Ma Bisteren – Nezapomeneme: Historie cikánského tábora v Hodoníně u Kunštátu (1942-1943) (Prague: Muzum romské kultury, 1997), p. 6.

-

Footnote reference4.

Ctibor Nečas, Holocaust českých Romů (Prague: Prostor, 1999), p. 71. They had been dismantled at another site and rebuilt at the camp, a common practice due to shortages of construction materials.

-

Footnote reference5.

Ctibor Nečas, Holocaust českých Romů (Prague: Prostor, 1999), p. 77.

-

Footnote reference6.

Interview with citizen B.M. from the village of Hodonín, as quoted in Nečas, Ma Bisteren, p. 34.

-

Footnote reference7.

Ctibor Nečas, Holocaust českých Romů (Prague: Prostor, 1999), pp. 101-102.

-

Footnote reference8.

Ctibor Nečas, Holocaust českých Romů (Prague: Prostor, 1999), p. 77.

-

Footnote reference9.

Ctibor Nečas, Holocaust českých Romů (Prague: Prostor, 1999), p. 83.

-

Footnote reference10.

Ctibor Nečas, Ma Bisteren – Nezapomeneme: Historie cikánského tábora v Hodoníně u Kunštátu (1942-1943) (Prague: Muzum romské kultury, 1997), pp. 14-19.

-

Footnote reference11.

http://zapomnicky.pamatnik-terezin.cz/index.php/olbramovice?id=282#sdfootnote6sym převzato (accessed 14 August 2018).

-

Footnote reference12.

Ctibor Nečas, “Bohemia and Moravia - Two Internment Camps for Gypsies in the Czech Lands,” in In the Shadow of the Swastika, vol. 2, ed. Donald Kenrick (Hertfordshire: University of Hertfordshire Press, 1999), pp. 149-170.

-

Footnote reference13.

Ctibor Nečas, Ma Bisteren – Nezapomeneme: Historie cikánského tábora v Hodoníně u Kunštátu (1942-1943) (Prague: Muzum romské kultury, 1997), p. 6.

Critical Thinking Questions

To what degree was the local population aware of this camp, its purpose, and the conditions within? How would you begin to research this question?

Where were camps located?

What choices do countries have to prevent, mediate, or end the mistreatment of imprisoned civilians in other nations?

Investigate the persecution that Roma still face in parts of Europe today.