Making a Leader

“How many look up to him [Hitler] with touching faith as their helper, their savior, their deliverer from unbearable distress.”

—Louis Solmitz, Hamburg schoolteacher, 1932

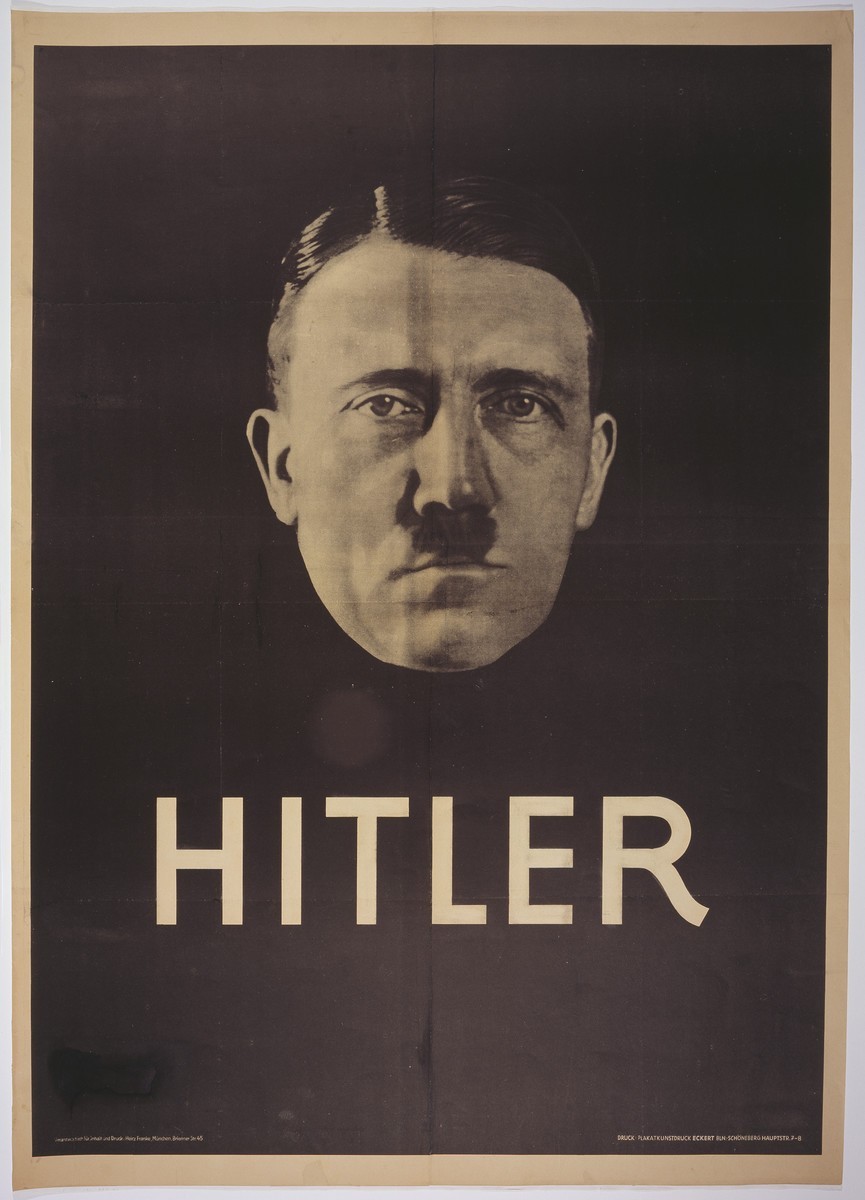

Intense public desire for charismatic leaders offers fertile ground for the use of propaganda. Through a carefully orchestrated public image of Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler, during the politically unstable Weimar period the Nazis exploited this yearning in order to consolidate power and foster national unity.

Nazi propaganda facilitated the rapid rise of the Nazi Party to a position of political prominence and, ultimately, the control of a nation by the Nazi leadership. In particular, election campaign materials from the 1920s and early 1930s, as well as compelling visual materials and vigilantly controlled public appearances, coalesced to create a “cult of the Führer” around Adolf Hitler. His fame only grew via speeches he delivered at mass rallies, parades, and on the radio. In this public persona, Nazi propagandists cast Hitler as a soldier at the ready, as a father figure, and ultimately as a messianic leader brought to redeem Germany.

Modern techniques of propaganda—including strong images and simple messages—helped propel the Austrian-born Hitler from a little known extremist to a leading candidate in the 1932 German presidential elections. World War I propaganda significantly influenced the young Hitler, who served as a soldier on the front from 1914 to 1918. Like many others, Hitler firmly believed that Germany lost the war not because of defeat on the battlefield, but as a result of enemy propaganda. He surmised that the victors of World War I (Britain, France, the United States, and Italy) had pounded home clear, simple messages that encouraged their own forces while sapping the German will to fight. Hitler understood the power of symbols, oratory, and image, and formulated party slogans to reach the masses that were simple, concrete, and emotionally appealing.

From 1933 to 1945, public adulation for Adolf Hitler was an ever present feature in the public square of German life. Nazi propagandists portrayed their leader (Führer) as the living embodiment of the German nation, radiating strength and a single-minded devotion to Germany. Public notices reinforced the theme of Hitler as savior of a German nation beaten down by the terms of the post-World War I Treaty of Versailles. The cult of Adolf Hitler was a deliberately cultivated mass phenomenon. Both Nazi propagandists and artists produced paintings, posters, and busts of the Führer, which were then reproduced in large quantities for public venues as well as private homes. The Nazi Party publishing house printed millions of copies of Hitler's political autobiography, Mein Kampf (My Struggle) in special editions, including editions for newlyweds and translations into Braille for blind persons.

Nazi propaganda idolized Hitler as a gifted statesman who brought stability, created jobs, and restored German greatness. Under the Nazi regime, Germans were expected to pay public allegiance to the “Führer” in quasi-religious forms, such as giving the Nazi salute and greeting others on the street with “Heil Hitler!,” the so-called “German Greeting.” Faith in Hitler strengthened the bonds of national unity, while non-compliance signaled dissension in a society where open criticism of the regime, and its leaders, were grounds for imprisonment.