Varian Fry

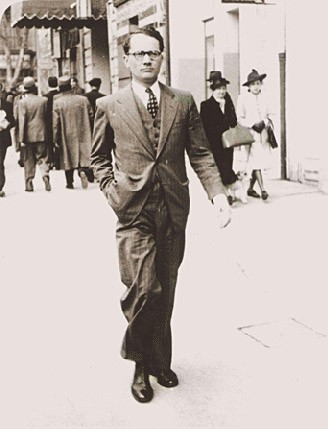

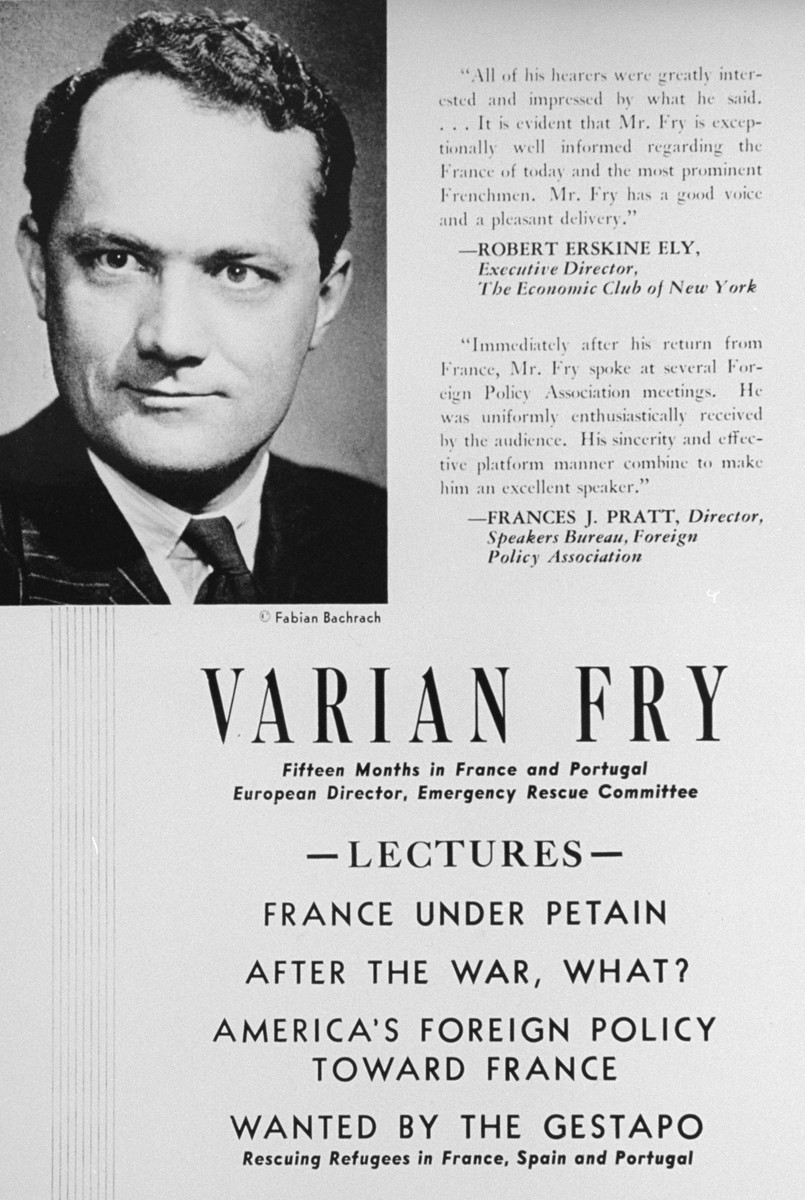

Varian Fry (1907–1967) was an American journalist who helped refugees escape from France in 1940–1941. In August 1940, he was sent to the French city of Marseille by the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC), a private American aid organization. Fry’s task was to help artists, writers, and anti-Nazi refugees escape from France, which surrendered to Nazi Germany on June 22, 1940.

Key Facts

-

1

After France surrendered to Nazi Germany in June 1940, a group of notable Americans established the Emergency Rescue Committee. Their mission was to rescue prominent artists and intellectuals trapped in France.

-

2

Fry and his staff used legal and illegal means to help some 2,000 people escape France.

-

3

Varian Fry was the first American to be recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem.

The responses of non-Jewish individuals to the Holocaust varied and depended on many factors. Most individuals were reluctant to help Jews because of fear, self-interest, greed, antisemitism, and political or ideological beliefs. Others chose to help because of religious or moral conviction, or based on the strength of personal relationships. This article is about Varian Fry, an American who helped refugees escape from southern France.

Varian Fry (1907–1967) was an American journalist who helped anti-Nazi refugees, including both Jews and non-Jews, escape from France during World War II.

Varian Fry: Background and Motivations

Varian Fry was born in New York City on October 15, 1907. He grew up in Ridgewood, New Jersey. Fry graduated from Harvard University in 1931 with a degree in classics. After graduation, he moved to New York City and married Eileen Hughes. Hughes was an editor at the Atlantic Monthly. In New York, Fry worked as a journalist and editor for various magazines. He became increasingly interested in foreign affairs. In 1935, Fry traveled to Berlin, the capital of Nazi Germany, to report on what he saw there.

During his visit to Berlin, Fry witnessed an anti-Jewish riot on July 15, 1935. He was horrified by what he observed. His account of the violence appeared in The New York Times:

I saw one [Jewish] man brutally kicked and spat upon as he lay on the sidewalk, a woman bleeding, a man whose head was covered with blood, hysterical women crying… Nowhere did the police seem to make any effort whatever to save the victims from this brutality.

—Varian Fry, quoted in The New York Times

This experience shaped Fry’s view of the Nazis. According to his own account, it later inspired him to go to France to help refugees.

In the late 1930s, Fry wrote several books on international affairs for the Foreign Policy Association. Through his writing and activism, he met many New York intellectuals who had strong ties to Europe and who shared his interest in politics, the arts, and literature. These relationships ultimately made him more invested in the fate of European writers, politicians, and artists targeted by the Nazi regime.

Responding to the Fall of France, 1940

Fry became involved in helping refugees in 1940, after Germany invaded and occupied France. That summer, the situation in France created a unique opportunity for American rescue efforts, for three reasons:

- France was divided into two main zones, one unoccupied;

- France had been a safe haven for many prominent anti-Nazi refugees; and

- the United States maintained diplomatic relations with France.

Furthermore, tens of thousands of people were desperate to escape Nazi persecution. It was in response to these circumstances that Fry traveled to France.

Germany’s Rapid Defeat of France and Its Consequences

In May–June 1940, Nazi Germany invaded and quickly defeated France. The French government signed an armistice with the Germans on June 22. Shortly afterwards, new leaders who collaborated with the Nazis took over the French government. This new government was known as the Vichy regime or Vichy France.

The Vichy regime was officially independent, but a large portion of its territory was under German occupation. As part of the terms of the French surrender, the German military occupied the northern and western parts of the country. This area was known as the occupied zone (zone occupée). It included the city of Paris. In this zone, the Vichy regime had to cooperate fully with German occupation authorities. The southern unoccupied zone was called the free zone (zone libre). From summer 1940 to November 1942, this area was not directly controlled by German occupation forces. In theory, measures of the Vichy government applied to both the occupied and unoccupied parts of France. However, the new government could only govern autonomously in the free zone.

The Refugee Crisis in Southern France, 1940

The German invasion of western Europe created a refugee crisis. Millions of people fled to southern France to escape the advancing German forces. Many had real reason to fear falling into Nazi hands. Among those fleeing south were tens of thousands of refugees who had come to France to escape Nazi oppression in Germany and other Nazi-controlled areas. These refugees included thousands of Jewish people, as well as artists and intellectuals who had openly criticized the Nazis.

The "Surrender on Demand" Clause

For many refugees, however, southern France was not safe. The Vichy regime imprisoned thousands of non-French refugees in internment camps as “enemy aliens.” It passed anti-Jewish laws and collaborated with the Germans. The French-German armistice included a “surrender on demand” clause. This clause, located in Article 19 of the document, stated, “The French Government is obliged to surrender upon demand all Germans named by the German Government in France.” This meant that many German refugees who had fled to France were in danger of being turned over to the Nazis if caught by French police.

Fry and many of his friends found this “surrender on demand” clause particularly offensive.

Establishing the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC), 1940

In the United States, many people, including Fry, wanted to help the refugees who were now seemingly trapped in France. Fry had befriended Paul Hagen (born Karl Frank). Hagen was a German political opponent of the Nazis who founded the organization “American Friends of German Freedom.” In May and June, as it looked like Germany would defeat France, Fry and Hagen began to discuss raising money and organizing a relief effort.

“American Friends of German Freedom” decided to host a fundraising luncheon featuring prominent Americans. To attract attendees, the event officially honored Raymond Graham Swing, a famous radio personality. On June 25, 1940, more than 200 notable Americans gathered at the Hotel Commodore in New York for the event. This was just three days after France and Germany signed the armistice.

Many people spoke at the luncheon about the plight of refugees in France. Attendees donated $3,500 to the cause. The assembled group also decided that a new relief agency would be necessary to focus on the problem. They created the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC).

Goals of the ERC

The goal of the ERC was to rescue intellectuals in France who faced danger from the Nazis due to the “surrender on demand” clause. The ERC vowed to aid anti-Nazi writers and artists (both Jews and non-Jews), who were likely to be targeted by Nazi German authorities. Some of these people were French citizens. Others were refugees who had fled Nazi Germany, Austria, and elsewhere.

The ERC’s board included Dr. Frank Kingdon (the ERC’s chairman and the president of the University of Newark); journalist Dorothy Thompson; radio personality Elmer Davis; and Dr. Alvin Johnson (the president of the New School, a newly-founded college in New York City that employed refugee professors).

Arranging Emergency Visitor Visas

The ERC in New York created a long list of people they believed were in danger in southern France. To help these refugees, the ERC needed a way to get them to the United States. But this was difficult. The United States had no refugee or asylum policy at the time. People wishing to immigrate through established channels had to apply for the limited number of quota visas available each year.

However, in 1938, after the German annexation of Austria, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had created “The President’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees.” This was a group of prominent Jewish and non-Jewish men who advised the president. The group also connected private aid organizations with the federal government.

In response to the President’s Advisory Committee’s advice, the Roosevelt administration created an emergency visitor visa program. Emergency visitor visas were long-term, non-immigrant visas.

The ERC planned to help some refugees come to the United States using emergency visitor visas. Other refugees waited for quota immigrant visas. The ERC planned to help them with that paperwork and the additional documents they would need to immigrate to the United States.

Sending Varian Fry to Marseille, France

The ERC decided they needed a representative in southern France to locate and aid the refugees they had identified. Fry volunteered. Fry later wrote that he was motivated to go to France because of what he had seen in Germany in 1935. He also deeply admired many of the approximately 200 politicians, artists, and intellectuals on the ERC’s lists. The ERC originally estimated that Fry would only need a month in France to complete the work.

In early August 1940, Fry arrived in Marseille, a large French port city on the Mediterranean in the unoccupied free zone. At the time, Marseille was an especially popular destination for refugees. It was not far from the French-Spanish border. A number of American aid organizations had offices in the city. By this time, one of the only remaining exit routes out of occupied Europe was through Spain and Portugal. Neither country was occupied by Nazi Germany or fighting in World War II. Marseille also still had an American consulate, which was essential for people trying to get visas to enter the United States.

Thus, Marseille was the ideal place for Fry to set up his aid operation.

Varian Fry and the ERC’s Rescue Efforts in France, 1940–1941

Almost immediately after he arrived in Marseille in August 1940, Fry began meeting with refugees and helping them devise means of escape. He initially operated out of his hotel room at the Hotel Splendide. Fry quickly realized that his work would take longer than a month. The ERC approved his request to stay in France. In late August, Fry formally established an office known as the Centre Américain de Secours (American Rescue Center). The organization’s offices were originally on Rue Grignan and later relocated to a space on the Boulevard Garibaldi, both in the central part of the city.

Fry’s Staff and Colleagues

Fry did not work alone. In Marseille, he gathered a dedicated staff that included both Jewish and non-Jewish refugees. Among the Jewish refugees on the staff were:

- the Viennese artist and cartoonist Willi Freier (born Wilhelm Spira, also known as Bill Spira), who helped forge passports and passport stamps;

- Justus Rosenberg, a teenager from Danzig, who later became a professor at Bard College in New York; and

- Albert O. Hirschman (born Otto Hirschmann), a refugee from Berlin who later became a well-known economist.

The staff also included American expatriates: artist Miriam Davenport, who helped select refugees; heiress Mary Jayne Gold, who helped fund the work; Leon “Dick” Ball, who escorted refugees to the border; and Charlie Fawcett, who acted as the office’s reception clerk and security guard.

There were multiple refugee aid organizations operating in Marseille. Fry and his staff worked with like-minded Americans to help the refugees. Fry quickly befriended American socialist Frank Bohn, who worked for the American Federation of Labor. Bohn was in Marseille to help European labor leaders escape the Nazis. Bohn connected Fry with the people he needed to know in Marseille. Fry also met American vice consul Harry Bingham Jr., who was very sympathetic to the plight of refugees. By the time Fry arrived in France, Bingham was already hiding German novelist Lion Feuchtwanger in his home. Bingham helped Fry whenever he could.

Fry’s Activities in Marseille

Some refugees already had valid US immigration visas. Thus, they did not need help from the ERC to obtain an emergency visitor visa. They just needed help escaping France. In such cases, Fry’s office would provide the refugees with money or other resources until they could safely leave France. Fry also helped some refugees get released from French internment camps.

When necessary, Fry was also willing to resort to illegal methods to help refugees escape France. For example, some refugees lacked a French exit visa. In these cases, Fry and his colleagues connected them with guides, who would help them leave France illegally by walking over the Pyrenees mountains from France into Spain. In certain cases, Fry even helped refugees acquire forged passports or had Willi Freier forge stamps into their existing passports.

The Villa Air-Bel

By the fall of 1940, the ERC staff had located and rented an abandoned villa about a half hour outside of Marseille. The Villa Air-Bel provided a home for Fry, some of the ERC staff, and some of the refugees who needed a safe place to live. One refugee nicknamed it the “Château Esper-Visa” (Château Hope for a Visa).

Fry’s Clash with the US State Department

French authorities quickly learned about Fry’s activities. Some refugees shared the story of their escape with American newspapers. This made it clear to both American and French officials that the ERC was helping refugees cross the border illegally.

At the time, the United States was officially neutral in World War II and still maintained a diplomatic relationship with the Vichy French regime. In September 1940, Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long instructed American diplomats to tell both Bohn and Fry that the United States could not support their illegal activities in France.

Following this warning, Bohn returned to the United States. Fry, however, continued his work in France for nearly a year. The State Department warned him multiple times to obey Vichy French laws, but the Centre Américain de Secours continued to operate both legally and illegally.

Whom did Varian Fry Help?

We couldn’t help everybody in France who needed help….And we had no way of knowing who was really in danger and who wasn’t. We had to guess, and the only safe way to guess was to give each refugee the full benefit of the doubt. Otherwise we might refuse to help someone who was really in danger and learn later that he had been dragged away to Dachau or Buchenwald because we had turned him down.

—Varian Fry, in his memoir Surrender on Demand

Fry and the ERC helped about 2,000 people escape from southern France. Among them were a number of famous artists, intellectuals, and their families. They included:

- Jewish artist Marc Chagall;

- French surrealist author André Breton;

- French artist André Masson;

- German artist Max Ernst;

- Jewish sculptor Jacques Lipchitz;

- Polish Jewish harpsichordist Wanda Landowska;

- German philosopher Heinrich Blücher and his wife Hannah Arendt, who was Jewish and later became a prominent political theorist;

- German author and Nazi critic Heinrich Mann;

- German Jewish poet Walter Mehring;

- German Jewish writer Lion Feuchtwanger; and

- Austrian Jewish author Franz Werfel.

In addition to prominent refugees, Fry also helped other people who simply needed assistance. Among them was Margit Meissner.

Fry’s Expulsion from France, 1941

Fry was under constant surveillance by French authorities. He was questioned and detained multiple times. On August 29, 1941, French police arrested him. After a night in police custody, he was given two hours to pack his belongings before being escorted to the Spanish border. Ironically, he had to wait at the border for about a week because he did not have valid exit or transit visas to leave France. From there, he traveled to Lisbon, Portugal, which had become the main port of exit for refugees going to the United States. Fry briefly continued his work for the ERC from Lisbon before returning to the United States in early November 1941.

Daniel Bénédite, a French non-Jew who had been Fry’s deputy, continued to run the Centre Américain de Secours’s offices in Marseille until it was raided by French police in June 1942.

A little over a month after Fry returned home, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States was drawn into World War II.

Fry’s Work During the Remaining Years of World War II

Soon after his return to the United States, the Emergency Rescue Committee severed ties with Fry due to his outspoken criticism of the State Department. In 1942, the ERC merged with another organization. This organization became known as the International Rescue and Relief Committee (today, the International Rescue Committee).

Fry began a new job as the assistant editor of The Nation magazine. He also began writing a book about his experiences in France. In December 1942, after information about the mass murder of Jews reached the United States, Fry wrote an article for The New Republic magazine titled “The Massacre of the Jews.” He exhorted readers that all the evidence adds up to “the most appalling picture of mass murder in all human history.”

Fry continued to criticize the State Department publicly. He offered to join the Office of Strategic Services (OSS; the precursor to contemporary US foreign intelligence agencies). As part of his offer, he proposed to gather intelligence, return to France as part of the American military, and serve as a representative of the War Refugee Board, created in 1944 by President Roosevelt to rescue Jews and other persecuted minorities. The government and military rejected all of his offers.

Varian Fry’s Memoirs and Life after the War

In 1945, Fry published Surrender on Demand, his memoir about his relief work in France. Fry and his wife, Eileen, separated in 1942; she passed away in 1948. Fry then married Annette Riley, with whom he had three children.

Fry began to write freelance for businesses. He also started teaching high school and college.

In 1963, the International Rescue Committee honored Fry for his “contributions to the cause of freedom.” He was able to reunite with some of the artists he had assisted. He asked them to contribute work to a fundraising lithograph series. Some participated; others declined.

Varian Fry died in 1967 at age 59. He had been revising his 1945 memoir Surrender on Demand for a student audience. This memoir, now titled Assignment: Rescue, was published in 1968.

Postwar Recognitions and Honors

Shortly before his death, the French government awarded Fry the Croix de chevalier de la Légion d'honneur, one of France’s highest decorations of merit. It was the only official government recognition he received in his lifetime.

In 1991, the United States Holocaust Memorial Council posthumously awarded Fry the Eisenhower Liberation Medal. Three years later, Fry became the first American to be recognized by Yad Vashem (Israel’s official memorial to Holocaust victims) as Righteous Among the Nations.

In 2000, the square in front of the US consulate in Marseille was renamed Place Varian Fry.

Fry has been the subject of numerous non-fiction and fiction books and movies.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

"Editor Describes Rioting in Berlin; Varian Fry of The Living Age Tells of Seeing Women and Men Beaten and Kicked,” New York Times (New York, NY), July 27, 1935.

-

Footnote reference2.

Varian Fry. Surrender on Demand (Scranton, PA: Random House, 1946), 31.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have affected Fry’s decision to attempt to rescue Jews in Europe?

How can individuals contribute to or assist in the rescue of endangered citizens of other nations?