Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus

In the late 1930s, hundreds of thousands of Jews in Nazi Germany applied to immigrate to the United States. Some American individuals and organizations tried to assist them. One Jewish American couple, Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus, brought 50 Jewish children from Vienna to the United States. The Brith Sholom organization in Philadelphia supported their efforts. It was one of the largest individual attempts to aid Jewish refugees before the outbreak of World War II.

Key Facts

-

1

Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus worked within strict US immigration laws to bring 50 Jewish children from Nazi Vienna to the United States in June 1939. The children’s families had been actively trying to escape Nazi-controlled territory.

-

2

In the United States, the children first lived at a large home in Pennsylvania. They then moved in with foster families or relatives.

-

3

While many of the children lost family members in the Holocaust, they all eventually reunited with at least one parent.

Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus were a Jewish American couple living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the spring of 1939, they grew concerned about the plight of Jewish children under the Nazi regime. With assistance from friends and colleagues, the Krauses helped 50 Jewish children leave the city of Vienna (at the time part of Nazi Germany) and come to the United States. To aid these children, the Krauses worked within existing US immigration laws.

The Krauses were one example of people trying to help Jews escape Nazi persecution before World War II. A number of Jewish and non-Jewish aid organizations in the United States assisted Jews with immigration in various ways. However, Congress did not change the immigration laws to increase the number of people who could enter the country.

An Individual Initiative: Deciding to Help Jewish Children

The Krauses became involved with helping Jewish children in January 1939 when Gilbert was approached by Louis Levine. Levine was the president of the Independent Order Brith Sholom, a Jewish fraternal organization based in Philadelphia. Gilbert was a lawyer and a member of the organization.

Levine and Kraus were alarmed by news coming out of Europe. The previous year had been tumultuous. Nazi Germany’s foreign policy and territorial expansion pushed Europe to the brink of war. That same year, the Nazi regime escalated its persecution of Jews. The Nazis used laws and state sponsored violence and terror to force Jews to emigrate. Hundreds of thousands of Jews wanted to escape Nazi persecution.

Levine and Kraus discussed traveling to Europe to assist the immigration of Jewish children to the United States. Levine offered to care for the children at a large house near the summer camp owned by Brith Sholom in Collegeville, Pennsylvania. He also promised that Brith Sholom and its members would financially support their efforts. Kraus contacted Congressman Leon Sacks, a Democrat from Pennsylvania and a longtime friend. Sacks was willing to assist with the plan.

Planning the Operation: Navigating Immigration Hurdles

To enter the United States, the refugee children would need immigration visas. These were granted by the Department of State. Congressman Sacks used his Washington connections to arrange a meeting with State Department officials. On February 3, 1939, Levine, Kraus, and Sacks met with Assistant Secretary of State George Messersmith in Washington, DC. Messersmith had served as consul general at the American consulate in Berlin, Germany, in the early 1930s. There, he had witnessed the early Nazi persecution of German Jews.

The three men presented Messersmith with their plan. They hoped to obtain the State Department’s support for Kraus to travel to Europe. There, Kraus would interview Jewish families who were in the process of immigrating to the United States. These families were willing to send their children to Pennsylvania to be cared for by Brith Sholom. Kraus would provide affidavits signed by his wealthy friends promising that the children would not become “public charges” in the United States.

At the time, at least 240,000 people born in Germany were on the State Department’s waiting lists for US immigration visas. This was well over the yearly quota of 27,370 visas allocated by Congress to immigrants (including children) born in Germany or Austria.

Messersmith pointed out that so-called “dead” visas might be available for Brith Sholom’s use. These “dead” visas were visas reserved for potential immigrants who, at the last minute, were unable to leave Germany. At the end of the quota year, on June 30, 1939, unused visas would expire. Although Messersmith made it clear that the State Department could not sponsor the effort, he agreed that the plan was feasible. He said that American diplomats in Germany would help however they could.

In Philadelphia, Eleanor Kraus gathered affidavits for the children. Each affidavit needed lots of paperwork, including bank statements, insurance policies, and tax forms. She gathered 54 affidavits from Brith Sholom members and the Krauses’ own personal network. The plan was to assist 50 children, but she gathered four extra affidavits in case the State Department rejected any as insufficient.

Resistance to the Krauses’ Plan in the United States

Some American Jewish organizations learned about the Brith Sholom plan and opposed the idea. For example, the German-Jewish Children’s Aid organization had been created in 1934 to assist Jewish children escaping Nazi Germany. By 1939, it had helped approximately 400 German Jewish children to immigrate to the United States. Despite this, German-Jewish Children’s Aid constantly struggled to raise money for its efforts. In late February 1939, the organization’s chairman wrote to the State Department. They were concerned that Brith Sholom might have made special arrangements with the State Department to obtain visas. German-Jewish Children’s Aid, by contrast, struggled to get visas for the children it was trying to help. Its supporters were also receiving fundraising requests from Brith Sholom. The State Department reassured German-Jewish Children’s Aid that Brith Sholom would be operating within the existing immigration system.

Parallel Efforts: The Wagner-Rogers Bill is Proposed in Congress

Around the same time the Krauses began their efforts in 1939, Senator Robert Wagner (D) and Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers (R) introduced identical pieces of legislation into their houses of Congress.

Commonly referred to as the Wagner-Rogers Bill, the legislation proposed that the United States admit 20,000 German refugee children over the next two years outside of the regular immigration system. The proposal, meant to emulate the ongoing British Kindertransports, was unpopular among Americans. Sixty-seven percent of Americans polled in January 1939 did not support the entrance of even 10,000 German refugee children.

Although the Krauses’ plan and the Wagner-Rogers Bill both tried to help refugee children, these efforts were not connected. The Wagner-Rogers Bill was still being debated in Congress as the Krauses carried out their efforts. In July 1939, opposition to the proposal forced Wagner and Rogers to remove the bill from consideration. Congress never voted on it.

The Krauses’ Mission: Putting the Plan into Action

In the spring of 1939, the Krauses traveled to Nazi Germany to locate and choose 50 Jewish children. Each child would use one of the Krauses’ affidavits to obtain one of the State Department’s “dead” visas. They would then leave their parents to immigrate to the United States and escape Nazi persecution.

Traveling to Nazi Germany

On April 7, 1939, Gilbert Kraus set off for Nazi Germany with Dr. Robert Schless, a friend of the Krauses. Schless, who spoke German, planned to assist Kraus in interviewing and selecting the children. As a doctor, Schless could also provide medical attention to the children on the trip to the United States. Eleanor Kraus initially remained in Philadelphia.

Kraus and Schless departed on the RMS Queen Mary, a large passenger ship that sailed between New York and Southampton, England. From there, they traveled by ferry and train to Berlin, arriving on April 14, 1939. In Berlin, they met Raymond Geist, who worked as the United States consul general. Since the United States no longer had an ambassador in Germany, Geist also served as the senior American diplomat there. Geist advised the two men to go to Vienna, where many Jewish families were waiting for the opportunity to immigrate to the United States. These families had applied for immigration a year earlier, after the German annexation of Austria. Their names were high on the waiting list for visas.

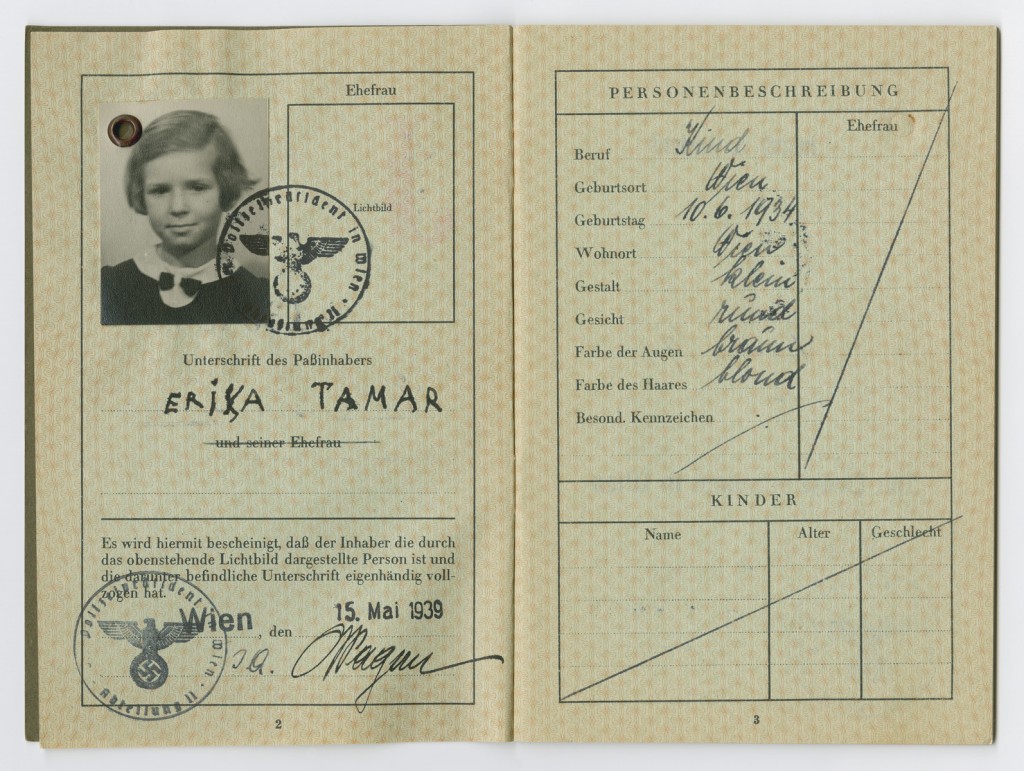

Kraus and Schless traveled by overnight train to Vienna. They immediately met with State Department staff at the US consulate and representatives of the Vienna Jewish community. The Jewish community offered space in the building for Kraus and Schless to meet and interview Jewish families. Hedy Neufeld, an Austrian medical student whose father was Jewish, assisted the two Americans. On April 17, 1939, Gilbert Kraus telephoned his wife and asked her to join him. Eleanor Kraus left the couple’s children in the care of family friends and arrived in Vienna on April 28.

Interviewing and Choosing the Children

The Krauses, Dr. Schless, and Hedy Neufeld interviewed numerous families. They decided to consider only children between the ages of four and fourteen who were, as Eleanor later wrote, “healthiest in mind and body.” By early May, the Krauses had chosen 50 children. They provided the United States consulate in Vienna with the children’s names and with the affidavits of support Eleanor had gathered in Philadelphia. Many of the children’s fathers had been arrested and imprisoned in concentration camps. The father of two of the children had died only a few weeks earlier.

The American diplomats in Vienna did not know about the plan to use “dead” visas. They also questioned whether the affidavits were sufficient guarantees of support. The Krauses took a quick trip to Berlin and met with Geist again. He reassured them that their affidavits were excellent and contacted the Vienna consulate in support of the Krauses’ plan. He also made arrangements for the children to receive medical exams in Berlin on May 22, 1939. This was the last step to receiving their visas. Geist promised that if visas became available, they would be granted to the children.

Leaving Vienna with the Children

On May 10, the Krauses asked the families of the chosen children to meet at the Jewish community building. The parents signed documents granting Gilbert Kraus temporary guardianship of their children. Over the next ten days, the Krauses and the families gathered all the remaining necessary paperwork to prepare the children for the voyage.

Before leaving Vienna, one boy, Heinrich Steinberger, fell ill and could not travel. The Krauses chose another child, Alfred Berg, whose younger sister was already on their list. According to archival records, Heinrich and his mother were murdered in the Sobibor killing center in June 1942.

On May 20, 1939, the families met at the train station. There, the children separated from their parents and boarded an overnight train to Berlin.

At the United States Consulate in Berlin

The next morning, at the US consulate in Berlin, Gilbert learned that 50 “dead” visa numbers were available for their use. Eleanor estimated that the embassy assigned about 15 additional clerks to assist the group. They interviewed the children and helped them sign their documents. The children were finally approved for immigration to the United States.

Traveling to the United States

On May 23, 1939, the Krauses, Dr. Schless, and the 50 children sailed to the United States on the S.S. President Harding. The Krauses paid stewards and stewardesses to assist with caring for the children during the voyage. Although some children suffered seasickness, most attended English classes and played games.

The children were photographed waving at the Statue of Liberty as the ship arrived in New York on June 3, 1939. News of their arrival appeared in the newspapers near stories about the St. Louis, a German ship carrying Jewish refugees. The Cuban government had just refused to let the refugees on the St. Louis land in Havana.

Dr. Schless soon returned to Europe. There, he married Hedy Neufeld and brought her to the United States as his wife.

Arrival in Collegeville, Pennsylvania

Within hours of arriving in New York, the children traveled by bus to a large house in Collegeville, Pennsylvania. The Brith Sholom organization owned the home, which was next to their summer camp for children. The Krauses returned to Philadelphia, although Gilbert visited Collegeville frequently.

Brith Sholom hired nurses, cooks, and others to care for the children. In Collegeville, the children took classes in civics and US history and improved their English.

Some American Jewish organizations continued to question the efforts of Brith Shalom and the Krauses. These organizations were concerned that Brith Sholom was not properly caring for the children. They also worried that the publicity regarding the effort would result in a backlash and harm their own efforts to rescue Jewish children. The Wagner-Rogers Bill was failing in Congress. Polls continued to show that many Americans opposed the admission of Jewish refugees, even children. In response to these concerns, representatives of the Labor Department’s Children’s Bureau traveled to Collegeville. The Children’s Bureau confirmed the children were well-cared for.

By the end of the summer, Gilbert Kraus had found foster families or relatives to take the children. Sadly, one girl, Franzi Linhard, died of pneumonia while in the care of Brith Sholom.

Reuniting the Children with their Loved Ones

Many children soon reunited with their parents, most of whom successfully immigrated to the United States in late 1939 or 1940.

The Krauses became foster parents to two of the children, Robert and Johanna Braun. The Braun children stayed with the Krauses until after World War II, when they reunited with their parents.

While many of the children lost family members in the Holocaust, all eventually reunited with at least one parent.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have affected Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus’s decision to attempt to rescue Jews in Europe?

How did the US State Department assist or hinder the efforts of Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus?

What responsibilities do other nations have regarding refugees from oppressive regimes?

How can individuals contribute to or assist in the rescue of endangered citizens of other nations?