The Riegner Telegram

The Riegner telegram was a short message sent from Switzerland to the governments of Great Britain and the United States in August 1942. It ultimately led to a public announcement that Nazi German leadership planned to systematically murder European Jews.

Key Facts

-

1

In August 1942, Gerhart Riegner, who worked for the World Jewish Congress in Geneva, Switzerland, informed the US State Department and the British Foreign Office that he had information that Nazi Germany was planning to murder millions of European Jews.

-

2

The US State Department initially tried to block Riegner’s message from reaching its intended recipient in the United States.

-

3

The Riegner telegram was not the first information about mass killings to reach the Allied nations, but his message led to increased public awareness and reaction.

Reports of Persecution

Nazi Germany’s antisemitism and persecution of Jews was not a secret in the years before World War II and the Holocaust. Almost immediately after Adolf Hitler was named Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, newspapers and magazines abroad carried stories about new German laws targeting Jews, the establishment of concentration camps, and violence against Jews throughout Germany. Countries in western Europe saw an increase in German Jewish immigration, and after Germany’s annexation of Austria (Anschluss) in March 1938, countries in the western hemisphere debated the extent to which they should assist the hundreds of thousands of Jews seeking to leave Europe.

After war began with Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, citizens of the Allied and neutral nations heard about newly created ghettos in eastern Europe. American aid workers witnessed the deportation of Jews from France in 1942, and journalists informed readers that Jews in eastern Europe were being rounded up, taken out of their towns, and shot.

These news reports and eyewitness testimonies were first sprinkled amidst coverage of the worldwide economic depression in the 1930s and later wars in Europe and the Pacific. They did not result in widespread public understanding or belief that Nazi Germany was attempting to murder all European Jews. Even though Hitler vowed in a January 1939 speech that a world war would result in “the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe,” Nazi Germany’s initial goal had been to expel Jews from the Third Reich. But by mid-1941 and certainly by the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, Nazi Germany had altered its plan for Jews to total annihilation through murder.

Under the veil of war, international observers did not immediately recognize that Nazi Germany’s goal had changed. Allied intelligence collected information on the Einsatzgruppen, German SS and police mobile killing squads that ultimately murdered over one million Jews on the eastern front between June 1941 and June 1943. On September 12, 1941, British Intelligence informed Prime Minister Winston Churchill that “the [German] Police are killing all Jews that fall into their hands.” Soviet officials publicly acknowledged in January 1942 that “bloody executions were especially directed against unarmed and defenseless Jewish working people.” Both Allied and neutral diplomats wrote reports which included their suspicions that many thousands of Jews were being deported eastward to their deaths. However, even government officials had difficulty believing that a mass murder campaign of Jews by Nazi Germany was occurring. Moreover, many did not know what could be done, beyond fighting and winning the war, to stop the killing.

Gerhart Riegner

Gerhart Riegner was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1911. In April 1933, Riegner was fired from his position working for a Berlin tribunal court judge after the passage of the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, which removed Jews and “politically unreliable” elements from civil service professions. He moved to Paris, then to Geneva in 1934 for postgraduate study in international law. In Switzerland, the League of Nations hired Riegner. In this context, he met Dr. Nahum Goldmann, a founder of the World Jewish Congress, an international Zionist representative body. Riegner soon agreed to become the WJC’s representative in Switzerland.

After World War II began, Switzerland was largely surrounded by Axis-controlled territory. On behalf of the World Jewish Congress, Riegner collected intelligence through Jewish underground networks and distributed financial and material relief through these channels.

Eduard Schulte’s Information

In mid-July, SS chief Heinrich Himmler had toured the Auschwitz camp and afterward had dined at a villa owned by the Giesche mining firm. Within a few weeks, the details of Himmler’s inspection tour had reached Eduard Schulte, the German managing director of Giesche.

Secretly anti-Nazi and an informant to Polish and Swiss (and later American) intelligence, Schulte traveled to Switzerland on July 29, 1942, to pass the news of Nazi Germany’s mass murder plan to a representative of the Jewish community. He spoke with a Swiss Jewish investment banker, Isidor Koppelmann, who in turn met with Benjamin Sagalowitz, the head of the information bureau of the Association of Swiss Jewish Communities. Sagalowitz then contacted Gerhart Riegner, who, through the World Jewish Congress, had close contacts in London and New York. Though Riegner knew the information had come from Schulte, he vowed to keep Schulte’s identity secret, and succeeded in doing so. It was not until 1983 that historians finally confirmed Schulte’s role in publicizing the extermination plan.

The Riegner Telegram

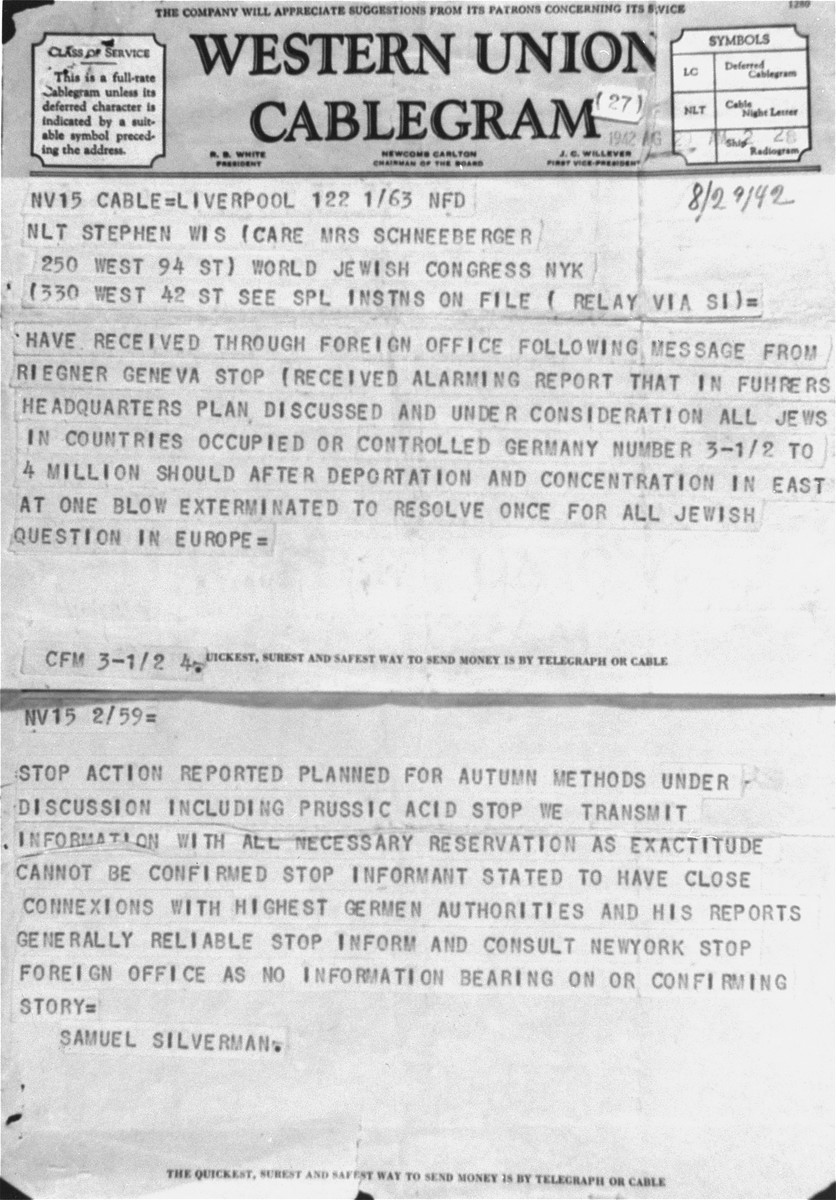

On August 8, 1942, Gerhart Riegner, who had spent the previous few days pondering the information he had received from Sagalowitz, visited the American consulate in Geneva, which reported that he arrived “in great agitation.” That day, he dictated a telegram to American vice-consul Howard Elting, Jr. Riegner’s telegram explained that between three and a half and four million Jews in Nazi-occupied territory “should after deportation and concentration in east [be] at one blow exterminated in order to resolve once [and] for all Jewish question in Europe.” Unaware that mass murder was already taking place, Riegner told Elting that the campaign was planned for the fall, and that the Nazis were considering the use of prussic acid [likely a reference to Zyklon B] to gas Jews.

Elting forwarded the message to the American legation in Bern, adding that Riegner’s information “may well contain an element of truth.” Minister Leland Harrison, the highest ranking US diplomat in Switzerland, did not believe Riegner, writing that a mass murder plan was likely a “war rumor inspired by fear.” Still, he forwarded the message to the State Department in Washington, DC.

State Department officials in Washington agreed with Minister Harrison, assuming that Riegner’s news could not possibly be true. They decided not to forward Riegner’s message to its intended recipient: Rabbi Stephen Wise, the president of the World Jewish Congress and its American component, the American Jewish Congress.

Gerhart Riegner also visited the British consulate in Geneva. He dictated a similar message to diplomatic officials there, who forwarded it to London. The World Jewish Congress representative in England, Samuel Sydney Silverman, was a member of Parliament. Though Foreign Office officials debated whether to forward the message to Silverman since it might have “embarrassing repercussions” if the public learned the news, they ultimately decided to do so. Riegner requested that Silverman “consult New York.” Silverman, therefore, sent a copy of Riegner’s message directly to Rabbi Wise, which arrived on Saturday, August 29th, three weeks after Riegner met with Elting in Geneva.

State Department Investigation

Stephen Wise was one of the most influential rabbis in the United States. When he received Silverman’s telegram, he sent a copy of the message to Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles, who agreed to investigate Riegner’s information. Welles also asked Rabbi Wise not to publicize the news until it could be confirmed by the State Department. While awaiting the conclusion of Welles’ investigation, Wise shared the information with other leaders of the Jewish community and US government officials, but didn’t make a public announcement.

From early September to late November 1942, Welles solicited evidence and testimonials from American diplomatic personnel in Switzerland, the International Red Cross, and the Vatican. Ultimately, the evidence convinced him that Riegner’s news must be true. On November 24, 1942, Welles invited Wise to the State Department and, according to Wise, confided that the evidence did “confirm and justify your deepest fears.”

Public Announcement

Stephen Wise spoke with an Associated Press reporter after his meeting with Sumner Welles at the State Department. According to Rabbi Wise, Welles told him that the State Department would not publicize Nazi Germany’s murderous plan, but he gave Wise permission to inform the press.

On November 25, 1942, newspapers throughout the United States reported variations of the report, though most placed the story on the inside pages rather than the front page. These articles explained that Nazi Germany was planning a mass murder campaign, and that it had already killed two million Jews. Some additional details, which Wise had gathered over the previous months while he waited on the State Department, including the processing of corpses into fertilizer and soap, are now known to have been false.

In response to the news, the Jewish communities in many Allied nations held rallies and vigils, and declared Wednesday, December 2, 1942, to be an international day of mourning. Thousands of workers in Ecuador paused for fifteen minutes as a gesture of protest. Some Hebrew-language newspapers added black borders to their covers. Jewish communities in Palestine, Egypt, Australia, Nicaragua, and many other countries fasted, closing their businesses for the day. Services were held in over 1,500 synagogues in the United States, and thousands of Jews joined a somber parade down the streets of New York City.

Declaration on Atrocities

State Department staff were hesitant to confirm Wise’s announcement, and complained internally about the publicity. Yet this public pressure led the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and nine Allied governments-in-exile to release a “Declaration on Atrocities” on December 17, 1942. This statement condemned the “bloody cruelties” and “cold-blooded extermination” of the Jews and vowed that the Allies would punish war criminals after the fighting stopped. The declaration did not promise Allied rescue. American and British troops had begun fighting only one month before in North Africa, and were very far from killing centers in German-occupied Poland, where most of the mass killing was taking place.

Conclusion

The Riegner telegram was not the first information about the murder of the Jews to reach the Allies. Stephen Wise’s announcement of Riegner’s message, however, resulted in widespread public outrage. After November 1942, many Allied citizens knew that Nazi Germany had a plan to murder European Jews.