How did leaders, diplomats, and citizens around the world respond to the events of the Holocaust?

Examining responses to events of the 1930s and 1940s raises questions about responsibility to intervene in the face of knowledge of persecution or genocide in another country.

Explore this question to learn about the responses of leaders and citizens, as well as the motivating factors and pressures that influenced them.

See related articles for background information related to this discussion.

After Adolf Hitler took power in Germany in 1933, the foreign press and diplomats of the United States and other countries stationed there covered Nazi Germany extensively, including reports about sporadic violence against Jews and other disturbing developments. In 1933, news articles and official briefings covered events such as the boycott of Jewish businesses, the opening of the Dachau concentration camp, and book burnings. They also covered the Nuremberg Race Laws when the Nazis proclaimed them in September 1935. In the United States, ordinary citizens could read about these events in their local newspapers, including in some front-page stories.

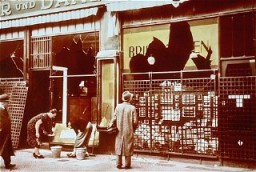

In 1938, news about two events in Nazi Germany reached the international community. Nazi terror against Jews following the annexation of Austria (the Anschluss) in March and during the nationwide pogrom of November 9-10 (Kristallnacht) sparked international condemnation. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt recalled the US ambassador for consultation, the only foreign leader to register his country’s official protest in this way.

Responses to the Refugee Crisis: 1938–1941

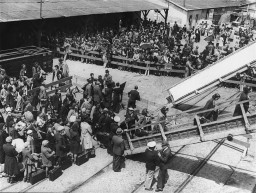

As German and Austrian Jews desperately sought safe havens abroad, most countries remained reluctant to open their doors. The leaders of most countries feared that an influx of Jewish refugees would burden their economies. They also feared that a decision to assist would be met with public disapproval due to xenophobia and antisemitism.

In July 1938, representatives of 32 countries met in Evian, France to discuss Jewish refugees. Those present condemned Nazi aggression towards Jews, but few acted to accept more refugees. The meeting became a symbol of the international failure to respond to the refugee crisis. The headline of the Nazi party newspaper (Völkischer Beobachter—People’s Observer) exulted: “Nobody wants them.”

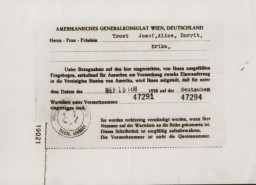

The preferred destinations for Jewish refugees were the British mandate of Palestine and the United States. In May 1939, a British “White Paper” (government report) severely limited the number of Jewish immigrants to Palestine. In the United States, restrictive quota laws and visa requirements, set in 1924, remained in place. These requirements worked together to limit the number of Jewish immigrants. For example, refugee seekers had to prove they had the resources or find an American financial sponsor. In many other countries, officials were alarmed by the influx of foreign immigrants, especially Jews. In the fall of 1938, Swiss authorities obtained German agreement to stamp the passports of Jews with the letter “J.” This stamp made Jews more easily identifiable at border crossings.

After the war began in September 1939, immigration to western countries became even more difficult. In Great Britain and France, some German refugees, including Jews, were interned as foreign aliens. In the United States, Americans feared Nazi spies and saboteurs disguised as refugees, leading to the rejection of any applicant whom the US government found questionable. Some refugees found safe havens in Shanghai, China, and in certain countries of Latin America and Africa. After October 1941, Jewish emigration from territories under Nazi control was not permitted.

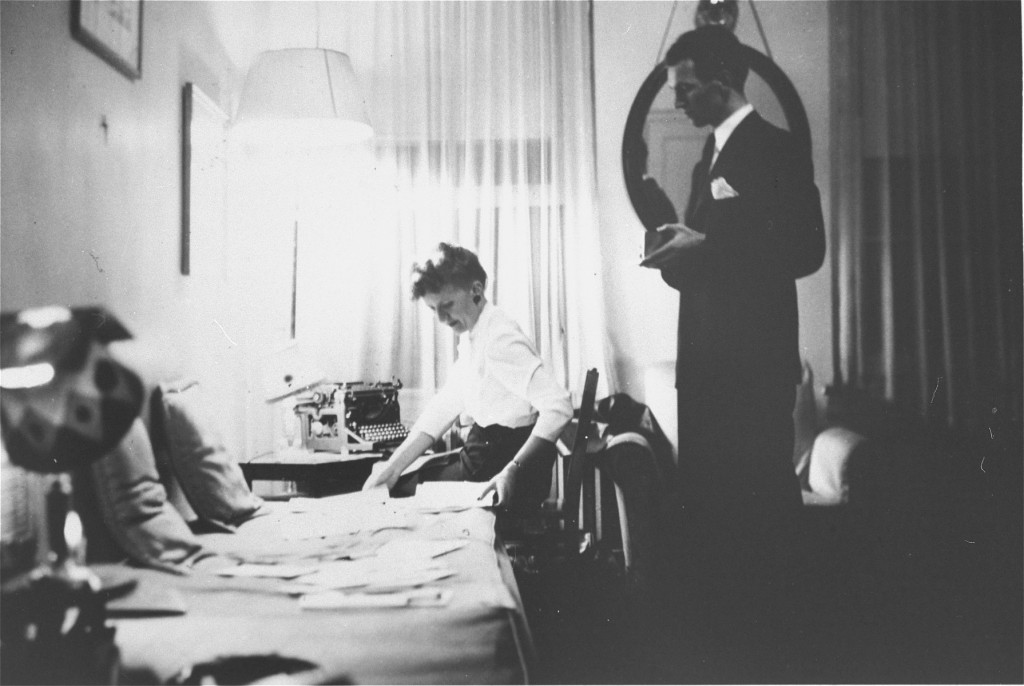

A small number of Americans overcame enormous challenges to aid Jewish refugees. Most worked within networks of religious or humanitarian organizations. They used both legal and illegal means. They often jeopardized their own safety by venturing into areas of Europe that Nazi Germany controlled or occupied. Their efforts helped thousands of Jews survive.

Responses of Leaders to the Mass Murder of Jews

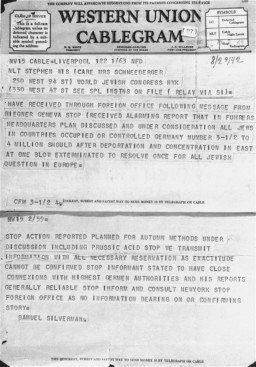

During the war, leaders of the Allied countries—the Soviet Union, United States, and Great Britain—received reports of mass shootings of Jewish civilians, including women and children. In 1942, they learned of the Nazi plan to annihilate Europe’s Jews. While leaders occasionally publicly denounced violence towards Jews, they prioritized winning the war over rescuing Jews.

Some rescue efforts by Allied and neutral governments came late in the war, after the vast majority of Jews had been killed. In 1944, the combined efforts of diplomats from neutral countries, the International Red Cross, and the Vatican, with US government support, helped protect tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest, Hungary. Five million Jews had been killed by this point.

Some citizens of European countries hid Jews on their own or worked with non-governmental organizations to rescue Jews. Some American citizens and organizations also became involved in these efforts.

Awareness of Ordinary People about the Mass Murder of Jews

The extent of awareness of the Nazi-organized mass murder of Jews among ordinary people depended on a number of factors. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) had millions of listeners across Europe, but it carried only sporadic reports of the mass murders of Jews. In 1943, news trickled out to the US public about the mass murder of Jews. Various news sources reported some details incorrectly. Additionally, there was very little visual evidence of the crimes to print. Yet the crux of the story—that Jews throughout German-occupied and -allied Europe were being deported and murdered in killing centers—was available to the American public.

Photographs, films, and radio broadcasts by journalists who reported from liberated camps such as Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen at the end of the war brought graphic details of the horror of Nazi atrocities home to the world.

Critical Thinking Questions

Consider if and how politicians and citizens prioritize problems on the home front over aiding endangered populations in other countries.

What pressures and motivations at home and abroad drive support or resistance to immigration, or even refugee rescue, in your country?

How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity?