Antisemitism and Henry Ford’s “The International Jew”

Henry Ford (1863–1947) was the founder of Ford Motor Company. He was one of the most respected and innovative business leaders in American history. Ford used his position and wealth to promote hatred of Jews. He owned an influential newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, that spread antisemitic ideas to American readers.

Key Facts

-

1

American automaker Henry Ford used mass media to spread lies about Jews to hundreds of thousands of American readers. In 1920, Ford’s newspaper began publishing a series of articles called “The International Jew.”

-

2

“The International Jew” drew on longstanding, false conspiracy theories that began outside the United States. The series presented these antisemitic ideas in ways that were intended to appeal to American readers.

-

3

Ford also influenced readers beyond the United States. In Germany, Adolf Hitler and other Nazi Party leaders admired Henry Ford for his antisemitism.

Antisemitism is prejudice against or hatred of Jewish people. It has existed for thousands of years. It has also existed in many parts of the world, including the United States. This article is about Henry Ford, one of America’s most influential business leaders. Ford used his fame and fortune to promote antisemitism in the United States. He also was admired by some Nazi leaders, including Adolf Hitler.

As the founder of Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford was one of the most respected business leaders in American history. His innovations, such as the moving assembly line, revolutionized the production of automobiles and many other products. In addition to running a successful car company, Ford owned an influential newspaper, The Dearborn Independent. He used the newspaper to spread conspiratorial lies about Jewish power over world politics, economics, the media, and other parts of society.

Henry Ford left a complicated legacy, full of contradictions. Ford was a trailblazer who redefined industrial production. Yet, even as his innovations transformed American manufacturing, Ford idealized small-town, rural life. He blamed immigrants, especially Jewish immigrants, for the problems he associated with cities and with immigrant populations. At the same time, Ford was a pacifist who hoped the United States would stay out of world wars. Despite his pacifism, the militaristic Nazis admired him for his antisemitism.

Henry Ford’s Antisemitism

Ford often privately shared his dislike for Jews with colleagues. In 1920, he began to promote hateful ideas about Jews to public audiences. One of the main outlets Ford used to spread his message was his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent. Under Ford’s ownership, the newspaper printed many false accusations against Jews. The newspaper advanced conspiracy theories about Jewish control of the United States and the world. Despite being challenged for his many lies about Jews, Ford played a significant role in spreading misinformation and antisemitism. His newspaper eventually reached hundreds of thousands of readers.

During the era of Ford’s greatest fame, antisemitism was on the rise in the United States. Historically, Jews often have been accused of controlling politics and the world economy for their own advantage. During the 1920s, lies also took hold in the United States about Jews manipulating the media for their own advantage; promoting vice and crime; and undermining morality by producing movies, jazz music, and comic books.

Conspiratorial thinking in the United States and Europe was popular during this time, especially after the Russian Revolution of 1917. Some Americans were particularly concerned that Communists and radicals might infiltrate the United States. Antisemites strongly associated Jews with radicalism. They also blamed Jews for the spread of communism.

Henry Ford shared these hateful beliefs about Jews. Throughout his life, he used his power as one of the world’s top businessmen to spread antisemitism.

Blaming Jews for World War

Henry Ford expressed his antisemitism more intensely following an ill-fated peace mission that he organized during World War I (1914–18). In 1915, he chartered a ship to sail to Europe with a number of prominent peace activists. Ford hoped that the publicity around the “Peace Ship” would lead warring nations to negotiate a peace treaty. The mission was a total failure. The press mocked Ford and called the mission a “Ship of Fools.”

After the Peace Ship embarrassment, Ford blamed Jews for starting World War I and for standing in the way of peace efforts. This lie drew on long-held, false accusations about Jews plotting to control the world, starting wars and revolutions, and manipulating the economy to their own advantage.

Claiming Jews Control the Media

In 1918, Ford lost an election for US Senator in Michigan. He blamed Jews and the media for his defeat.

After his political defeat, Ford’s contempt for the press intensified. He decided to shape news coverage by owning his own media outlet. The year he lost the election, Ford purchased The Dearborn Independent, a weekly newspaper based in Dearborn, Michigan.

Expressing Ford's disdain for other newspapers, The Dearborn Independent promoted itself as the "Chronicler of the Neglected Truth." The newspaper began running a weekly column called “Mr. Ford’s Page.” This feature was ghostwritten by reporter William J. Cameron. “Mr. Ford’s Page” promoted Ford’s vision for America and the world. Ford’s vision included the assertion that members of some ethnic and racial groups should not be allowed to immigrate to the United States. The column also accused Jews of radicalism and spreading communism.

Promoting Antisemitic Conspiracy Theories

During the first years of Ford’s ownership, The Dearborn Independent lost money. To help increase readership, Ford made a policy that everyone who bought a Model T car from the Ford Motor Company would automatically subscribe to The Dearborn Independent.

Despite attempts to make the newspaper more profitable, Ford continued to lose money on it. In 1920, he began to publish a series of antisemitic articles called “The International Jew.” This series was intended to increase profits and spread his antisemitic ideas to the newspaper’s readers. When his editor, Edwin Gustav Pipp, resigned in protest, Ford replaced him with William J. Cameron. Cameron eventually would write most of the articles in “The International Jew” series. Cameron was a rabid antisemite. He would try to shield Ford from public criticism of the articles.

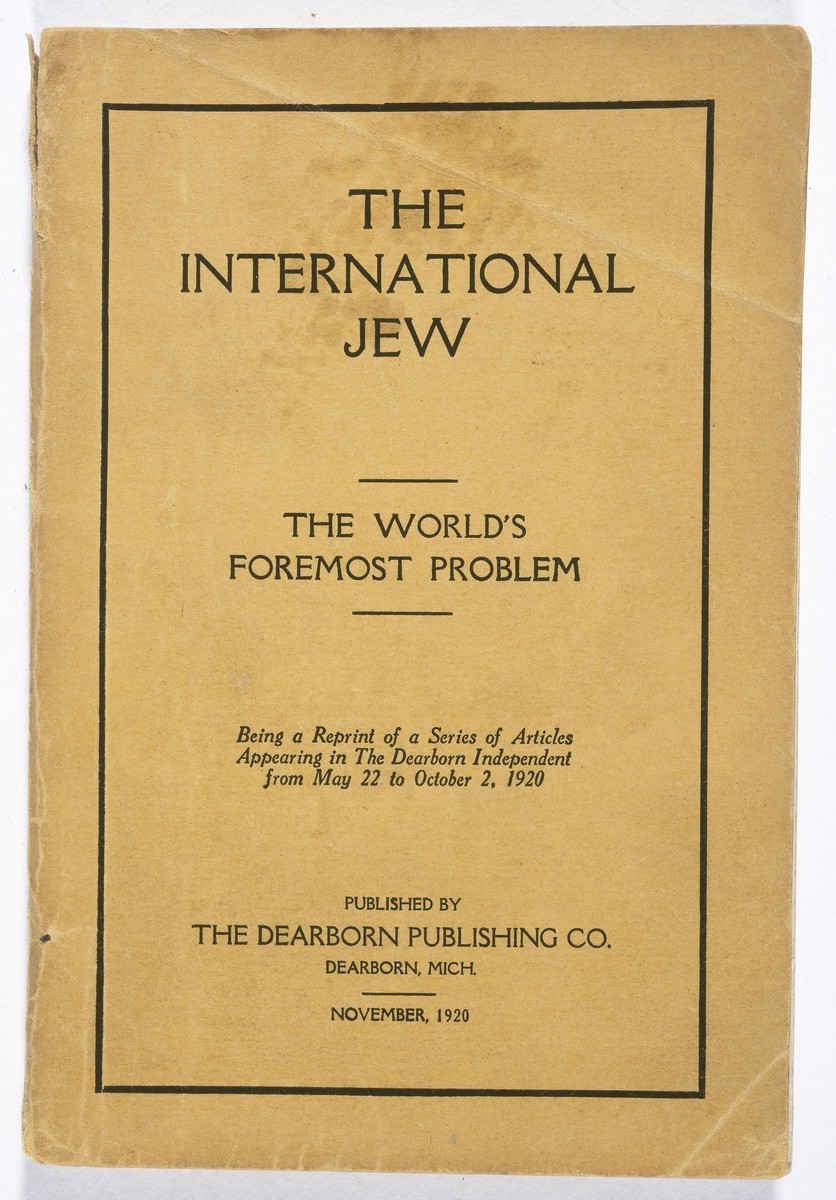

The first installment of The Dearborn Independent’s antisemitic series was published on May 22, 1920. It led with the banner headline: “The International Jew: The World’s Problem.” The article was filled with antisemitic conspiracy theories. It asked readers to consider how Jews, who made up only 3 percent of the US population, came to be in a position of “control.” Ford’s paper answered that Jews secretly manipulated governments and financial markets. It also claimed that Jews collectively acted in the best interests of their own people instead of in the best interests of the countries in which they lived.

“The International Jew” and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

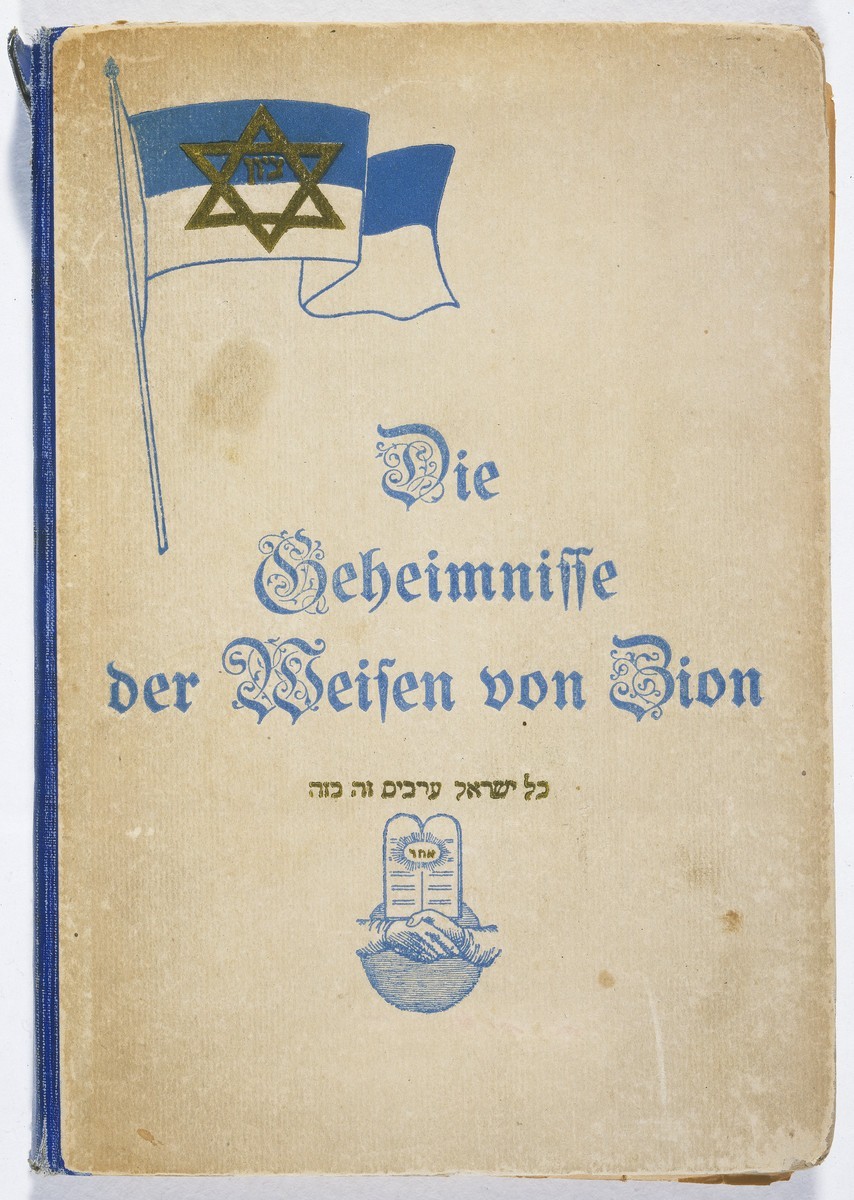

The first article in “The International Jew” drew directly on ideas from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The Protocols is a fraudulent, influential book that brings together many antisemitic ideas and conspiracy theories in a single source. By the 1920s, this book was circulating throughout the world in multiple languages. Ford learned about the Protocols in June 1920 when his business secretary, Ernest G. Liebold, received a copy.

Antisemitic lies from the Protocols made their way into many of The Dearborn Independent’s articles. The July 24, 1920, issue included an article titled “An Introduction to the ‘Jewish Protocols.’” It warned readers that the Jewish plan to control the world “is being steadily carried out.” Ford’s paper also dismissed claims that the Protocols was a forgery. It encouraged readers to distrust anyone who said that the Protocols was a fake.

“The International Jew” included articles that criticized contemporary American life in the 1920s. The articles merged antisemitic ideas from the Protocols with antisemitic accusations about supposed Jewish control of American banks, businesses, agriculture, journalism, and even baseball. Headlines from The Dearborn Independent included:

- “Jewish Control of the American Press” – September 11, 1920

- “Jewish Dictatorship of the United States During War” – December 4, 1920

- “Jewish Hot-Beds of Bolshevism in the U.S.” – April 16, 1921

- “Will Jewish Zionism Bring Armageddon?” – May 28, 1921

- “How Jews Degraded Baseball” – September 10, 1921

With these weekly articles, and many others, Ford’s newspaper became one of the most influential press outlets in the United States for misinformation about Jews.

Circulation of “The International Jew”

The Dearborn Independent’s circulation rose by hundreds of thousands of readers after it began running “The International Jew” series. In addition to printing the series, Ford took other measures to ensure that his paper would be read widely. Thousands of free copies were delivered to local clergy and community organizations. Ford auto dealerships were required to distribute copies of The Dearborn Independent as well. Some readers sent in monetary donations and praised Ford for attacking Jews.

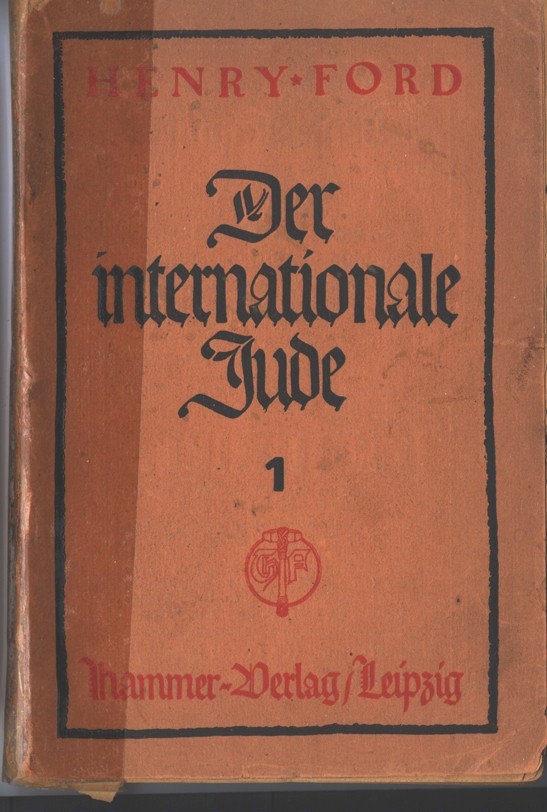

The Dearborn Publishing Company reissued this series of articles as four individual books. The books were titled The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problems (vol. 1); Jewish Activities in the United States (vol. 2); Jewish Influences in American Life (vol. 3); and Aspects of Jewish Power in the United States (vol. 4). These books were soon translated into more than a dozen languages.

Responses to “The International Jew”

Although the series was well received by many American readers, some organizations denounced “The International Jew.” The Federal Council of Churches, for example, spoke out against the series. Officials in some cities suggested censoring the newspaper or removing it from public libraries. Some car dealerships cancelled their contracts with the Ford Motor Company.

Some American Jewish leaders worried that calling attention to the series or protesting it too strongly would lead to an increase in antisemitism. Others challenged Ford to prove his claims against Jews. Some Yiddish-language newspapers refused to print advertisements for Ford’s cars. And still other organizations called on Jews not to purchase cars from Ford.

Ford Suspends the Series

In January 1922, Ford ordered The Dearborn Independent to stop running “The International Jew” series. Ford did not explain why he did this. Even though Ford stopped publishing “The International Jew,” antisemitic content still appeared regularly in The Dearborn Independent.

Henry Ford Sued For Libel

In April 1924, Ford’s newspaper published multiple articles that accused Jews of conspiring to exploit American farmers. Some pieces focused on a Jewish attorney in California, Aaron Sapiro, who organized farmers’ cooperatives. The articles repeatedly claimed that Sapiro was part of a larger Jewish conspiracy to control American farmers.

In January 1925, Sapiro demanded a retraction. He accused Ford, his private secretary, the Dearborn Publishing Company, and the Ford Motor Company of libel. Ford and his associates did not retract the articles. Instead, they challenged Sapiro to take Ford to court.

The Trial

In April 1925, the case of Sapiro v. Ford opened in Detroit’s federal court. Sapiro’s libel lawsuit included 21 counts against Ford and cataloged 141 libelous statements in The Dearborn Independent. The trial began in March 1927. Ford’s lawyers tried to distance Ford from antisemitism. They denied that the articles were antisemitic. At the same time, they drew on well-known antisemitic stereotypes and made claims about Jewish conspiracies in the agricultural industry. After some controversy about the alleged bribery of a jury member, the judge declared a mistrial.

The Apology

In the weeks after the mistrial, Ford’s representatives began to look for a way to avoid another trial. Ford privately made it known that he was willing to settle out of court. Eventually, Louis Marshall, a prominent attorney and leading voice for Jewish and minority rights in the United States, drafted a statement of apology for Ford to sign.

The apology expressed Ford’s “great regret” at being seen as an “enemy” of Jewish people. In addition to signing the apology, Ford also distanced himself from The Dearborn Independent. He claimed that had he known the details of “The International Jew” series, he would have “forbidden” their circulation. As part of the apology, Ford ordered that copies of The International Jew be burned. He also ordered overseas publishers to stop publishing the book. These orders were ignored. The International Jew continued to increase in circulation globally during the 1930s.

Ford’s apology was published in multiple newspapers on July 8, 1927, but it did not run in The Dearborn Independent. Instead, the Independent published an editorial saying that Ford had played no role in publishing the articles about Sapiro.

Influence of Ford’s Antisemitism in the United States and Germany

Ford shut down The Dearborn Independent newspaper in 1927. Yet afterwards, the book version of The International Jew continued to be used to promote antisemitism in the United States and Europe, especially Germany.

In the United States

Ford’s ideas influenced the work of many antisemitic leaders in the United States. For example, Father Charles E. Coughlin drew on themes from Ford’s The International Jew. He also serialized the Protocols in his newspaper, Social Justice, in 1938. Antisemitic organizations, such as Gerald Winrod’s Defenders of the Christian Faith and William Dudley Pelley’s pro-Nazi Silver Legion of America (also known as the “Silver Shirts”), produced publications during the 1930s that drew on The International Jew book series. After World War II, the antisemitic clergyman Gerald L. K. Smith sold copies of The International Jew in bulk to help fund his Christian nationalist crusade.

In Germany

From the moment Adolf Hitler became the Nazi Party leader in the early 1920s, he praised Henry Ford. In a 1923 interview for the Chicago Tribune, Hitler said, “We look on Heinrich Ford as the leader of the growing Fascisti [Fascist] movement in America. We admire particularly his anti-Jewish policy … We just had his anti-Jewish articles translated.”

Indeed, the German translation of The International Jew reached millions in Germany during the 1920s. Six German-language printings of the book were issued between 1922 and 1924.

Hitler also praised Ford in his antisemitic political treatise, Mein Kampf (1925). He even displayed a portrait of Ford in his private office.

Adolf Hitler’s admiration for Ford continued throughout the Nazi regime’s rule (1933–1945). On Ford’s 75th birthday in 1938, Hitler sent him personal greetings. He awarded Ford the Grand Cross of the German Eagle. This honor was the highest that the German government could give to a foreign citizen.

Ford, The Ford Motor Company, and World War II

World War II began in Europe in September 1939. Henry Ford spoke out forcefully against the United States entering the conflict. As a committed pacifist, Ford sought to convince the public that both sides in the war were motivated by greed, not by any righteous cause. In 1940, Ford joined the America First Committee. The America First Committee was an antiwar organization in the United States that promoted both isolationism and antisemitism. Once the United States entered the war in December 1941, however, Ford publicly supported the war effort and issued a statement denouncing antisemitism.

In the United States, the Ford Motor Company initially had been reluctant to move to war production. However, the company radically transformed its operations under the leadership of Henry’s son, Edsel Ford, from 1919–1943. During World War II, Ford Motor Company stopped making customer cars. It used all materials—iron, plate glass, leather, rubber—for war production. The company’s efforts were critical to the Allied victory against Nazi Germany and the other Axis Powers.

At the same time, the Ford Motor Company’s German subsidiary, Ford Werke, profited from making vehicles for Nazi Germany’s war effort. There were some efforts by the American parent Ford Motor Company to run operations in Germany. Despite this, Ford Werke fell under the direct control of the Nazi government. Henry Ford had no influence at Ford Werke. During the war, Ford Werke cooperated with the Nazi government. Ford Werke used forced laborers, including prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates, in its operations. A September 1945 US Army report called Ford Werke “an arsenal of Nazism.”

Henry Ford died in 1947, two years after the end of World War II. Decades after his death, the antisemitic literature published under Ford’s name is still available in both print and digital formats. It continues to spread misinformation throughout the world.

Since Henry Ford’s death, his descendants, the Ford Motor Company, and the Ford Foundation (established by Henry and Edsel Ford in 1936) have made efforts to publicly address Ford’s antisemitism. Many of these efforts have focused on acknowledging Henry Ford’s antisemitic actions and warning about the dangers of unchecked antisemitism.