Becoming Refugees: German Jews Prepare to Emigrate from Nazi Germany

Hundreds of thousands of Jews in Germany tried to leave the Third Reich (1933–1945) to escape persecution. Nazi antisemitic policies and violence drove Jews in Germany to search for safety abroad. To leave, Jews in Germany had to secure travel tickets and visas. For those whose efforts to emigrate failed before October 1941, the consequences were often deadly.

Key Facts

-

1

Jews fleeing Nazi Germany researched places to resettle. They also navigated many immigration requirements. Some Jews even learned new trades, skills, and languages to help them start over.

-

2

More than 340,000 Jewish refugees fled Nazi Germany and Austria. They resettled in parts of Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Australia, and Africa.

-

3

In October 1941, the Nazis banned Jews from leaving the Third Reich. Nazi authorities sent those Jews who remained in Nazi German territory to ghettos, concentration camps, and killing centers.

In January 1933, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis rose to power. Jews in Germany suddenly found themselves living under a hostile, antisemitic regime.

From the start, the Nazi regime pressured Germany’s Jewish population to leave the country. The Nazi regime immediately passed discriminatory laws and organized state-sponsored violence against Jews. This made life unbearable for Germany’s Jewish population. Jews in Germany were faced with a choice: stay in Germany or start new lives abroad?

Attempting to flee the Third Reich was an all-consuming task. First, Jews had to find suitable places to resettle. Then, they had to navigate complex immigration rules. Next, they had to get visas and travel tickets. If they got that far, they would have to pack or sell their belongings. Successfully leaving Germany often depended on the timely completion of these steps.

During the Nazi period, hundreds of thousands of Jews would emigrate. The majority of those who were unable to flee were murdered in the Holocaust.

Deciding Whether to Stay or Go

Many Jews were uncertain whether the Nazis represented another wave of antisemitic fervor that might eventually die down, or a new, more dangerous threat. This was because Jews in Germany had long faced antisemitism. By the start of the Nazi era, many antisemitic stereotypes, misconceptions, and myths had already been widely accepted in Germany and other European societies.

Without the ability to foresee the Holocaust, Jews living in the Third Reich had to constantly assess how much of a threat the regime posed. Nazi policies kept evolving and changing, making it difficult to gauge this danger. Some Jews immediately left Germany, unwilling to accept the Nazis’ limitations on Jews. Others, however, hoped that the political situation at home would stabilize.

Many felt that leaving Germany was not an option due to personal or professional reasons. Jewish men worried about losing their careers. Older individuals were more reluctant to start over in far-flung places. Jewish families feared separation from one another. Furthermore, few countries at the time welcomed Jews fleeing the Third Reich.

Over time, however, Nazi anti-Jewish policies became more and more radical. It became clearer to German Jews that they were facing an increasingly violent and extremist regime. Faced with limited options, Jews seeking to flee Germany searched intensively to resettle. They then made extensive preparations to leave the country.

German Jews were often consumed by the search for safe havens during the Third Reich. For many, trying to leave the country was almost a full-time job.

Assessing Potential Destinations

Jews trying to flee Nazi Germany had to first learn which countries would let them enter. Jews studied the complex immigration laws of each prospective country and the different procedures for applying for entry. For instance, many countries only admitted certain types of agricultural workers, skilled laborers, or technicians. Other countries had strict age restrictions for new immigrants. Also, as more Jews in Nazi Germany sought refuge abroad, more countries closed their doors to them.

There were other factors that Jews considered when picking a location. For example, they might research whether or not the local Jewish communities could provide aid; what levels of antisemitism they might face; or what the political climate was like.

But as the Nazi persecution of Jews in Germany worsened, these factors became less relevant to the decision-making process. Escape to any destination not under Nazi rule became paramount.

Navigating Immigration Requirements and Travel

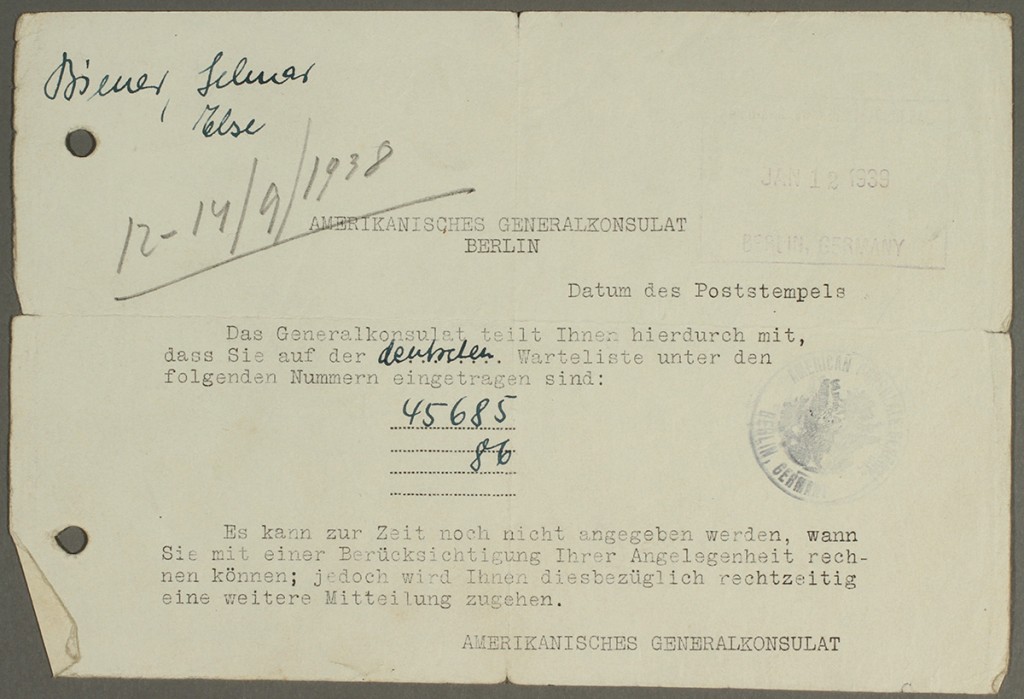

To leave Germany, Jews needed to gather a series of immigration documents. The United States, for example, required applicants to produce visas, secure sponsors, undergo medical examinations, and collect certificates of good conduct. Sometimes, Jews had to line up all day at various consulates, often with no luck. Jews living in rural areas often had to travel to the closest cities where consulates were located.

Additionally, Jews had to book their travel out of Germany, sometimes before their immigration documents were ready. They often had to compete for limited ship and train reservations. They might have worked with travel agents to book multiple legs of travel and to acquire transit visas.

The ability to successfully leave Germany usually hinged on all of these pieces falling into place in a timely manner, something that no one had full control over.

Finding Information about Destinations

To navigate these various challenges, Jews in Germany turned to many different sources of information and advice.

German Jews searched for immigration advice in multiple publications. They read pamphlets and newsletters from the Aid Organisation for German Jews. The Palestine Information Book (Das Palästina Informationsbuch) and the Philo-Atlas: Handbook for Jewish Emigration (Philo-Atlas: Handbuch für die Jüdische Auswanderung) became popular reference books as well. Such publications gave insight into politics and living conditions in various destinations.

Jews also sought help from any family, friends, or contacts in each potential destination. They sent telegrams and wrote letters. These messages were often lost in the mail. Many people experienced lengthy wait times for replies.

Information also spread by word of mouth within Jewish circles. Jewish friends and acquaintances shared firsthand knowledge about legal requirements, procedures at each consulate, and resettlement abroad.

Securing Aid

German Jews also turned to Jewish organizations in Germany. Some of these organizations gave financial assistance to Jews who could not afford the costs associated with resettlement. These costs might include train tickets or ship passage. Key sources of aid included the following organizations:

- The Reich Representation of German Jews (Reichsvertretung der deutschen Juden);

- The Relief Organization of German Jews (Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden); and

- The Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith (Centralverein deutscher Staatsburger jüdischen Glaubens).

Acquiring New Skills and Trades

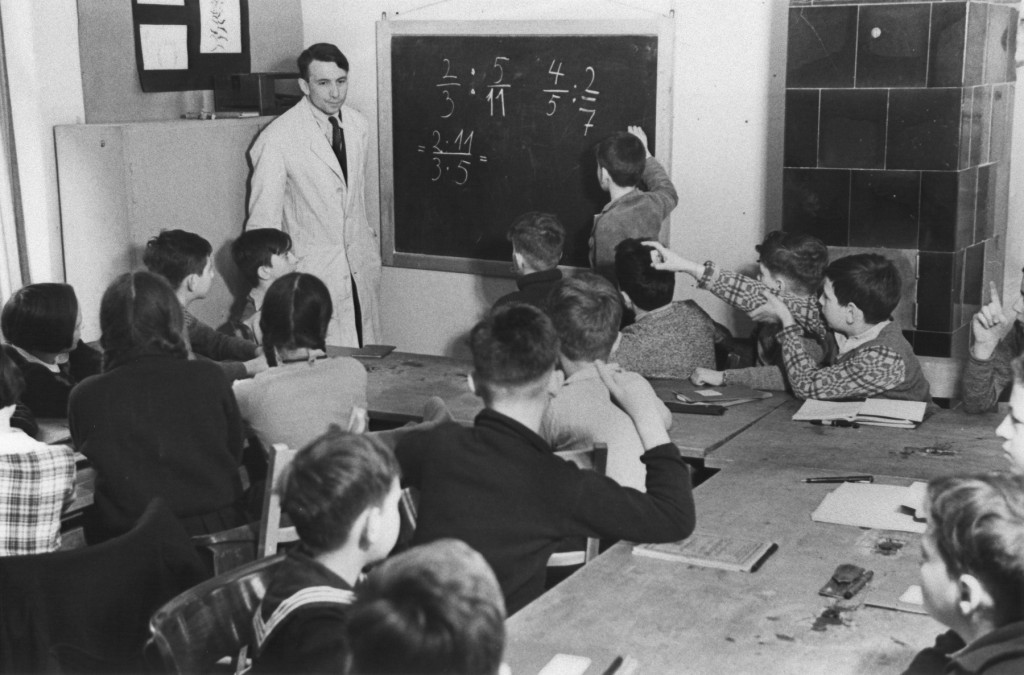

Many Jews worried about earning a living in foreign countries, especially if they did not speak the language. Some enrolled in foreign language or vocational courses to learn skills and trades that might help them start new lives abroad.

In Berlin, for example, the Jewish community offered opportunities for men to learn metalworking, woodworking, and construction. Jewish women received training in cleaning, tailoring, hairdressing, and childcare. Foreign language classes included Spanish and modern Hebrew. Jewish secondary schools introduced subjects like shop classes, stenography, and home economics to teach children useful skills. Zionists established hakhshara, or training camps, in the German countryside to encourage immigration to Mandatory Palestine. Such camps trained younger Jews in agriculture, farming, and manual trades. These camps sometimes offered modern Hebrew language courses.

Packing and Surrendering Personal Property

If a person or family could secure their papers and passage, they faced another challenge: packing and taking their belongings out of Germany.

When packing, German Jews encountered red tape at every turn. They needed permission from the German Finance Department to take anything out of the country. Officially, Jews could only leave with items they had purchased before 1933. These items were subject to Nazi approval. Nazi authorities required Jews to submit approval lists of all the items they hoped to pack. These lists included everything, such as a single handkerchief, an umbrella, or a pair of socks. Nazi authorities even supervised the packing process in person.

With so many obstacles, Jews had to make hard decisions about what to take with them. They packed clothing based on their intended destinations. Some chose things that could be used or sold abroad. Some families also tried to bring sentimental items, such as their children’s dolls or boxes of photographs.

Even when the Nazis allowed Jews to take items out of the country, Jews still had to figure out how to transport them. Shipping possessions was both costly and time-consuming. If someone had to leave the country overnight or in haste, they simply had to leave their possessions behind.

Many Jews resorted to selling their things to German neighbors at a fraction of their worth. Other Jews risked smuggling valuables that they were supposed to have surrendered to the Nazis. Many German Jews left Germany with nothing at all.

The Financial Costs of Leaving

German authorities put additional financial demands on Jews trying to escape the Third Reich. Jews had to pay a heavy emigration tax or face imprisonment for tax evasion. Furthermore, Jews were restricted from transferring their money to banks in other countries. Many Jews became penniless once they left.

Between 1933 and 1937, Jews leaving the Third Reich lost an average of 30 to 50 percent of their net worth. From 1937 to the outbreak of the war in 1939, emigration cost Jewish refugees 60 to 100 percent of their capital.

Resettling Abroad

Overall, more than 340,000 Jews emigrated from Germany and Austria during the Nazi era. Jewish refugees traveled to destinations across the globe. German Jewish refugees resettled in parts of Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Australia, and Africa.

The outbreak and course of World War II impacted many Jewish refugees. Not only did the war close off escape routes out of Europe, but many refugees also fled to regions that became embroiled in wartime conflict. For example, Jewish refugees who made it to Asia often faced Japanese occupation. Some German Jews resettled in European countries which were later occupied or annexed by the Nazis.

Remaining in Nazi Germany: The Fate of Those Who Could Not Escape

In the autumn of 1941, there were still 164,000 Jews in Germany, many of them elderly. For these Jews, the consequences of remaining on German soil were deadly. In October 1941, the Nazi regime forbade Jews from leaving the Third Reich. They began deporting German Jews to ghettos, concentration camps, and killing centers in occupied territories east of Germany. That same year, Nazi authorities began the deliberate and systematic mass murder of European Jews.

Most deported German Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.