Immigration to the United States 1933–41

Many who sought a safe haven from persecution during the 1930s and 1940s found their efforts thwarted by the United States’ restrictive immigration quotas and the complicated, demanding requirements for obtaining visas. Public opinion in the United States did not favor increased immigration, resulting in little political pressure to change immigration policies. These policies prioritized economic concerns and national security.

Key Facts

-

1

America’s restrictive immigration laws reflected the national climate of isolationism, xenophobia, antisemitism, racism, and economic insecurity after World War I.

-

2

The United States had no designated refugee policy during the Nazi period. It only had an immigration policy. Those escaping Nazi persecution had to navigate a deliberate and slow immigration process. Strict quotas limited the number of people who could immigrate each year.

-

3

Though at least 110,000 Jewish refugees escaped to the United States from Nazi-occupied territory between 1933 and 1941, hundreds of thousands more applied to immigrate and were unsuccessful.

1924 Immigration Act

In 1924, the United States Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924 (also known as the Johnson-Reed Act or the National Origins Act). It revised American immigration laws individual’s “national origins.” The act set quotas, a specific number of visas available each year for each country. The quotas, inspired in part by American proponents of eugenics, were calculated to privilege “desirable” immigrants from northern and western Europe. They limited immigrants considered less “racially desirable,” including southern and eastern European Jews. Many people born in Asia and Africa were barred from immigrating to the United States entirely on racial grounds.

The United States had no refugee policy, and American immigration laws were neither revised nor adjusted between 1933 and 1941. The Johnson-reed Act remained in place until 1965.

Potential immigrants had to apply for one of the slots designated for their country of birth, not their country of citizenship. After Great Britain, Germany had the second highest allocation of visas: 25,957 (27,370, after Roosevelt merged the German and Austrian quotas after the Anschluss). The total allowed was approximately 153,000.

The quota was the maximum number of people who could immigrate, not a target that State Department officials tried to reach. Unused quota slots did not carry into the next year.

Requirements for Immigrating to the United States

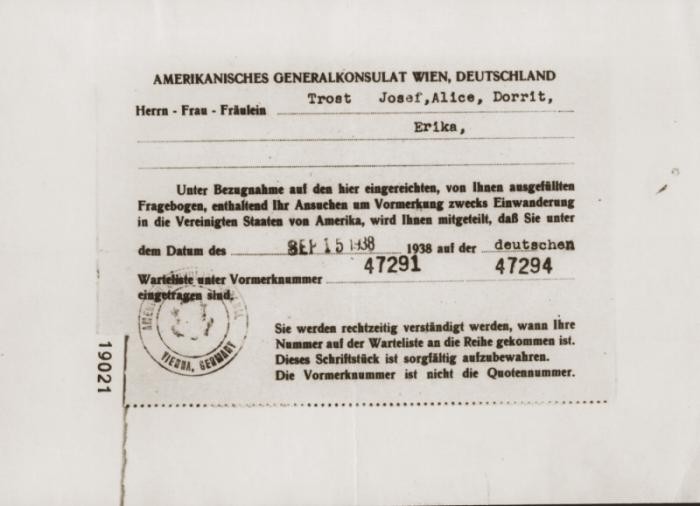

Most potential immigrants to the United States had to collect many types of documents in order to obtain an American immigration visa, to leave Germany, and to travel to a port of departure from Europe. Prospective applicants first registered with the consulate and then were placed on a waiting list. They could use this time to gather all the necessary documents needed to obtain a visa, which included identity paperwork, police certificates, exit and transit permissions, and a financial affidavit. Many of these papers—including the visa itself—had expiration dates. Everything needed to come together at the same time.

At the beginning of the Great Depression in 1930, President Herbert Hoover issued instructions banning immigrants “likely to become a public charge.” Immigration fell dramatically as a result. Though Franklin D. Roosevelt liberalized the instruction, many Americans continued to oppose immigration on economic grounds (that immigrants would “steal” jobs). Immigrants therefore, had to find an American sponsor who had the financial resources to guarantee they would not become burden on the state. For many immigrants, obtaining a financial sponsor was the most difficult part of the American visa process.

Potential immigrants also needed to have a valid ship ticket before receiving a visa. With the onset of war and the fear that German submarines would target passenger vessels, shipping across the Atlantic became extremely risky. Many passenger lines stopped entirely or at least reduced the number of vessels crossing the ocean, making it more difficult and expensive for refugees to find berths.

Waiting Lists and the Refugee Crisis

As the refugee crisis began in 1938, growing competition for a finite number of visas, affidavits, and travel options made immigration even more difficult. In June 1938, 139,163 people were on the waiting list for the German quota. One year later, in June 1939, the waiting list length had jumped to 309,782. A potential immigrant from Hungary applying in 1939 faced a nearly forty-year wait to immigrate to the United States.

In quota year 1939, the German quota was completely filled for the first time since 1930, with 27,370 people receiving visas. In quota year 1940, 27,355 people received visas. The fifteen unused visas were likely the result of a clerical error. It is difficult to estimate how many of these were refugees escaping Nazi persecution. Until 1943, “Hebrew” was a racial category in American immigration law. In 1939–1940, more than 50% of all immigrants to the United States identified themselves as Jewish, but this is likely a low number, since some refugees probably selected a different category (such as “German”) or did not consider themselves Jewish, even if the Nazis did.

Popular Opinion about Refugees in the United States

In spite of the urgency for refugees to escape, American popular opinion was against accepting more new arrivals. A Gallup poll taken on November 24–25, 1938, (two weeks after Kristallnacht) asked Americans: “Should we allow a larger number of Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the United States to live?” 72% responded “no.”

After war began in Europe in September 1939, and especially after the German invasion of Western European countries in the spring of 1940, many Americans believed that Germany and the Soviet Union were taking advantage of the masses of Jewish refugees to send spies abroad. The State Department cautioned consular officials to exercise particular care in screening applicants. In June 1941, the State Department issued a “relatives rule,” denying visas to immigrants with close family still in Nazi territory.

Aid and Assistance to Refugees

Despite public antipathy to revising American immigration laws, some private citizens and refugee aid organizations stepped in to assist the thousands attempting to flee. Jewish and Christian organizations provided money for food and clothing, transit fare, employment and financial assistance, and help finding affidavits for prospective immigrants without family in the United States. These private organizations enabled thousands to escape who otherwise would not have been able to compile their paperwork and pay for their passage.

Trapped in Nazi-Occupied Territory

On July 1, 1941, the State Department centralized all alien visa control in Washington, DC, so all applicants needed to be approved by a review committee in Washington, and needed to submit additional paperwork, including a second financial affidavit. At the same time, Nazi Germany ordered the United States to shut down its consular offices in all German-occupied territories. After July 1941, emigration from Nazi-occupied territory was virtually impossible.

Between 1938 and 1941, 123,868 self-identified Jewish refugees immigrated to the United States. Many hundreds of thousands more had applied at American consulates in Europe, but were unable to immigrate. Many of them were trapped in Nazi-occupied territory and murdered in the Holocaust.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have influenced US government officials to limit immigration levels in the 1920s and maintain those levels through the 1930s?

How did the start of World War II affect US immigration policy?

What obligations do nations have to refugees from other countries, in peace or in wartime?