"Degenerate" Art

Nazi leaders sought to control Germany not only politically, but also culturally. The regime restricted the type of art that could be produced, displayed, and sold. In 1937, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels made plans to show the public the forms of art that the regime deemed unacceptable. He organized the confiscation and exhibition of so-called “degenerate” art.

Key Facts

-

1

The Nazi regime led extensive efforts to control and shape German society and culture. It deemed a variety of modern art and artists to be sick and immoral. The regime called this art "degenerate."

-

2

In 1937, the Nazis confiscated thousands of modern artworks from German museums. They displayed many in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich.

-

3

The Nazis destroyed several thousand confiscated works of art. They sold many of the most valuable works to enrich the regime and prepare for war.

Nazification of German Culture

When the Nazi Party assumed control in 1933, its leaders began a campaign to align German politics, society, and culture with Nazi goals. This process of Nazification was widespread. The effort became known as Gleichschaltung, the German word for “coordination” or “synchronization.”

The Nazi regime disbanded organizations of every kind. It replaced these groups with state-sponsored, Nazi professional associations, student leagues, and sports and music clubs. To qualify for membership, a person had to be a politically reliable citizen and able to prove “Aryan” ancestry. All others were excluded from these groups and increasingly from the rest of German society.

In September 1933, the Nazis created the Reich Chamber of Culture. The Chamber oversaw the production of art, music, film, theater, radio, and writing in Germany. The Nazis sought to shape and control every aspect of German society. They believed that art played a critical role in defining a society’s values. In addition, the Nazis believed art could influence a nation’s development. Several top leaders became involved in official efforts on art. They sought to identify and attack “dangerous” artworks as they struggled to define what “truly German” art looked like.

Nazism and Art

The Nazis linked modern art with democracy and pacifism. Reception to modern art in Germany had varied under past governments. When Kaiser Wilhelm II ruled (1888–1918), the country had a conservative social climate. Avant-garde art was not widely appreciated. After World War I, Germany was ruled by a democratic government known as the Weimar Republic (1918–1933). The country saw a more liberal cultural atmosphere. Styles of modern art like Expressionism were more warmly received. Nazi leaders asserted that avant-garde art reflected the supposed disorder, decadence, and pacifism of Germany’s postwar democracy.

The Nazis also claimed that the ambiguity of modern art contained Jewish and Communist influences that could “endanger public security and order.” They claimed that modern art conspired to weaken German society with “cultural Bolshevism.” According to Nazi ideology, only criminal minds could be capable of creating such so-called harmful art. The Nazis called this art "degenerate." They used the term to suggest that the artists' mental, physical, and moral capacities must be in decay. At the time, "degenerate" was widely used to describe criminality, immorality, and physical and mental disabilities.

The campaign to define and control art was shaped by disagreements among leaders. Officials competed for influence within the party and government. In this case, chief Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg clashed with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. Goebbels led the Reich Chamber of Culture. As a young man, he had admired prominent avant-garde German artists. He even hoped that a form of “Nordic Expressionism” could become an official Nazi style of art. Rosenberg led a more conservative faction called the Combat League for German Culture. This effort was more aligned with Adolf Hitler’s tastes. Hitler preferred more realistic and classical styles of painting, sculpture, and architecture. Goebbels won this clash with Rosenberg by conforming to Hitler's tastes.

“Degenerate” Art Exhibitions

Within the regime's first months, some officials took it upon themselves to interpret the leadership's vague statements on art. In spring 1933, local officials began opening so-called “chambers of horrors” and “exhibitions of shame.” These efforts aimed to mock modern art. In September, a local exhibition called “Degenerate Art” opened in Dresden. The exhibition then traveled through a dozen German cities. Curators across the country removed avant-garde works from museums and placed them in storage. These initial assaults on artistic freedom were not centrally organized. As a result, Nazi definitions of "good" and "bad" art remained unclear for years.

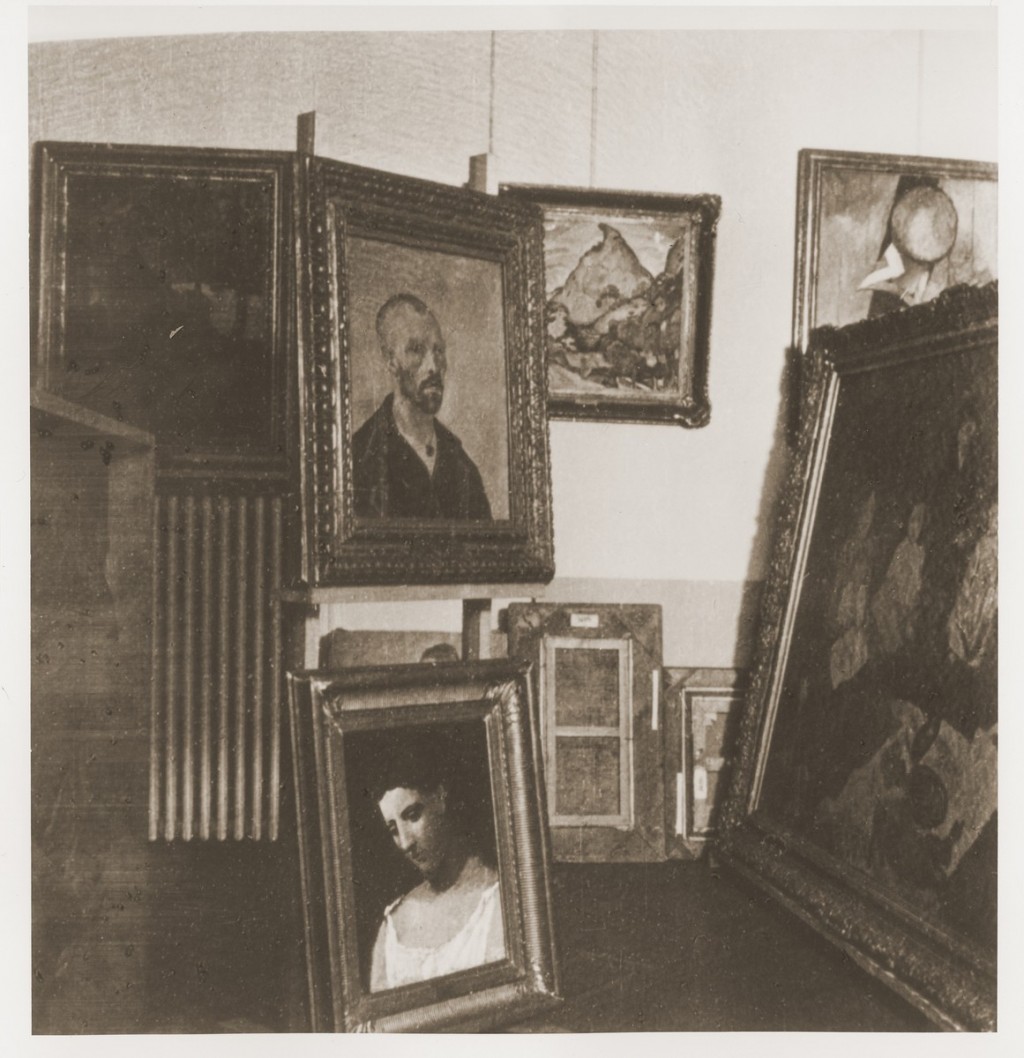

The regime attempted to clarify what “truly German art” looked like in summer 1937. The first annual Great German Art Exhibition opened in Munich at that time. Hitler reviewed selected artworks the month before it opened. He furiously ordered the removal of many examples of German avant-garde art. Goebbels witnessed this outburst and began making hasty plans for a separate exhibition. He intended to define and mock the types of art that the regime considered "degenerate." Hitler approved of the plan. The Nazis began confiscating thousands of artworks from German museums.

The “Degenerate Art” exhibition was thrown together in less than three weeks. It opened in a cramped, improvised gallery space in Munich just one day after the nearby Great German Art Exhibition. Minors were not allowed inside because of the art's supposedly harmful and corruptive nature.

The exhibition's organizers arranged more than 600 artworks in intentionally unflattering ways. They crowded sculptures and graphic works together. Paintings were suspended from the ceiling by long cords with little room between them. Many works were even left unframed and incorrectly labeled. Slogans painted on the walls mocked artworks as “crazy at any price” and “how sick minds viewed nature.” The walls also displayed quotes from Hitler and Goebbels. Their words provided the public with the official Nazi Party views on the purpose of art.

Organizers went to great lengths to discourage appreciation of the artworks. Despite this, public attendance exceeded all expectations. It is estimated that more than 2 million people passed through the cramped space in 1937. By contrast, the Great German Art Exhibition around the corner was heavily promoted and held in a spacious new building. Still, it attracted fewer than 500,000 visitors.

The "Degenerate Art" exhibition closed in Munich at the end of November. A traveling version then visited other major German cities.

Disposal of Confiscated Art

The Nazis began hastily confiscating more than 20,000 works of modern art in 1937. At that time, they made no plans for what would happen to the art. A year later, the Nazis passed a law legalizing the sale of confiscated art. They planned a large international art auction in Switzerland in June 1939. The Nazi regime profited greatly from the sale of confiscated works by famous artists like Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent van Gogh.

The Nazis assured hesitant foreign art dealers that profits would not fund Germany's ability to wage war. Publicly, they promised that all funds would go to German museums. They did not keep this pledge. The regime funneled some of its foreign profits into armaments production. In 1939, the Nazis burned more than 5,000 paintings that they could not profit from in the yard of Berlin's main firehouse.

Roughly one third of the most valuable confiscated artworks were ultimately sold to enrich the Nazi regime. Another third of the artworks disappeared. Some have reemerged over the years. With few exceptions, none of the works were returned to the museums from which they were taken. German museums have not received financial restitution. In rare cases, some art from private collections was returned to its rightful owners. Several European and American museums still possess artworks taken by the Nazis.

Critical Thinking Questions

Why were the Nazis concerned with the production and circulation of music, film, theater, radio, writing, and art? What were the Nazis trying to achieve by controlling German culture?

Why do governments censor art? Why is artistic freedom important in a society?

What role do the arts and culture play in your society?