Erika Eckstut

“I’m dreaming of a piece of bread. If I would have a piece of bread, I would be very happy.” Listen to Erika Eckstut describe life in the Czernowitz ghetto. Learn more about her experiences and the choices she was forced to make during the Holocaust.

Audio

Transcript

Bill Benson:

Tell us what life was like for you in the ghetto.

Erika Eckstut:

You know, whenever I speak, and it came to tell how was it in the ghetto, to tell you it was bad doesn’t mean nothing. It was worse than bad; I don’t have a word to use, what it was like. There was no food. There was nothing you can do. There was nothing you can eat.

It was just terrible. Outside there were signs, if you help a Jew you and your family will be killed. There were signs, children couldn’t go to school. If they find that children are learning anything they will be killed. It was terrible what was outside. What was all over that they were talking about. My father, who was so much for just the right way, you can’t take the law in your own hands, he decided that we have to learn something in the ghetto, because we didn’t have any food and we didn’t have what to do. There were professors, teachers, students—anybody could have taught us. We really didn’t know anything yet, and they started, and my father also taught us.

He told us about the French Revolution, which really didn’t interest me at all, and I didn’t pay attention. Whenever my father asked me, I never had an answer because I never paid attention. When my father was telling me that I hurt him very much by never knowing anything, I said, “I didn’t pay attention.” He says, “Why didn’t you pay attention?”

I said, “I’m dreaming of a piece of bread. If I would have a piece of bread, I would be very happy.” And my father said, “Aren’t the other children hungry too?” I said, “Maybe not as much as I am.”

Bill Benson:

Erika, so here, under those terrible conditions in the ghetto with no food, your father, who had founded the Hebrew school in your hometown, and others, were still concerned about making sure you got an education.

Erika Eckstut:

Yes. That was the most important thing.

Bill Benson:

Being the “wild duck” that you were, though, you could not be constrained for long, so you began to make forays, or sneak out of the ghetto.

Erika Eckstut:

I did.

Bill Benson:

Tell us about that.

Erika Eckstut:

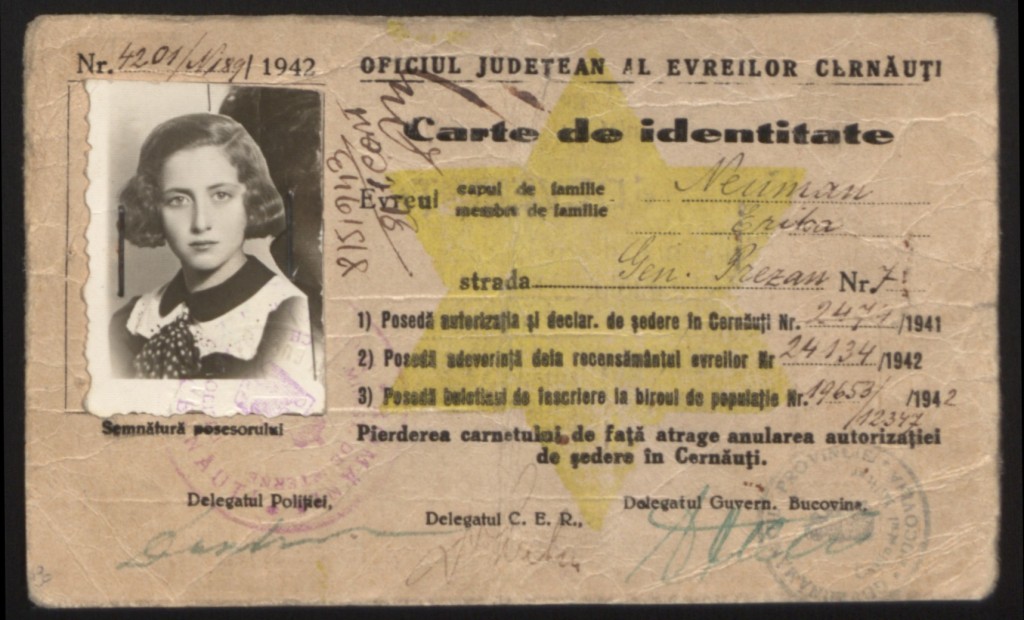

After my father told me that I hurt him very much, I really realized I did, and as you saw the thing I had, you know, the ID, and we wore the star on the coat. I took the star and I took the ID and I left it where I slept and I walked out. I wasn’t worried that anybody was going to stop me.

I was blonde (now I’m really very blonde), but I was really blonde, and I have blue eyes, and my mother’s tongue was German, so I said nothing can happen to me. I also heard my mother talk that my father had a friend when he was about seven or eight years old and the friend became a priest and I knew his name.

I forgot his name (I forgot a lot of names) but I knew it then and I went where they sold for nuns, for priests, and I took whatever I thought would be all right for us.

Bill Benson:

It was a store where they sold to priests and nuns?

Erika Eckstut:

Yes, to priests and nuns. And when it came to pay, I said, “Father So-and-so is going to pay,” and they wrote it down and asked me, “Is that the right way?” I said, “Yes,” and they gave me the food and I went back. When I came in the ghetto, my mother fainted. I couldn’t see why she fainted, but she never thought she’d ever see me again.

My father wanted to know how did I pay for the food, and when I told him that I said his friend is going to pay, my father said, “Who told you I had a friend?” I said, “I heard mother talk about it; nobody told me.” My father said, “You know, you will have to go and tell him what you did.”

I said, “All right.” So the next day I had to go to the priest, and you know, the priest was not a priest. He was like an angel. He was so nice and when I told him what I did, he says, “You have to promise me now that you will never tell anybody how you do what you do, to nobody.”

I said, “My father knows.” He said, “Don’t worry about your father. Just promise you won’t talk to anybody,” and I did [promise], because I didn’t tell anybody what and how I did.

Biography

Erika (Neuman) Eckstut was born in Znojmo, Czechoslovakia, on June 12, 1928, the younger of two girls. Her father, Ephram Neuman, was a respected attorney and an ardent Zionist who hoped to immigrate to Palestine with his family. Her mother, Dolly (Geller) Neuman, held a degree in business and worked in a bank before the birth of her children.

When Erika was a young girl, the Neumans moved to Stănești, a town in the province of Bukovina, Romania, where Erika’s paternal grandparents lived. Erika attended public school as well as the Hebrew school her father helped found. She loved to play with her sister, Beatrice, and especially enjoyed being with her grandfather.

In 1937, the fascist Iron Guard tried to remove Erika’s father from his position as the chief civil official in Stănești. Eventually, a court cleared him of the fabricated charges and he was restored to his post. In 1940, the Soviet Union annexed the area of Romania where the Neumans lived, but one year later, Germany invaded the Soviet Union and Romanian troops drove the Soviets from Stănești. Romanian soldiers and civilians carried out bloody attacks on the town’s Jews.

In the fall of 1941, the Neumans were forced to settle in the Czernowitz ghetto, where living conditions were poor and they faced constant fear of deportation to Transnistria, a large swampy region of open air ghettos and camps in Romanian-occupied Ukraine. In 1943, Erika and Beatrice escaped from the ghetto on false papers that their father had obtained through the help of a local priest.

Using the false papers and posing as Christians, Erika and Beatrice fled to Kiev, a city in Soviet Ukraine which had just been freed from German occupation. Beatrice obtained work in a hospital and Erika assisted at times. Toward the end of the war, a nurse at the hospital mistook Beatrice for a German spy and, fearing for their safety, Erika and Beatrice decided to return to Czechoslovakia.

While traveling through the Soviet Union and Poland, still using false papers identifying them as Christians, Beatrice was again mistaken for a German by a group of Russian soldiers and narrowly escaped arrest. Erika and Beatrice reached Prague and were eventually reunited with their parents, who had managed to escape Czernowitz and survive the war in Bucharest, Romania. Erika’s father died from natural causes a few years after the end of the war.

On August 28, 1945, Erika married Robert Kauder. A Czech Jew who fled his native country for the Soviet Union, Robert had been deported to a labor camp in Siberia by the Soviets. Upon his release in 1942, he joined the Svobodova Armada, a Czech battalion formed by the Czech government-in-exile to fight Nazi Germany. Robert and Erika met while she and Beatrice were on their way to Prague. After marrying in Jesenik, where Robert’s unit was stationed, the couple remained there until 1948 and then moved back to Prague, where they had two children together.

After Robert’s death in 1957, Erika began trying to immigrate to the United States and was permitted to do so in 1960. After settling in the United States, she became a supervisor of a pathology lab. She volunteered at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.