Paragraph 175 and the Nazi Campaign against Homosexuality

Paragraph 175 was a German statute that criminalized sexual relations between men. It did not criminalize sexual relations between women. Paragraph 175 predated the Nazi regime. However, the Nazis revised Paragraph 175 in 1935 to make it broader and harsher. It was one of the main tools that the Nazis used to persecute gay men and men accused of sexual relations with other men.

Key Facts

-

1

Paragraph 175 became part of the German Empire’s criminal code in 1871. This statute built on a long tradition of criminalizing and punishing sexual relations between men across Europe. It remained a part of German criminal codes in various forms until 1994.

-

2

In 1935, the Nazi regime revised Paragraph 175. The Nazi version of the statute allowed the regime to target far greater numbers of men than previous governments.

-

3

Most men arrested under Paragraph 175 were given fixed prison sentences. Some of these men, however, were sent to concentration camps for indefinite terms.

What was Paragraph 175?

Paragraph 175 was the statute of the German criminal code that banned sexual acts between men. It did not apply to sexual acts between women.

This statute was part of Section Thirteen of the German criminal code. Section Thirteen regulated “Crimes and Offenses against Morality” (Verbrechen und Vergehen wider die Sittlichkeit). Other crimes in this section included bestiality, bigamy, incest, and sexual assault.

Paragraph 175 was a statute under the German Empire (1871–1918), the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), the Nazi regime (1933–1945), and into the postwar era. However, it was enforced differently by different governments and regimes.

While Paragraph 175 criminalized sexual acts between men, it was never a crime to identify as a gay man in Germany.

Paragraph 175 before the Nazi Regime

Paragraph 175 was part of the German Empire’s criminal code, enacted in 1871. This statute built on a long tradition of criminalizing and punishing sexual relations between men across Europe. In particular, the legal principles and language in Paragraph 175 came from the 1794 and 1851 Prussian legal codes.

The 1871 version of Paragraph 175 read:

Unnatural sexual acts (widernäturliche Unzucht) committed between persons of the male sex, or by humans with animals, is punishable with imprisonment; a loss of civil rights may also be sentenced.

During both the German Empire and the Weimar Republic, the German criminal justice system interpreted “unnatural sexual acts” in a narrow way. Men could only be convicted for violating the prohibition against sexual relations between men if it could be proven they had engaged in “intercourse-like” (“beischlafsähnlich”) acts. This made it very difficult for the police and the justice system to enforce Paragraph 175. Proving that “intercourse-like” acts had occurred often required policemen to catch the individuals in the act.

As a result of the justice system interpreting the statute narrowly, statistics show that yearly convictions typically numbered in the hundreds during both the German Empire and the Weimar Republic.

Discussing Homosexuality and Paragraph 175

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the nature of human sexuality became an important area of scientific investigation and debate. Germany was at the forefront of this development, not least because of debates regarding Paragraph 175.

Advocating for the Decriminalization of Sexual Relations between Men

Even before the founding of the German Empire in 1871, there were campaigns advocating for the decriminalization of sexual relations between men in various German states. In 1869, as part of these early efforts, one German-speaking advocate for decriminalization coined the word “Homosexualität” (“homosexuality”), among other related terms.

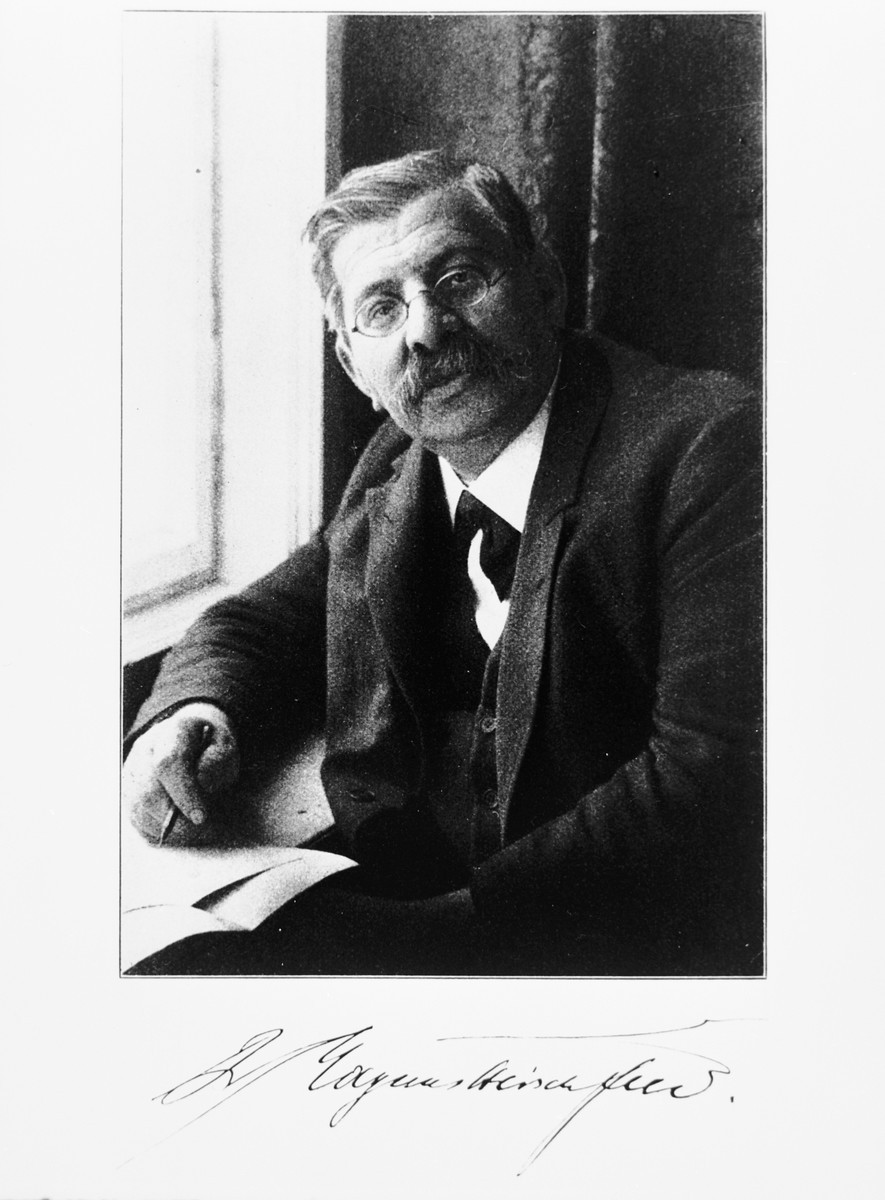

By the early twentieth century, one of the most prominent advocates was physician and sex researcher Magnus Hirschfeld. Hirschfeld challenged the common idea at the time that same-sex attraction was a pathological perversion and a vice. Instead, he argued that it was innate or inborn (angeboren). He adopted the term “homosexuality” because he thought it best communicated this idea.

Based on his understanding of same-sex attraction as inborn, Hirschfeld argued that homosexuality should not be punishable by law. In 1897, he founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee (Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee). This committee spearheaded a campaign to reform Paragraph 175. Their efforts became particularly important in the 1920s during the Weimar Republic.

Political Debates about Paragraph 175

Hirschfeld’s campaign to reform Paragraph 175 coincided with broader societal trends. During the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), there was an attempt to reform the entire German criminal code so that it better reflected the era’s understanding of the nature and causes of crime. In terms of Paragraph 175, German legal scholars and politicians debated whether sexual relations between men should be considered a crime at all.

Among the groups who supported the decriminalization of sexual relations between men were:

- the large, moderate-left Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei);

- the more radical Communist Party (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands);

- the pacifist German League for Human Rights (Deutsche Liga für Menschenrechte);

- the centrist German Democratic Party (Deutsche Demokratische Partei).

However, there were also groups who advocated for making this statute stricter. Among them were various moderate and right-wing political parties and mainstream religious organizations. For example, the radically right-wing Nazi Party officially opposed any efforts to decriminalize sexual relations between men. Wilhelm Frick, a Nazi member of the Reichstag, stated in 1927 that “men committing unnatural sexual acts with men must be persecuted with utmost severity. Such vices will lead to the disintegration of the German people.”

The political deadlock of the Weimar Republic ultimately prevented any revision of the criminal code. Paragraph 175 remained in effect.

Revising Paragraph 175 during the Nazi Regime

Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany in January 1933. In the first two and a half years of the Nazi regime, the government enforced Paragraph 175 similarly to the way it was enforced in the Weimar Republic. At this time, the Nazis also used other means to target Germany’s gay community. For example, they closed meeting places, arrested repeat offenders, and shuttered presses.

However, in 1935 the Nazi regime revised Paragraph 175. Afterwards, it began prosecuting men in far greater numbers for violating this statute.

Revision of Paragraph 175

As part of a broader Nazi effort to rewrite and reform the criminal code, Nazi jurists amended Paragraph 175 on June 28, 1935. The new version of the statute went into effect on September 1 of that year.

The Nazi version of Paragraph 175 read:

A man who commits sexual acts (Unzucht) with another man, or allows himself to be misused for sexual acts by a man, will be punished with prison.

Notably, Nazi jurists dropped the adjective “unnatural” (“widernatürliche”) from the new version. They did so because, according to their understanding, the word “unnatural” had created a problem. It had forced the criminal justice system to define the crime too narrowly as “intercourse-like” (“beischlafsähnlich”) acts. Removing the term “unnatural” made the statute more vague and allowed for a broader interpretation of the phrase “sexual acts.” Consequently, a wide range of intimate and sexual behaviors could be, and were, punished as criminal. This even included gestures as simple as looking at or touching another man.

As before, however, neither Paragraph 175 nor any other statute ever criminalized identifying as a gay man. Nonetheless, the revision of Paragraph 175 broadly expanded the type of acts subject to punishment. Thus, it dramatically increased the number of men punished under the statute.

Sections 175a and 175b

The new version of Paragraph 175 had two additional sections: 175a and 175b.

Section 175a listed four specific behaviors that the Nazis saw as particularly egregious violations of Paragraph 175. These included a man

- coercing another man to have sex;

- initiating sexual relations with a male subordinate or employee;

- having sexual relations with a male minor (under the age of 21);

- engaging in prostitution with another man.

The Nazi regime saw men who engaged in these behaviors as particularly harmful, because they believed that they were corrupting other men. According to 175a, these acts could result in a sentence of up to ten years hard labor in a prison. Within the context of the German criminal justice system, this was a comparatively long and harsh prison sentence.

Importantly, both parties could be punished. For analogous heterosexual acts, only the person who instigated the act could be penalized. Furthermore, the legally proscribed sentences for analogous heterosexual acts were shorter.

Section 175b became the statute banning bestiality. As before, this prohibition applied to both men and women.

Paragraph 175 and Sexual Relations between Women

When reforming the statute in 1935, Nazi jurists had a chance to extend Paragraph 175 to women. However, they chose not to do so. Nazi leaders saw lesbians as women who had a responsibility to give birth to racially pure Germans, called “Aryans.” The Nazis concluded that Aryan lesbians could easily be persuaded or forced to bear children. Their beliefs drew on widespread attitudes about the differences between male and female sexuality. Furthermore, women did not typically hold leadership roles in the military, economy, or national politics. Therefore, the Nazis did not view lesbians or sexual relations between women as a direct threat to the German state.

Women who identified as lesbians were sometimes charged under other statutes, such as the ban on sexual relations with a minor.

Enforcing Paragraph 175

By the end of 1936, SS leader and Chief of the German Police Heinrich Himmler had taken the lead in cracking down on homosexuality, which he called a “public scourge.” He directed the police forces under his control to enforce Paragraph 175. Himmler believed that this was necessary for the protection and strengthening of the German people.

In 1936, Himmler established the Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion (Reichszentrale zur Bekämpfung der Homosexualität und der Abtreibung). This office was part of the Kripo (Criminal Police) and worked closely with the Gestapo (political police). One of its main responsibilities was to police and track down men suspected of homosexuality.

Under Himmler’s direction, these police forces diligently pursued violations of Paragraph 175. They conducted targeted raids on locales popular with gay men and closely monitored Germany’s gay communities.

Paragraph 175 Arrest Numbers

Scholars estimate that there were approximately 100,000 arrests for violations of Paragraph 175 during the Nazi regime. Over half of these arrests (approximately 53,400) resulted in convictions. However, it is important to note that these numbers do not tell us the total number of individual men arrested and convicted for violating Paragraph 175. This is because some men were arrested and convicted—and thus counted in these statistics—more than once.

Statistics from the 1930s show that Nazi policies had a significant impact on the number of men convicted under Paragraph 175. This is most noticeable when we look at conviction numbers from before and after the 1935 revision of the statute:

- In 1934, there were 948 convictions for violating Paragraph 175. This number is comparable to conviction rates during the Weimar Republic, albeit on the high end.

- In 1936, there were 5,320 convictions.

- In 1938, the number of convictions increased to approximately 8,500.

Data about arrests and convictions for violations of Paragraph 175 during World War II (1939–1945) is incomplete.

In most cases, men accused of violating Paragraph 175 were sentenced by ordinary courts to a fixed prison sentence. Most of them were not sent to concentration camps.

“Transvestites” (“Transvestiten”) and Paragraph 175 Arrests

Not everyone arrested under Paragraph 175 identified as a man. During the German Empire and the Weimar Republic, Germany was home to a developing community of people who identified as “transvestites.” Magnus Hirschfeld coined the term “transvestite” (“Transvestit”) in 1910. Initially, this term encompassed people who performed in drag, people who cross-dressed for pleasure, as well as those who today might identify as trans or transgender. Today, in English, the term “transvestite” is outdated and offensive. However, it was widely used at the time.

Some self-identified transvestites were arrested under Paragraph 175. These were people who were assigned male sex at birth, but identified—and often dressed and lived—as women. When they engaged in sexual relations with men, the Nazi regime saw this as male-male sex. But, many transvestites did not see themselves as “homosexual” (“homosexuell”). They did not consider their sexual relations with men as male-male sex. Nonetheless, they were punished according to the regime’s definition.

Paragraph 175 Prisoners in the Concentration Camps

Most men arrested under Paragraph 175 were given fixed prison sentences. There were, however, some men sent to concentration camps for indefinite terms. Scholars estimate that this group numbered between 5,000 and 15,000 men. The Gestapo and the Kripo both had the power to send men accused of homosexuality to concentration camps. Gestapo prisoners were held under “protective custody” (Schutzhaft). Kripo prisoners were held under “preventive detention” (Vorbeugungshaft).

Why were some men sent to camps?

Many of the men that the Nazi regime sent to the concentration camps as “homosexual” (“homosexuell”) were considered repeat offenders (Gewohnheitsverbrecher). They had multiple convictions for violating Paragraph 175. Nazi leaders, including Himmler, believed that these men were particularly dangerous. Himmler believed they could and would seduce heterosexual men. This would decrease the German birth rate and weaken the nation.

The Pink Triangle

The Nazis classified prisoners in concentration camps into groups according to the reason for their imprisonment. By 1938, these groups were identified with various colored badges worn on camp uniforms. Many men imprisoned for allegedly violating Paragraph 175 had to wear a pink triangle. This badge identified them as “homosexual” (homosexuell) according to the prisoner classification system. Sometimes these prisoners were called “175ers.”

Pink triangle prisoners suffered enormous abuse in concentration camps. They often found themselves near the bottom of the camp hierarchy, where they were subject to abuse from other prisoners and from the SS guards. Nonetheless, a few well-educated men imprisoned as homosexuals managed to secure jobs within the camp administration. Holding such a position helped many of these prisoners survive. In general, however, research suggests that “homosexual” prisoners had a very low chance of survival.

Paragraph 175 after the Nazi Era

The criminalization of sexual relations between men in Germany did not end with the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945. After World War II, Germany was remade by the Allied Powers. It became two countries in 1949. These countries were on opposite sides of the Cold War.

- The Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) had a liberal-democratic constitution and was aligned with the United States.

- The German Democratic Republic (East Germany) was a communist state and aligned with the Soviet Union.

After the war, the Allied Powers forced the Germans to repeal Nazi statutes and laws. However, even though the Nazis had revised Paragraph 175, the Allies allowed the revised version to remain in effect. This was because the statute had been part of the German criminal code before the Nazi era. East and West Germany used different versions of this statute.

Within one year of its founding, East Germany chose to use the earlier, narrower version of Paragraph 175. This version used the wording from 1871. The country also kept Paragraph 175a, which criminalized certain non-consensual sexual acts between men. In 1957, East Germany stopped enforcing Paragraph 175. It fully abolished both statutes in 1968.

West Germany continued to use the 1935 Nazi version of Paragraph 175 (including 175a and 175b). At first, West German authorities vigorously enforced the statute. Between 1949 and 1969, 100,000 men were arrested under Paragraph 175. Approximately 59,000 of them were ultimately convicted. Some of these men received prison sentences. The prison sentences were typically much shorter than during the Nazi-era. In some cases, they lasted days or weeks. Other men did not serve time, but instead had to pay a fine. In 1969, West Germany deemphasized enforcement of the statute.

Paragraph 175 was dropped from the German criminal code in 1994 after East and West Germany reunited as the Federal Republic of Germany.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

While today many members of the LGBTQ+ community consider such terms derogatory, the words “homosexuality” (“Homosexualität”), “homosexual” (“homosexuell”), and other related terms were popular and broadly used at the time. They gained acceptance among much of the German medical and scientific community. Men began to identify as “homosexual” (“homosexuell”) or same-sex oriented (“gleichgeschlechtlich”) in late nineteenth century Germany.

-

Footnote reference2.

These statistics include all convictions under Paragraph 175, including 175a and 175b.

Critical Thinking Questions

How and why did the Nazi regime target gay men and lesbians?

How did the Nazi regime’s persecution of gay men and lesbian women fit into the broader Nazi worldview?

What can other nations and people do when a civilian group is persecuted in another country?