Estelle Laughlin

"We were marched through the streets. The ground beneath us trembled. The air thundered with detonations. The buildings crumbled to our feet." Listen to Estelle Laughlin describe living through the Warsaw ghetto uprising in April 1943. Learn more about some of her experiences and the choices she was forced to make during the Holocaust.

Audio

Transcript

Estelle Laughlin:

The Jewish people began to organize themselves into an armed resistance. They started to build bunkers. As I pointed out the buildings were practically vacant, so whoever, most of the people moved to the ground floor. The resistance fighters started to build bunkers in the basements. My father was a member of the underground and we had a bunker too.

The floor in our powder room, the whole floor lifted, commode and all, and then you’d step down in, down a flimsy little ladder and you were out of sight. Well, the resistance fighters built a network of bunkers and they dug tunnels so that they can move from bunker to bunker and tunnels underneath the wall to get to the other side, to the Christian side, and hopefully obtain ammunition and arms from the Christian underground.

The real fighting began when the armored cars, tanks, brigades of soldiers, bomber planes, trucks with loudspeakers, announcing, “You better all report or else we’ll kill you.” And of course we did not obey, we bolted into our bunker. And you can imagine when we pulled the trap door closed and we stepped into this damp darkness, the ceiling closed in on us. The walls pressed me and the few people who were with me in the bunker were my whole nation. The flickering of the carbide light was the substitute for the sun. The ticking of the clock was our only connection with the universe outside, that’s how we knew when morning was rising, when the sun was setting. How abandoned I felt. How I craved for the open horizons, for the crispness, blue crispness of day.

And while we were in this bunker, the freedom fighters confronted a twentieth century army. Just a small group of poorly clad, poorly fed, poorly armed freedom fighters climbing up on rooftops, meeting the tanks on street corners, standing in front of open windows and lobbing Molotov cocktails and whatever explosives they could find. They fought so bravely, they fought for four weeks, even after the ghetto was declared cleansed of Jews the Jewish fighters were still fighting. It is really noteworthy that the Jewish resistance fighters in the Warsaw ghetto fought longer than it took for France or for Poland to capitulate. I think that is remarkable.

Well, “Boom!” there was this horrendous explosion. I thought that my head was blown off. Dust was flying, splinters were flying around me. In one instant our hiding place was invaded by a bunch of barbarians and they chased us out of the bunker. At that point there was not even a corner that we could hide in. We could not even, we didn’t even have the freedom to fall to our knees and form fists and smash the earth. We were marched through the streets. The ground beneath us trembled. The air thundered with detonations. The buildings crumbled to our feet. The flames, the flames were enormous, enormous tongues of flames licked the sky and painted it in otherworldly colors of iridescence. The smoke, towers of smoke. People lying in congealed blood. I tried to turn my face away not to see it. I couldn’t understand what death meant. All I hoped for is that I meet it with my mother, and sister, and my father. But I couldn’t turn my face away from the people who I cannot forget, and they marched us onto Umschlagplatz onto freight trains, crowded like sardines.

Biography

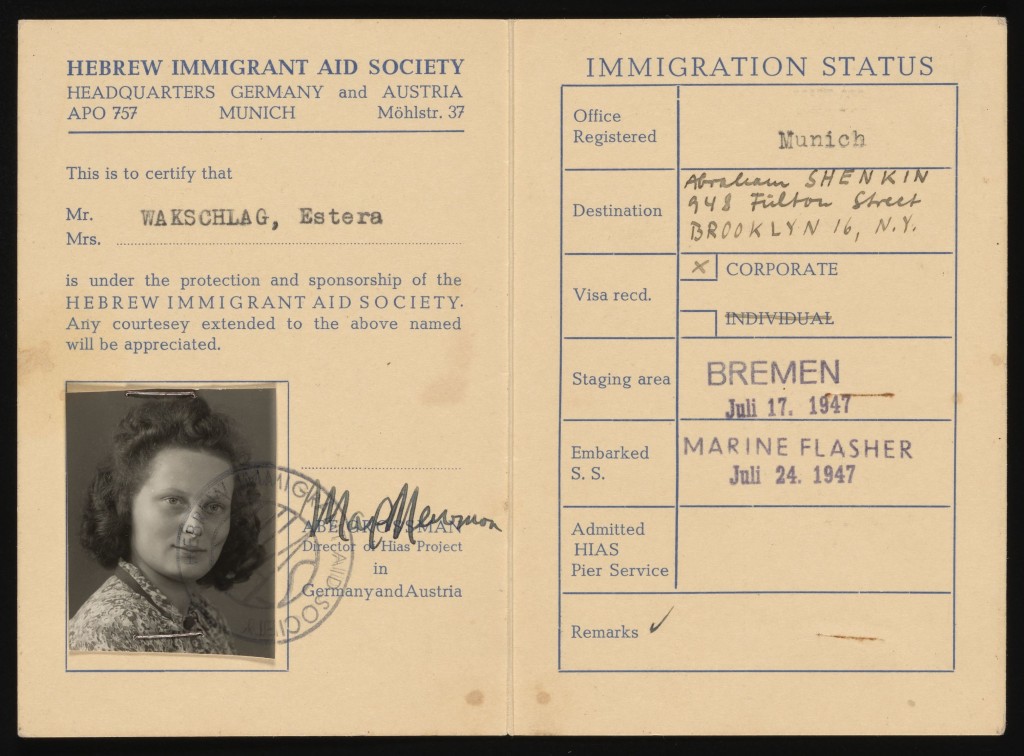

Estelle Laughlin was born Estera Wakszlak in Warsaw, Poland, on July 9, 1929 to Michla and Samek Wakszlak. Estelle had an older sister, Frieda, who was born in January 1928. Michla tended to the home and children while Samek ran a jewelry shop. Estelle and Frieda attended the local public school.

Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. The siege on Warsaw began a week later. During the siege, Estelle experienced aerial bombing raids and witnessed the mass destruction that German bombs wrought in her home city. On September 28, Polish forces in Warsaw officially surrendered, and soon after, German forces entered the city. Estelle and Frieda were no longer allowed to attend the local public school.

In October 1940, German authorities decreed the establishment of a ghetto in Warsaw. The Wakszlak family and more than 400,000 Jews from the city and surrounding areas were forced to live in a 1.3 square mile area. The family’s apartment building was on a street that became part of the ghetto so, unlike many others, they did not have to move. This helped them survive because they had access to their possessions, including warm clothes.

Still, life in the Warsaw ghetto was harsh for the Wakszlak family and the other Jews imprisoned there. They had to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David, identifying them as Jews. The food allotments rationed to the ghetto by the German authorities were not sufficient to sustain life. Starvation and disease were rampant. Samek was able to get extra food for his family from the black market. Even in the face of these horrific conditions, a cultural life continued in the ghetto. Estelle and her sister Frieda attended clandestine schools and participated in a children’s theater.

From July to September 1942, German authorities rounded up more than 260,000 ghetto residents and transported them to the Treblinka killing center, where the vast majority were murdered upon arrival. This mass deportation is known as the Great Action (Grossaktion). During the Great Action, Estelle and her family hid in a secret room to escape being caught and sent on a transport. After the Great Action ended in September 1942, tens of thousands of Jews remained in the Warsaw ghetto. In this period, Estelle and her mother and sister had forced labor assignments in a factory mending German uniforms.

In April 1943, German forces made one last push to deport the remaining Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to forced labor camps or the Treblinka killing center. As SS and police units began roundups, Jewish resistance groups in the ghetto fought back. This act of armed Jewish resistance became known as the Warsaw ghetto uprising. For nearly a month, Jewish fighters resisted German SS and police units. Samek was part of the ghetto’s resistance movement and he had built a bunker in which he and his family hid during the uprising. The Germans burned down the ghetto block by block to draw out the people hiding in a network of underground bunkers.

As the Germans set fire to the ghetto, they threw grenades searching for underground bunkers. One of these grenades blew open the trapdoor to the family's bunker. The Germans dragged the Wakszlak family out onto the street, marched them to a central gathering point (called the Umschlagplatz), forced them to board freight train cars, and transported them to the Lublin-Majdanek concentration camp.

Upon arrival at Majdanek, the SS separated the women and men. Estelle, Michla, and Frieda were chosen for forced labor. Samek was ill with tuberculosis and weak from a beating he received at the hands of Germans in Warsaw. The women learned from another prisoner that he was murdered in the gas chamber. At Majdanek, Estelle and her mother and sister had to perform forced labor, including sorting through belongings stolen from murdered Jews. At one point Estelle witnessed a female German guard badly beat Frieda. Frieda could not work and she hid in the barracks, but was discovered.

One day, while Estelle and Michla were away, Frieda’s name was put on a list, supposedly for transfer to another camp. Estelle and Michla believed this was a trick and that the list was for prisoners who would be killed in the gas chambers. To stay together, even if it meant they would die, Estelle and Michla switched places with two women who were on the same list. Because their names were on this list, Michla, Estelle, and Frieda were sent to the Skarżysko forced labor camp to work in a HASAG (Hugo Schneider AG) munitions factory. They were later transferred to another HASAG factory at the Częstochowa forced labor camp.

Soviet forces liberated Estelle, Frieda, and Michla in Częstochowa in January 1945. To escape antisemitic violence in postwar Poland, the three women moved to Allied-occupied Germany and lived there until 1947, when they moved to the United States to join Michla’s two sisters and brother in New York City. Estelle was a volunteer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.