Rescue

Despite the indifference of most Europeans and the collaboration of others in the murder of Jews during the Holocaust, individuals in every European country and from all religious backgrounds risked their lives to help Jews. Rescue efforts ranged from the isolated actions of individuals to organized networks both small and large.

Rescue of Jews during the Holocaust presented a host of difficulties. The Allied prioritization of "winning the war" and the lack of access to those who needed rescue hampered major rescue operations. Individuals willing to help Jews in danger faced severe consequences if they were caught, and formidable logistics of supporting people in hiding. Finally, hostility towards Jews among non-Jewish populations, especially in eastern Europe, was a daunting obstacle to rescue.

Rescue took many forms.

Denmark

German-occupied Denmark was the site of the most famous and complete rescue operation in Axis-controlled Europe. In late summer 1943, German occupation authorities imposed martial law on Denmark in response to increasing acts of resistance and sabotage. German Security Police officials planned to deport the Danish Jews while martial law was in place. On September 28, 1943, a German businessman warned Danish authorities of the impending operation, scheduled for the night of October 1–2, 1943. With the help of their non-Jewish neighbors and friends, virtually all the Danish Jews went into hiding. During the following days, the Danish resistance organized a rescue operation, in which Danish fishermen clandestinely ferried some 7,200 Jews (of the country's total Jewish population of 7,800) in small fishing boats, to safety in neutral Sweden.

German-Occupied Poland

In the so-called Generalgouvernement (German-occupied Poland), some Poles provided assistance to Jews. For instance, Zegota (code name for Rada Pomocy Zydom, the Council for Aid to Jews), a Polish underground organization that provided for the social welfare needs of Jews, began operations in September 1942. Although members of the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa-AK) and the communist Polish People's Army (Armia Ludowa-AL) assisted Jewish fighters by attacking German positions during the Warsaw ghetto uprising in April 1943, the Polish underground provided few weapons and only a small amount of ammunition to Jewish fighters. From the beginning of the deportation of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka killing center in late July 1942 until the German occupiers leveled Warsaw in the autumn of 1944 after suppressing the Home Army uprising, as many as 20,000 Jews were living in hiding in Warsaw and its environs with the help of Polish civilians.

Religious Backgrounds

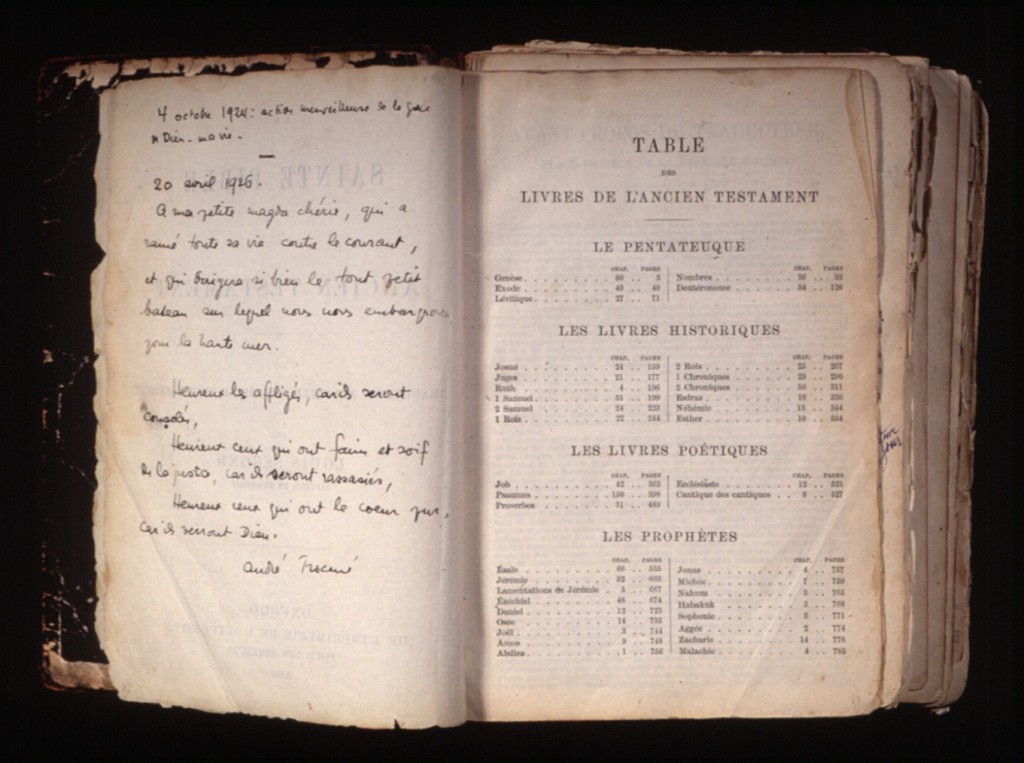

Rescuers came from every religious background: Protestant and Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Muslim. Some European churches, orphanages, and families provided hiding places for Jews, and in some cases, individuals aided Jews already in hiding (such as Anne Frank and her family in the Netherlands). In France, the Protestant population of the small village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon sheltered between 3,000 and 5,000 refugees, most of them Jews. In France, Belgium, and Italy, underground networks run by Catholic clergy and lay Catholics saved thousands of Jews. Such networks were especially active both in southern France, where Jews were hidden and smuggled to safety to Switzerland and Spain, and in northern Italy, where many Jews went into hiding after Germans occupied Italy in September 1943. And in Albania, where there was a majority Muslim population, over 2,000 Jews found refuge and protection from Nazi German authorities beginning in 1943.

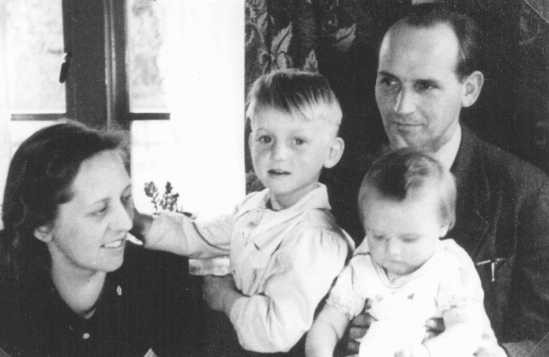

Individuals

A number of individuals also used their personal influence to rescue Jews. In Budapest, the capital of German-occupied Hungary, Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg (who was also an agent of the US War Refugee Board), Swiss diplomat Carl Lutz, and Italian citizen Giorgio Perlasca (posing as a Spanish diplomat), provided tens of thousands of Jews in 1944 with certification that they were under the "protection" of neutral powers. These certifications exempted the bearers from most anti-Jewish measures decreed by the Hungarian government, including deportation to the Greater German Reich. Each of these rescuers worked closely with members of the Budapest Jewish communities. For example, Perlasca, whose credentials were the most vulnerable to challenge, worked closely with Otto Komoly and the Szamosis—Laszlo and Eugenia—to obtain protective papers and shelter for scores of Jews in Budapest.

The Sudeten German industrialist Oskar Schindler took over an enamelware factory located outside the Krakow ghetto in German-occupied Poland. He later protected over a thousand Jewish workers employed there from deportation to Auschwitz.

The deportation of more than 11,000 Jews from Bulgarian-occupied Thrace, Macedonia, and Pirot to Treblinka in March 1943 by the Bulgarian military and police authorities shocked and shamed key political, intellectual, and religious figures in Bulgaria into an open protest against any deportations from Bulgaria proper. The protest action, which included members of the government's own ruling party, induced the Bulgarian King, Boris III, to reverse the decision of his government to comply with the German request to deport the Jews of Bulgaria. As a result of Boris' decision, the Bulgarian authorities did not deport any Jews from Bulgaria proper.

Other non-Jews sought to expose Nazi plans to murder the Jews. Among them was Jan Karski, a courier for the London-based Polish government-in-exile to the non-communist underground movements. Karski met with Jewish leaders in the Warsaw ghetto and in the Izbica transit ghetto in late summer of 1942. He transmitted their reports of mass killings in the Belzec killing center to Allied leaders, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with whom he met in July 1943.

Groups

Some US-based groups engaged in rescue efforts. The Quakers' American Friends Service Committee, the Unitarians, and other groups coordinated relief activities for Jewish refugees in France, Portugal, and Spain throughout the war. A variety of US-based organizations (both religious and secular, Jewish and non-Jewish) cooperated in securing entry visas into the United States and arranging placement and, in some cases, eventual repatriation for around 1,000 unaccompanied Jewish refugee children between 1934 and 1942.

Choices in Extreme Circumstances

Whether they saved a thousand people or a single life, those who rescued Jews during the Holocaust demonstrated the possibility of individual choice even in extreme circumstances. These and other acts of conscience and courage, however, saved only a tiny percentage of those targeted for destruction.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have influenced the decisions of rescuers?

Are these factors unique to this history or universal?

How can societies, communities, and individuals reinforce and strengthen the willingness to stand up for others?