Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

On April 19, 1943, the Warsaw ghetto uprising began after German troops and police entered the ghetto to deport its surviving inhabitants. Jewish insurgents inside the ghetto resisted these efforts. This was the largest uprising by Jews during World War II and the first significant urban revolt against German occupation in Europe. By May 16, 1943, the Germans had crushed the uprising and deported surviving ghetto residents to concentration camps and killing centers.

Key Facts

-

1

About 700 young Jewish fighters participated in what became known as the Warsaw ghetto uprising. During the uprising, the civilian population in the ghetto also resisted German forces by refusing to assemble at collection points and burrowing in underground bunkers.

-

2

At least 7,000 Jews died fighting or in hiding in the ghetto. Approximately 7,000 Jews were captured by the SS and police at the end of the fighting. These Jews were deported to the Treblinka killing center where they were murdered.

-

3

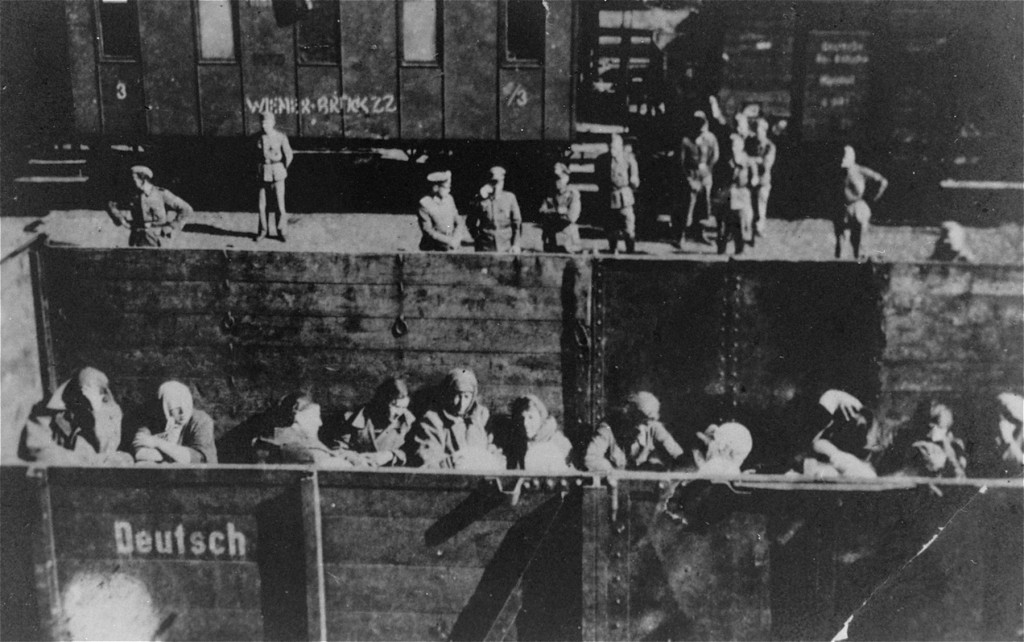

After the Warsaw ghetto uprising, the SS and police deported approximately 42,000 Jews to forced-labor camps and to the Lublin/Majdanek concentration camp. Most of these people were murdered in November 1943 in a two-day shooting operation known as Operation Harvest Festival (Erntefest).

Background

The Warsaw ghetto was the largest Jewish ghetto in German-occupied Europe. Established by the Germans in October 1940, and sealed that November, the ghetto housed approximately 400,000 Jews.

The “Great Action”

From July 22 until September 21, 1942, German SS and police units, assisted by auxiliaries, carried out mass deportations from the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka killing center. During what was described as the “Great Action,” the Germans deported about 265,000 Jews from Warsaw to Treblinka. They killed approximately 35,000 Jews inside the ghetto during this operation. By early 1943, the surviving Jews in the Warsaw ghetto numbered approximately 70,000 to 80,000 individuals.

The Jewish Underground (ŻOB and ŻZW) in the Warsaw ghetto

The “Great Action” had been disguised as a “resettlement operation.” However, by late summer 1942 it was clear to many ghetto inhabitants that deportations from the ghetto meant almost certain death.

In response to these deportations, several Jewish underground organizations banded together on July 28, 1942. They created an armed self-defense unit known as the Jewish Combat Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa; ŻOB). It is estimated that ŻOB had roughly 200 members at the time of its formation.

There was also a second force organized by the right-wing Revisionist Zionist movement, especially its youth group, Betar. This second force was called the Jewish Military Union (Żydowski Związek Wojskowy; ŻZW).

Although initially there was tension between the ŻOB and the ŻZW, both groups worked together to oppose German attempts to destroy the ghetto. At the time of the uprising, the ŻOB had about 500 fighters in its ranks and the ŻZW had about 250.

During the summer of 1942, efforts to establish contact with the Polish military underground movement, called the Home Army (Armia Krajowa; AK), did not succeed. But in October, the ŻOB managed to establish contact with the AK. They obtained a small number of weapons, mostly pistols and explosives, from AK contacts.

The First Attempt at Resistance against the Germans

In January 1943, German SS and police units returned to the Warsaw ghetto to resume mass deportations. They planned to send thousands of the ghetto’s remaining Jews to forced-labor camps in the Lublin District of the General Government.

A small group of Jewish fighters, armed with pistols, infiltrated a column of Jews being forced to the Umschlagplatz (transfer point). At a prearranged signal, this group broke ranks and fought their German escorts. Most of the Jewish fighters died in the battle. However, the attack disoriented the Germans. As a result, the Jews who were arranged in columns at the Umschlagplatz had a chance to disperse.

Jewish resistance leaders also encouraged fellow ghetto inhabitants to defy deportation orders and hide from German authorities. Seizing only 5,000-6,500 ghetto residents, the Germans suspended further deportations on January 21.

Encouraged by the apparent success of the resistance, people in the ghetto began to construct subterranean bunkers and shelters. They were preparing for an uprising should the Germans attempt a final deportation of the remaining Jews from the ghetto.

April 19, 1943-May 16, 1943

On April 19, 1943, the eve of the Passover holiday, the Jews of the Warsaw ghetto began their final act of armed resistance against the Germans. Lasting twenty-seven days, this act of resistance came to be known as the Warsaw ghetto uprising.

The Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) had received advanced warning of a final deportation action planned by the Germans. In response, the ŻOB warned residents of the ghetto to retreat to their hiding places or bunkers.

German Preparations

Based on their experience earlier that year in January, German authorities had knowledge of the ghetto’s defense organizations. On the eve of the action, they replaced the chief of the SS and Police in Warsaw, SS-Oberführer Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg, with SS and Police Leader [SS- und Polizeiführer] Jürgen Stroop. Stroop had considerable experience in partisan warfare. He also had considerable forces at his disposal. These forces included around 2,000 soldiers and police, reinforced with artillery and tanks.

Jewish Resistance

Twenty-four year old ŻOB commander Mordecai Anielewicz commanded the Jewish insurgents. The ŻOB fighters were armed with only pistols, grenades (many of which were homemade), and a few automatic weapons and rifles. Nonetheless, they stunned the Germans and their auxiliaries on the first day of fighting. They forced German troops to retreat outside the ghetto wall. Stroop reported losing 12 men during the first assault on the ghetto. These men were either killed or wounded.

About 700 young Jewish fighters clashed with German forces, sometimes in hand-to-hand combat. These fighters were poorly equipped and lacked military training and experience. The ŻOB did have the advantage of waging a guerilla war. They would strike, and then retreat, to the safety of ghetto buildings, bunkers, and underground tunnels. The general ghetto population likewise thwarted German deportation efforts, refusing to assemble at collection points and burrowing in underground bunkers.

In the end, the Germans razed the ghetto to the ground. They burned and demolished this part of Warsaw, block by block, in order to smoke out their prey.

The ghetto fighters and the civilian population who supported them held the Germans at bay for nearly a month. On May 8, 1943, German forces succeeded in seizing ŻOB headquarters at 18 Mila Street. Anielewicz and many of his staff commanders are thought to have committed suicide in order to avoid capture.

On May 16, Stroop announced in his daily report to Berlin that “The former Jewish Quarter in Warsaw is no more.”

The entire sky of Warsaw was red. Completely red.

—Benjamin Meed (oral history)

To symbolize the German victory, Stroop ordered the destruction of the Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street on May 16, 1943. The ghetto itself lay in ruins.

Casualties

The SS and police deported approximately 42,000 Warsaw ghetto survivors who were captured during the uprising. These people were sent to the forced-labor camps at Poniatowa and Trawniki, and to the Lublin/Majdanek concentration camp. Most of them would be murdered at these camps in November 1943 in a two-day shooting operation known as Operation Harvest Festival (Erntefest).

At least 7,000 Jews died fighting or in hiding in the ghetto. Approximately 7,000 Jews were captured by the SS and police at the end of the fighting. These Jews were deported to the Treblinka killing center where they were murdered.

For months after the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, individual Jews continued to hide in the ruins of the ghetto. On occasion, they attacked German police officials on patrol. After the ghetto was liquidated, perhaps as many as 20,000 Warsaw Jews continued to live in hiding on the so-called Aryan side of Warsaw.

Legacy and Remembrance

The Warsaw ghetto uprising was the largest and, symbolically, most important Jewish uprising during World War II. It was also the first urban uprising in German-occupied Europe. The Jewish resistance in Warsaw inspired uprisings in other ghettos such as in Bialystok.

Today, Days of Remembrance ceremonies to commemorate the victims and survivors of the Holocaust are linked to the dates of the Warsaw ghetto uprising.