Le Chambon-sur-Lignon

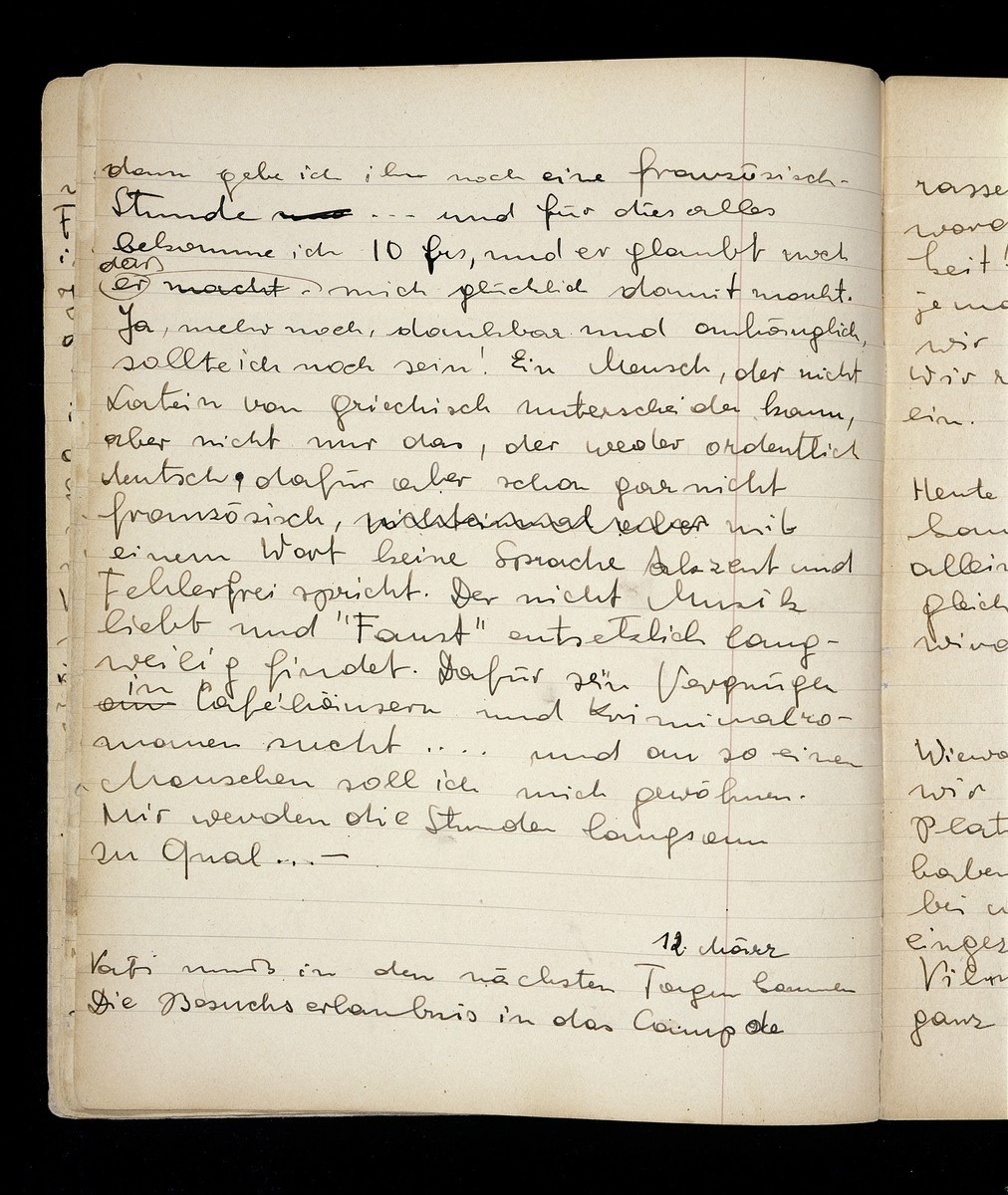

"Nobody asked who was Jewish and who was not. Nobody asked where you were from. Nobody asked who your father was or if you could pay. They just accepted each of us, taking us in with warmth, sheltering children, often without their parents—children who cried in the night from nightmares."

—Elizabeth Koenig-Kaufman, a former child refugee in Le Chambon

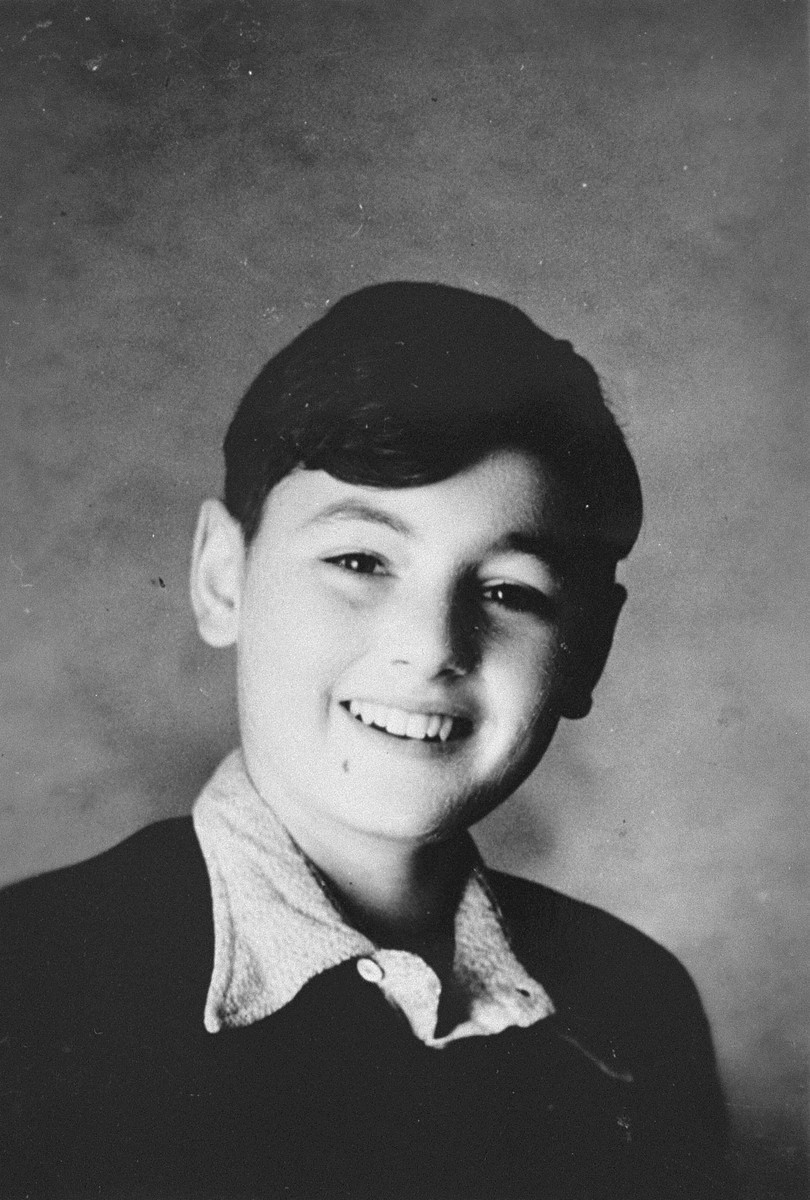

From December 1940 to September 1944, the inhabitants of the French village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (population 5,000) and the villages on the surrounding plateau (population 24,000) provided refuge for an estimated 5,000 people. This number included about 3,000–3,500 Jews who were fleeing from the Vichy authorities and the Germans.

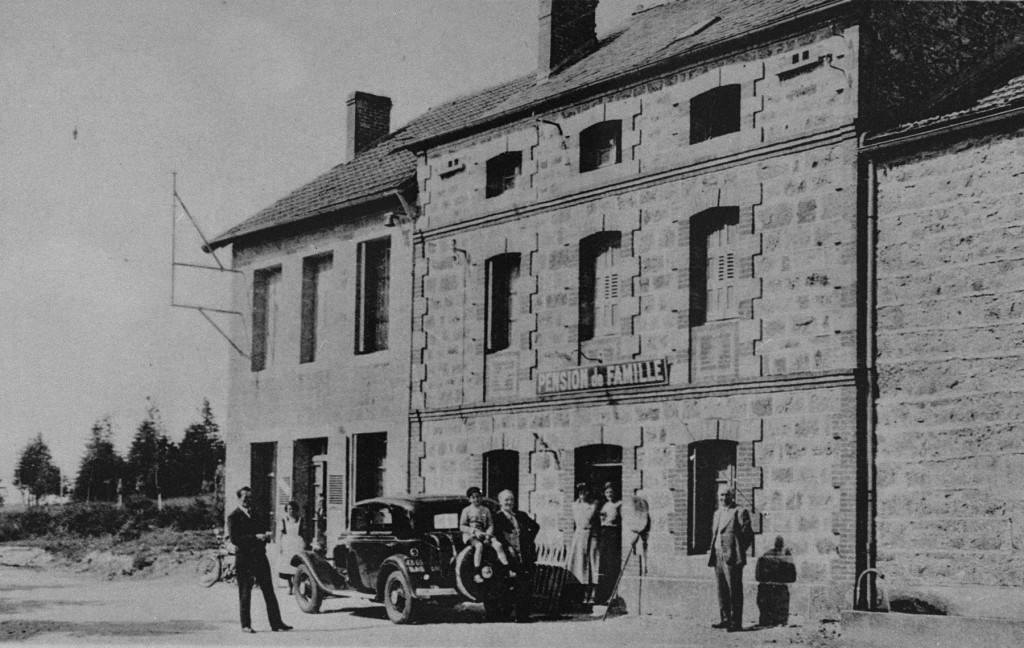

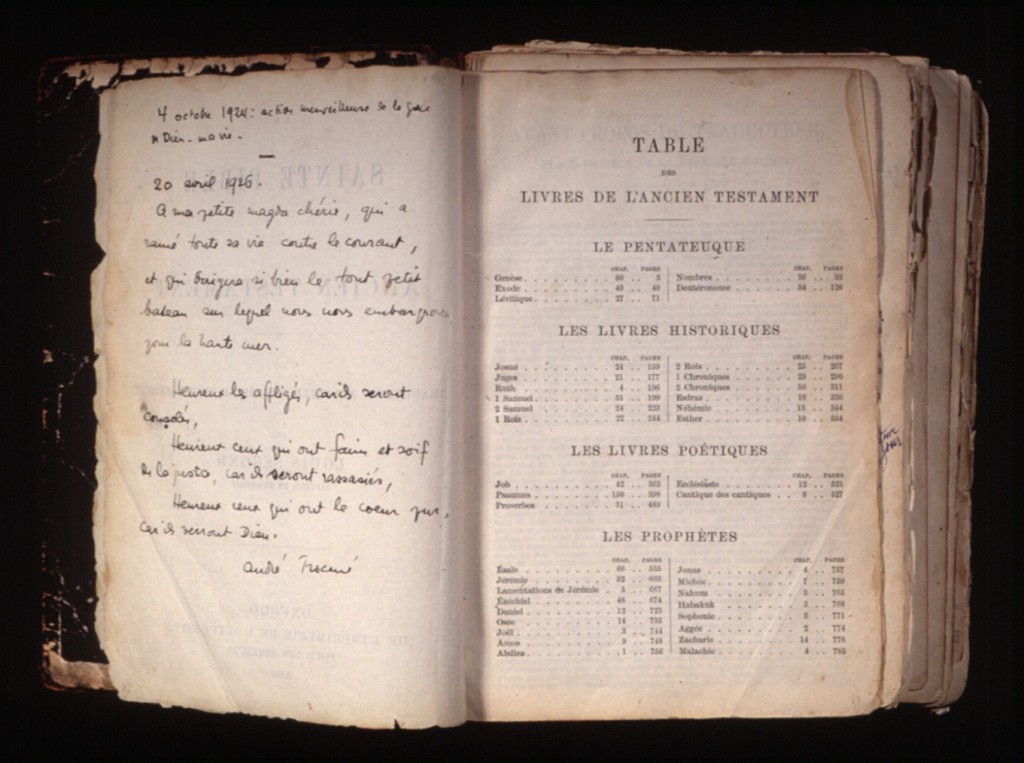

Led by Pastor André Trocmé of the Reformed Church of France, his wife Magda, and his assistant, Pastor Edouard Theis, the residents of these villages offered shelter in private homes, in hotels, on farms, and in schools. They forged identification and ration cards for the refugees, and in some cases guided them across the border to neutral Switzerland. These actions of rescue were unusual during the period of the Holocaust insofar as they involved the majority of the population of an entire region.

Background

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon is a village on the Vivarais Plateau in the Haute-Loire départment of the Auvergne, a hilly region of south-central France. Until November 1942, it lay in the Unoccupied Zone of France. The history of Le Chambon and its environs influenced the conduct of its residents during the Vichy regime and under German occupation. As Huguenot (Calvinist) Protestants, they had been persecuted in France by the Catholic authorities from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries and later provided shelter to fellow Protestants escaping discrimination and persecution. Many in Le Chambon regarded the Jews as a “chosen people” and, when they escorted those who were endangered 300 kilometers to the Swiss border, the guides were aware that they were following the same route that their persecuted Huguenot brethren had traveled centuries earlier.

On the Vivarais Plateau, the collective memory of their own suffering as a religious minority created a strong suspicion of authoritarian governments. Most Huguenots in the area refused to cooperate with the Vichy government, refused to take an oath to Marshal Pétain (chief of state of the Vichy regime), and refused to ring church bells in his honor. After the Vichy government was established in June 1940, André Trocmé, a committed pacifist, embarked on a campaign of peaceful civil disobedience against the authorities. Trocmé, who often preached against antisemitism, protested the mass roundup of Jews in Paris at the Vélodrome d'Hiver in July 1942 in a public sermon on August 16, stating that “the Christian Church must kneel down and ask God to forgive its present failings and cowardice.”

While the Trocmés and Theis were the principal catalysts of non-violent rescue activity on the Vivarais Plateau, the effort involved many others, including Protestant pastors in nearby parishes, as well as Catholics, American Quakers, Jews, Swiss Protestants, Evangelicals, students of various faiths, and non-believers.

Rescue

The organized rescue effort began during the winter of 1940, when Pastor Trocmé established contact with the American Friends Service Committee (Quakers) in Marseille in order to assist in providing relief supplies to the 30,000 foreign Jews held in internment camps in southern France. Trocmé initiated a working relationship with Burns Chalmers, a leading American Quaker, who told him that while the Quakers might be able to get internees released from the camps, there was no place for them to go, since no one was prepared to offer them shelter.

Trocmé assured Chalmers that his village, Le Chambon, would take in refugees. Chalmers was able to negotiate the release of many Jews, especially children, from some of the southern camps, including Gurs, Les Milles, and Rivesaltes. In addition to those who arrived in Le Chambon as a result of this organized rescue effort, Jews and others in danger also found their way to the town as individuals or in small groups, once word of mouth identified the Vivarais Plateau as a hospitable place of refuge.

The refugees were mostly foreign-born Jews, who did not hold French citizenship. A majority of them were children. They were dispersed among the small isolated villages and farms in the mountainous region surrounding Le Chambon. OSE (Oeuvre de Secours Aux Enfants, Children's Aid Society), a French-Jewish child care agency, played an important role in escorting children to Le Chambon and placing them in private homes, boarding houses, and in seven houses funded specifically to shelter them.

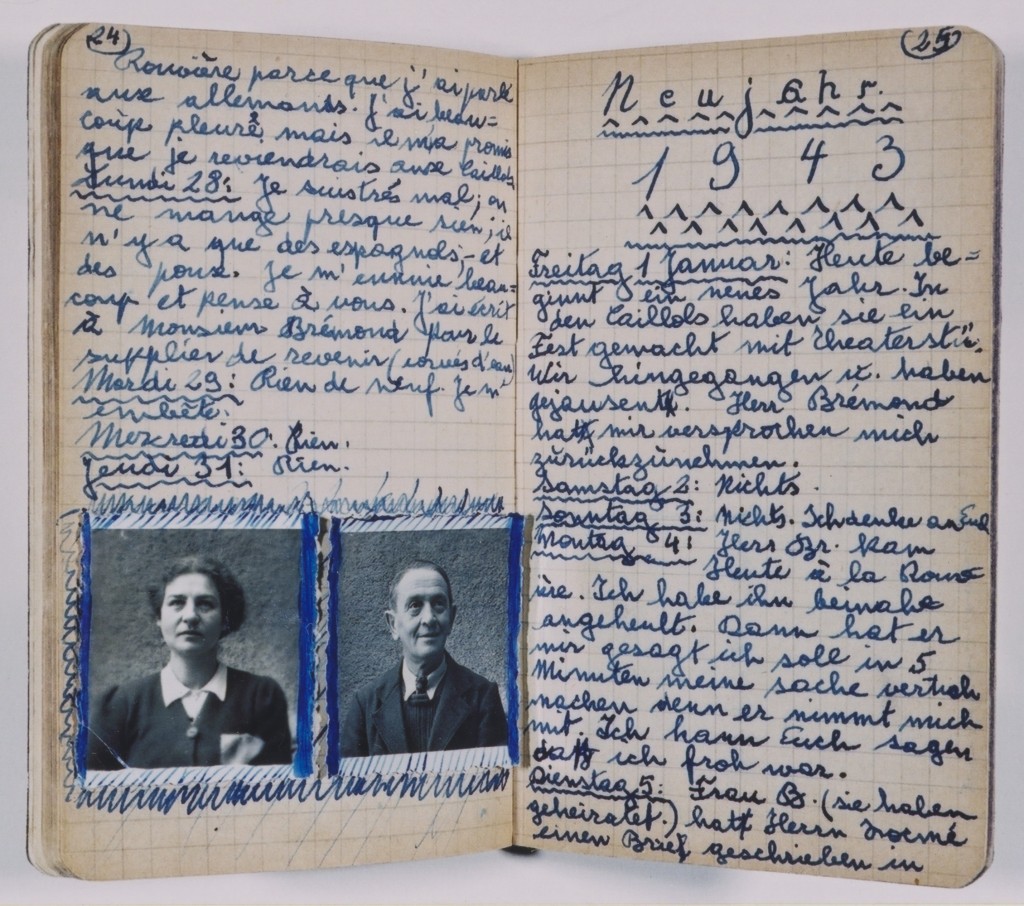

The Quaker organization, American Congregationalists, the Swiss Red Cross, and even national governments like Sweden contributed funding to maintain the houses. The refugees received food, clothing, and false identity documents. The sheltered children even attended school and took part in youth organizations. In order to maintain an appearance of normalcy and to conceal the presence of Jews in the communities, the children frequently attended Protestant religious services. Nevertheless, Trocmé also encouraged these Jews to hold clandestine Jewish services.

Whenever the villagers got wind of impending visits by the Vichy police or German Security Police raids, they moved the refugees further into the countryside, escorting some to the Swiss border. The CIMADE (Comite Inter-Mouvements Aupres Des Evacues, Committee to Coordinate Activities for the Displaced), a Protestant refugee organization, was especially active in finding escape routes to Switzerland. One common underground route led from Le Chambon to Annemasse and over the Swiss border.

Hunted by the Vichy authorities and the Germans, other refugees followed the Jews to Le Chambon, seeking sanctuary. Among them were Spanish Republicans who had fled internment camps, anti-Nazi Germans, and many young Frenchmen seeking to avoid deportation to Germany for forced labor. The region also sheltered members of the French resistance, which became active in the region in 1942.

Under German Occupation

The unity and solidarity of the local population compelled the Vichy authorities to proceed with caution in the region. Sometimes Vichy police officials gave the villages informal warnings before conducting searches. This pattern changed, however, after the Germans occupied southern France in November 1942. On February 13, 1943, French police arrested Pastors Trocmé and Theis, as well as the headmaster of the local primary school, Roger Darcissac, and interned them at a camp in Saint-Paul d'Eyjeaux, near Limoges. The French authorities released the three men after 28 days, and they continued to operate rescue activities until late 1943, when rumors of re-arrest sent them into hiding themselves. At that point, Magda Trocmé took over the leadership of the rescue enterprise.

On June 29, 1943, the German police raided a local secondary school and arrested 18 students. The Germans identified five of them as Jews, and sent them to Auschwitz, where they died. The German police also arrested their teacher, Daniel Trocmé, Pastor Trocmé's cousin, and deported him to the Lublin/Majdanek concentration camp, where the SS killed him. Roger Le Forestier, Le Chambon's physician, who was especially active in helping Jews obtain false documents, was arrested and subsequently shot on August 20, 1944, in Montluc prison on orders of the Gestapo in Lyon.

The Vivarais Plateau was liberated by the Free French First Armored Division on September 2-3, 1944.

Recognition

In 1990, the State of Israel recognized all of the inhabitants of Le Chambon and those of nearby villages collectively as “Righteous Among the Nations.” In addition, as of December 2007, the Israelis have awarded 40 individuals from Le Chambon and its environs the designation of “Righteous.” French President Jacques Chirac officially recognized the heroism of the village during a visit there on July 8, 2004. In January 2007, the French government honored the inhabitants of Le Chambon at a ceremony in the Pantheon in Paris.

The village of Le Chambon and its neighboring villages offer an exceptional example of a collective rescue effort during the Holocaust.

Critical Thinking Questions

- What pressures and motivations may have spurred the leaders and the townspeople of Le Chambon to participate? What risks did they face?

- How important is the role of an individual leader to inspire a community to act toward a goal? What dynamics within a community or group might influence the possibility of efforts for rescue?