How and why did ordinary people across Europe contribute to the persecution of their Jewish neighbors?

Many Europeans witnessed acts of persecution, including violence against Jews and, later, deportations. While few were aware of the full extent of the Nazi "Final Solution," this history poses difficult and fundamental questions about human behavior and the context within which individual decisions are made.

Understanding more about how and why the Holocaust was possible raises challenging questions about modern society and the ease with which people can become complicit in human rights violations.

See related articles for background information related to this discussion.

Ordinary people behaved in a variety of ways during the Holocaust. Motives ranged from pressures to conform and defer to authorities, to opportunism and greed, to hatred. In many places, the persecution of Jews occurred against a backdrop of centuries of antisemitism. In Germany, many individuals who were not zealous Nazis nonetheless participated in varying degrees in the persecution and murder of Jews and other victims. Following German occupation, countless people in other countries also cooperated in the persecution of Jews.

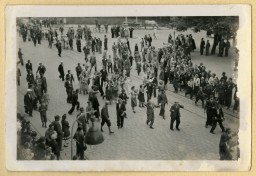

Everywhere, there were witnesses on the sidelines who cheered on the active participants in persecution and violence.

Most, however, remained silent.

Participation Inside Nazi Germany

Throughout the 1930s, many Germans assisted the Nazi regime’s efforts to remove Jews from Germany’s political, social, economic, and cultural life. Nazi activists—local Nazi leaders and members of Nazi paramilitary organizations, the SA and SS, and the Hitler Youth—used intimidation against Jews and non-Jews to enforce Nazi social and cultural norms. For example, they harassed Germans who entered Jewish stores or who showed friendliness toward Jews.

But even Germans who did not share the extreme Nazi belief that “the Jews” were a source of “racial pollution” participated in varying degrees in Jewish persecution. For instance, members of sports clubs, book groups, and other voluntary associations expelled Jews. Teenagers within schools and universities enjoyed their newfound freedom to harass Jewish classmates or even adults. Many ordinary Germans became involved when they acquired Jewish businesses, homes, or belongings sold at bargain prices or benefited from reduced business competition as Jews were driven from the economy. With such gains, these individuals developed a stake in the ongoing persecution.

Some landlords and neighbors denounced tenants or other individuals for private behavior they observed. This included the crime of “racial defilement,” sexual relations between Jews and persons of “German or related blood,” or violations of Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code, which prohibited homosexuality.

Germans who did not play an active role responded to Jewish persecution in diverse ways. Large numbers went along passively with the exclusion of Jews from their workplaces and with their isolation within schools and communities. Others cheered as onlookers to events such as public parades to shame those accused of “racial defilement.”

Nazi policies and actions, combined with the responses of elite and ordinary Germans, culminated in the near-total isolation of Jews from German society by late 1938. Although many Germans approved of the marginalization of Jews, they disapproved of the violence and destruction of property that occurred during the Nazi-led pogroms of November 9-10, 1938 (Kristallnacht). However, few spoke out. The same was true during the deportations of Jews from Germany after World War II began. In areas where the deportations did provoke some discontent, Nazi propagandists simply strengthened their efforts to promote acceptance of the removal of “the enemy within.”

Motives for Responses Inside Nazi Germany

Varying motivations influenced responses to the persecution of Jews and created a climate of passivity or apathy. Motivations ranged from belief in Nazi ideology to fear to self-interest. For instance, Nazi propaganda efforts heightened longstanding antisemitic prejudices and led many people to view the Jews as “alien.” The Nazis were also in near-total control of public space. Government censorship prevented dissenting voices from being heard, and few Germans had the courage to speak out publicly against the persecution of Jews. They were aware of the risk that outspoken dissidents faced in a police state, where opponents of the regime could be arbitrarily arrested and imprisoned in concentration camps without trial.

Pressures to defer to authority and obey laws and decrees were present even without the added intimidation by Nazi activists. Many people wanted to protect their jobs or advance their careers. Others did not want to “swim against the tide” by failing to conform to Nazi racist norms. Most cut off relations with Jewish friends and neighbors, in public if not in private.

The factor of fear and intimidation should not be overstated, however, for it implies that people wanted to help the persecuted. For many Germans, their livelihoods and the well-being of their families were simply a much higher priority than a group who represented a tiny fraction of the population and who was constantly demonized as a “dangerous threat.” As Germany’s economy and global standing improved during the 1930s, the majority of Germans—including many who never voted for Hitler and who did not identify as Nazi—supported the positive changes and overlooked the threats to Jews and other Nazi targets.

Participation in Areas of Eastern Europe under Direct Nazi Rule

Many more people came under direct Nazi rule once the war began. The manner in which ordinary people in these areas responded to the persecution of Jews varied depending on factors, such as country, region, degree of Nazi control, existing hostility toward Jews, and perceptions about whether Germany would win the war and remain the master of Europe.

After the invasion of Poland in 1939, western and southern Europe in 1940, and the Soviet Union in 1941, German forces became thinly stretched across vast occupied areas. They needed tens of thousands of non-Germans, from local officials and police to ordinary citizens, to help implement occupation policies, including measures that targeted Jews and other victims of Nazism.

In regions of eastern Europe under direct Nazi rule, non-Germans helped carry out Nazi policies including the ghettoization and forced labor of Jews, the seizure or transfer of Jewish property, and the roundup and transport of Jews to killing sites. During the Nazi-organized mass shootings of Jews, Communists, Roma, and psychiatric patients in Soviet territories, tens of thousands of non-German “auxiliary police” served as guards and killers. Local government officials recruited others to work as clerks, grave diggers, wagon drivers, and cooks. Some locals, at times on their own initiative, violently attacked Jews, robbing and killing them.

Motives for Non-German Responses in Eastern Europe

The motives of non-Germans who participated in the persecution and murder of Jews in Nazi-ruled eastern Europe varied. Nazi propaganda reinforced longstanding, local antisemitic prejudices. Ideologically-driven individuals were free to act within the climate of licensed violence against Jews. In places that the Soviets occupied between 1939 and 1941, local populations often blamed Jews as a group for oppressive Soviet policies. German propagandists aimed to deepen such animosity by constantly linking Jews and communists to a mythical “Judeo-Bolshevik” threat.

Tens of thousands of men joined auxiliary police forces or militias. Among their motivations for joining were the need for employment, income, and food, or the opportunity for gain, including self-enrichment from looted property. Some men aimed to prove loyalty to new German masters. Others sought the opportunity to avenge the suffering of their families under Soviet rule or to settle other scores. Radical nationalists in Ukraine and the Baltics (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) cooperated with the Germans because they hoped that the Germans would reward them by allowing them to establish independent, ethnically homogeneous states—hopes that were not realized.

Local policemen were drafted in to help guard the ghettos, sealed-off areas of towns where Jews were forced to live in appalling conditions. During the liquidation of the ghettos, these forces assisted the SS and other German police in the roundups and assembly of Jews for deportation to their deaths at Nazi killing centers. Not all regular police were eager collaborators, but they feared the consequences of disobeying German orders. In the countryside, some local police, along with volunteer firefighters, participated in “Jew hunts.”

Other locals informed on Jews in hiding. The opportunity for gain, either through payment by the Germans or the taking of Jewish belongings, tempted “Jew-hunters” in the countryside and cities. Blackmailers threatened to inform on Jews in hiding in order to extort money and belongings from them. Some locals hid Jews at first but then turned them in out of fear that they and their families would be shot if the Jews were discovered.

Participation, Motives, and Responses in Other Parts of Europe

In other parts of Europe that were allied with or occupied by Nazi Germany, some leaders and public officials helped, more or less zealously, to implement anti-Jewish policies. Measures included enacting discriminatory laws and decrees regarding citizenship, employment, and business ownership, and confiscating Jewish property. In some cases, such as in Romania, Hungary, Italy, Bulgaria, and France, non-German leaders—motivated by homegrown antisemitism, racism, and nationalism—acted on their own initiative. In all countries within the German sphere of domination, they helped identify, register, and mark Jews. Members of regular police and militarily trained gendarme forces rounded up Jews and assembled them for transport “to the East.” The Nazis disguised these deportations as “resettlement for labor.” Non-German railway workers transported deportees to the border.

The presence of “Jew-hunters,” some of them ideologically aligned with the Nazis, and many of them tempted by the lure of monetary rewards, reduced the possibility of Jews’ survival in hiding. This was the case even in a country like the Netherlands, where homegrown hostility toward Jews was not that prevalent before the war.

The War as Motivation

In general, the Germans’ ability to leverage their power to win cooperation from non-Germans was much greater before their defeat at Stalingrad (winter 1942–1943), a major turning point in the war. Many Europeans who had thought Germany would remain the master of Europe into the foreseeable future began to envision the possibility of German defeat. They became less eager to participate in actions that they might be held accountable for after the war. Changing perceptions about the outcome of the war also emboldened organized resistance efforts. By the fall of 1943, the likelihood of German defeat was strong. By this time, however, it was too late for most of Europe’s Jews. Five million were dead.

Individuals Who Aided Jews

A small minority of individuals, alone or in organized networks, took risks to help Jews. Aid came in several forms. Some offered gestures of solidarity. In Paris, for example, some non-Jews wore Star of David badges in protest. In some German cities, non-Jews sometimes greeted Jews wearing the star. Other individuals risked punishment and death by attempting to save Jews. They hid Jews during roundups, provided them food, alerted them to danger, and safeguarded their belongings.

Critical Thinking Questions

Investigate how professions and tasks in a society not related to the actual physical mistreatment of minorities can contribute to persecution and even murder.

Consider what attitudes, conditions, and beliefs in a society may make it easier to ignore persecution and murder? Investigate examples from this period.

Why do you think that after the war most people across Europe chose to believe that the Nazis alone were responsible for these crimes? What dangers do such myths pose today? What are the implications of not facing difficult aspects of one's own past?