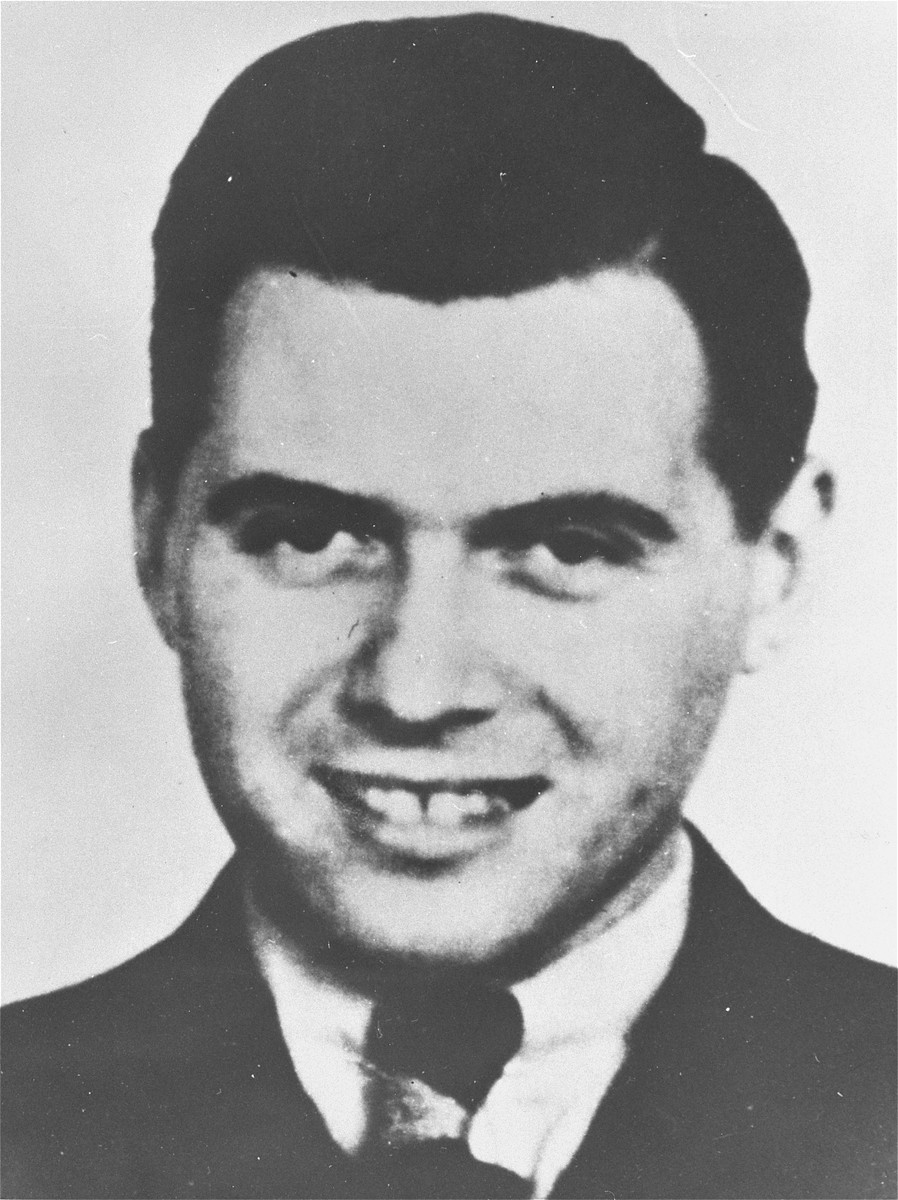

Josef Mengele

SS physician Josef Mengele conducted inhumane, and often deadly, medical experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz. He became the most notorious of the Nazi doctors who conducted experiments at the camp. Mengele was nicknamed the "angel of death." He is often remembered for his presence on the selection ramps at Auschwitz.

Key Facts

-

1

Mengele used Nazi racial theory to justify a wide spectrum of experiments on Jews and Roma ("Gypsies").

-

2

Many of the people subjected to experiments at Auschwitz died as a result of the procedures. In some experiments, death was the intended outcome.

-

3

Mengele escaped to South America after the war and evaded justice for his crimes. He died in Brazil in 1979.

Introduction

Josef Mengele is one of the most infamous figures of the Holocaust. His service at Auschwitz and the medical experiments he conducted there have made him the most widely recognized perpetrator of the crimes committed at that camp. His postwar life in hiding has come to represent the international failure to bring the perpetrators of Nazi crimes to justice.

Because of his infamy, Mengele has been the subject of numerous popular books, films, and television shows. Many of these portrayals distort the real facts of Mengele’s crimes and take him out of his historical context. Some portray him as a mad scientist who conducted sadistic experiments with no scientific basis.

The truth about Mengele is even more disturbing. He was a highly trained doctor and medical researcher, as well as a decorated war veteran. He was respected in his field and worked for one of the leading research institutions in Germany. Much of his medical research at Auschwitz supported the work of other German scientists. He was one of dozens of biomedical researchers who conducted experiments on prisoners in Nazi concentration camps. He was also one of a number of medical professionals who selected victims to be murdered in the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

Mengele acted within the norms of German science under the Nazi regime. His crimes represent the extreme danger posed by science when it is conducted in the service of an ideology that denies the rights, dignity, and humanity of certain groups of people.

Mengele before Auschwitz

Josef Mengele was born on March 16, 1911, in the Bavarian city of Günzburg, Germany. He was the eldest son of Karl Mengele, a prosperous manufacturer of farming equipment.

Mengele studied medicine and physical anthropology at several universities. In 1935, he earned a PhD in physical anthropology from the University of Munich. In 1936, Mengele passed the state medical exams.

In 1937, Mengele began working at the Institute for Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene in Frankfurt, Germany. There, he was an assistant to the director, Dr. Otmar von Verschuer. Verschuer was a leading geneticist known for his research on twins. Under Verschuer’s direction, Mengele completed an additional doctorate in 1938.

Embracing Nazi Ideology

Mengele did not actively support the far-right Nazi Party before it came to power. However, in 1931, he joined the Stahlhelm, the paramilitary of a different right-wing party called the German National People’s Party. Mengele became a member of the SA (a Nazi Party paramilitary) when it absorbed the Stahlhelm in 1933. He ceased actively participating in the SA in 1934.

During his university studies, Mengele embraced racial science, the false theory of biological racism. He believed that Germans were biologically different from and superior to members of all other races. This theory was a fundamental tenet of Nazi ideology. The Nazi German regime used racial science to justify the forced sterilization of persons with certain physical or mental diseases or physical deformities. The Nuremberg Race Laws, which outlawed marriage between Germans and Jewish, Black, or Romani peoples, were also based upon racial science.

In 1938, Mengele joined the Nazi Party and the SS. In his work as a scientist, he sought to support the Nazi goal of maintaining and increasing the supposed superiority of the German “race.” Mengele’s employer and mentor, Verschuer, also embraced biological racism. In addition to conducting research, Verschuer and his staff—including Mengele—provided expert opinions to Nazi authorities who had to determine whether persons qualified as German under the Nuremberg Laws. Mengele and his colleagues also evaluated Germans whose physical or mental condition might qualify them to be forcibly sterilized or barred from marriage under German law.

Serving on the Eastern Front

In June 1940, Mengele was drafted into the German army (Wehrmacht). A month later, he volunteered for the medical service of the Waffen-SS (the military branch of the SS). At first, he worked for the SS Race and Settlement Main Office (RuSHA) in German-occupied Poland. There, Mengele evaluated the criteria and methods used by the SS to determine whether persons claiming to be of German descent were racially and physically suitable to qualify as Germans.

Around the end of 1940, Mengele was assigned to the engineering battalion of the SS Division “Wiking” as a medical officer. For about 18 months beginning in June 1941, he saw extremely brutal fighting on the eastern front. In addition, in the first weeks of Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union, Mengele’s division slaughtered thousands of Jewish civilians. Mengele’s service on the eastern front earned him the Iron Cross, both 2nd and 1st Class, and promotion to SS captain (SS-Hauptsturmführer).

Mengele returned to Germany in January 1943. While awaiting his next Waffen-SS assignment, he began to work again for his mentor Verschuer. Verschuer had recently become the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Genetics, and Eugenics (KWI-A) in Berlin.

Assigned to Auschwitz

On May 30, 1943, the SS assigned Mengele to Auschwitz. There is some evidence that Mengele himself requested this assignment. He worked as one of the camp physicians at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Auschwitz-Birkenau was the largest of the Auschwitz camps and also served as a killing center for Jews deported from across Europe. In addition to other duties, Mengele had responsibility for Birkenau's Zigeunerlager (literally, “Gypsy camp”). Beginning in 1943, nearly 21,000 Romani men, women, and children (pejoratively referred to as Zigeuner or “Gypsies”) were sent to Auschwitz and imprisoned in the Zigeunerlager. When this family camp was liquidated on August 2, 1944, Mengele participated in selecting the 2,893 Romani prisoners who were to be murdered in the Birkenau gas chambers. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed chief physician for the part of the Auschwitz camp complex called Auschwitz-Birkenau or Auschwitz II. In November 1944, he was assigned to the Birkenau hospital for the SS.

The “Angel of Death”: Selecting Prisoners to be Murdered

As part of their camp duties, medical staff at Auschwitz performed so-called selections. The purpose of the selections was to identify persons who were unable to work. The SS considered such persons useless and therefore murdered them. When transports of Jews arrived at Birkenau, the camp medical personnel selected some of the able-bodied adults to perform forced labor in the concentration camp. Those not selected for labor, including children and older adults, were murdered in the gas chambers.

Camp physicians at Auschwitz and at other concentration camps also conducted periodic selections in the camp infirmaries and barracks. They conducted these selections in order to identify prisoners who were injured or had become too ill or weak to work. The SS used various methods to murder these prisoners, including lethal injections and gassing. Mengele routinely carried out such selections at Birkenau. This caused some prisoners to refer to him as the “angel of death.” Prisoner Gisella Perl, a Jewish gynecologist at Birkenau, later recalled how Mengele’s appearance in the women’s infirmary filled the prisoners with terror:

We feared these visits more than anything else, because [. . .] we never knew whether we would be permitted to live [. . . .] He was free to do whatever he pleased with us.

- Quoted according to Gisella Perl’s memoir I was a Doctor in Auschwitz (New York: International Universities Press, 1948), 120.

After World War II, Mengele became infamous for his work at Auschwitz thanks to the accounts of prisoner physicians who had worked under him and of prisoners who had survived his medical experiments.

Mengele was one of some 50 physicians who served at Auschwitz. He was neither the highest ranking doctor in the Auschwitz camp complex nor the commander of the other doctors there. Nevertheless, his name is by far the best known of all the doctors who served at Auschwitz. One reason for this was Mengele’s frequent presence on the ramps where selections took place. When Mengele did not himself perform selection duty, he often still appeared at the ramps, looking among the prisoners for twins for his experiments. He was also looking for physicians to staff the Birkenau infirmary. Consequently, many survivors who underwent selection upon arrival at Auschwitz assumed that Mengele was the doctor who had selected them. However, Mengele performed this task no more often than his colleagues.

Biomedical Researchers at Auschwitz

The SS authorized German biomedical researchers to conduct unethical and lethal human experiments in the concentration camps. Auschwitz provided prisoners for human experiments conducted at various other camps. It also served as the site of a variety of human experiments. This is because of the number of prisoners sent there. The SS sent 1.3 million men, women, and children from many different national and ethnic backgrounds to Auschwitz. Researchers looking for human subjects who met specific criteria could more easily find them at Auschwitz than at other camps.

Mengele was one of more than a dozen SS medical personnel who conducted experiments on people imprisoned at Auschwitz. These doctors included:

- Eduard Wirths, the head Auschwitz physician;

- Carl Clauberg, a noted specialist in the treatment of infertility;

- Horst Schumann, who gassed thousands of patients with disabilities during the Nazi Euthanasia Program;

- SS physician Helmut Vetter, who conducted drug trials for the Bayer subsidiary of IG Farben on prisoners at Dachau, Auschwitz, and Gusen concentration camps;

- Johann Paul Kremer, a professor of anatomy.

These doctors saw their appointment to Auschwitz as an exciting opportunity to advance their research.

Types of Experiments Conducted

The experiments in the concentration camps permanently maimed many victims or caused them to die. In some experiments, death was the intended outcome for the victims. The medical professionals who conducted experiments at Auschwitz did not seek the prisoners’ consent or inform them of their treatment or possible effects. The types of experiments conducted at Auschwitz included:

- Testing methods of mass sterilization;

- Inflicting wounds on prisoners or infecting them with diseases to study the effects and to test treatments;

- Conducting unnecessary surgeries and procedures on patients for research purposes or to train medical professionals;

- Murdering and dissecting prisoners for anthropological and medical research.

Mengele’s Experiments at Auschwitz

Separate from his regular duties at Auschwitz, Mengele conducted research and experiments on prisoners. His mentor Verschuer may even have arranged Mengele’s assignment to Auschwitz for the purpose of supporting the research of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Genetics, and Eugenics (KWI-A). Throughout his time at Auschwitz, Mengele sent his colleagues in Germany blood, body parts, organs, skeletons, and fetuses. These were all taken from Auschwitz prisoners. Mengele collaborated on his colleagues’ research projects by conducting studies and experiments using prisoners.

In addition to his work with the KWI-A, Mengele also conducted his own experiments on Auschwitz prisoners. He hoped to publish the results and thereby gain the credentials to qualify for a university professorship.

In the course of his service at Auschwitz, Mengele organized a research complex located in a number of barracks. He chose his staff from among the prisoners who were medical professionals. Mengele was able to obtain up-to-date instruments and equipment for his research and even set up a pathology lab.

Research Goals

Mengele’s own research and the research he conducted for the KWI-A generally focused on how genes develop into specific physical and mental traits. When conducted ethically, this is a legitimate and important field of genetic research. However, the work of Mengele, Verschuer, and their colleagues was warped by their belief in a pseudoscientific theory of race that was fundamental to Nazi ideology. This theory held that human races are genetically distinct from each other. It established a hierarchy of races and stressed that “inferior” races are genetically more likely to exhibit negative traits than supposedly “superior” races. The hereditary traits that were considered supposedly negative included more than physical and mental illnesses and deficiencies. They also included socially unacceptable or immoral behaviors, such as vagrancy, prostitution, and criminality. According to the false theory of race, intermarriage between races passed negative traits to the supposedly “superior” races and undermined these races.

Mengele sought to identify specific physical and biochemical markers that could definitively identify the members of specific races. Mengele and his colleagues believed that finding such markers was vitally important for preserving the supposed racial superiority of the German people. For Mengele and his colleagues, the importance of the research justified conducting harmful and lethal experiments on people—in this case Auschwitz prisoners—whom they considered to be racially inferior.

Who were Mengele’s Victims?

Mengele drew his victims mainly from two ethnic groups: Roma and Jews. These groups were of particular interest to biomedical researchers in Nazi Germany. Nazi ideology considered both Roma and Jews to be “subhuman” and to pose a threat to the German “race.” For this reason, Nazi scientists did not consider medical ethics to apply to members of these groups.

While Mengele served at Auschwitz-Birkenau, more than 20,000 Roma were imprisoned there and hundreds of thousands of Jews arrived there on transports. Nowhere else in the world could scientists have access to so many members of these groups concentrated in one place. And nowhere else did they have the power to experiment on human beings in whatever way they wanted. One colleague recalled Mengele commenting that it would be a crime not to take advantage of the opportunities for human experimentation at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Roma

In addition to choosing Roma as subjects for his medical experiments, Mengele conducted an anthropological study of the Romani men, women, and children in the Zigeunerlager. When there was an outbreak of noma, a gangrene of the mouth, among Romani children in the camp, he assigned prisoner physicians to study it. Noma is a bacterial infection that primarily afflicts extremely malnourished children. However, Mengele believed that the Romani children at Auschwitz suffered from noma because of heredity rather than because of the conditions at the camp. The prisoner physicians discovered how to cure noma, which was normally fatal. Nevertheless, all of the children who were cured were eventually murdered in the gas chambers.

Twins

In the 1930s, twins were a major focus of human genetic research. Before World War II, Verschuer and other biomedical researchers used twins to study the hereditary basis of diseases. These earlier researchers obtained the consent of the twins or their parents, but it was difficult for researchers to enlist many twins. At Auschwitz, Mengele collected hundreds of pairs of twins from among the Jews who arrived there on transports and from among the Roma imprisoned there. No researcher had ever been able to study and experiment on such a large number of twins.

Mengele ordered his staff to measure and record every aspect of the twins’ bodies. He drew large amounts of blood from the twins and sometimes performed other painful procedures on them.

[...] They also gave us injections all over our bodies. As a result of these injections, my sister fell ill. Her neck swelled up as a result of a severe infection. They sent her to the hospital and operated on her without anesthetic in primitive conditions. (…)

From the account of Lorenc Andreas Menasche (also Menashe Lorenzi or Lorenzy), camp number A 12090.

Mengele also murdered sets of twins at the same time in order to conduct autopsies of their corpses. After he studied the autopsies, Mengele sent some of their organs to the KWI-A.

Persons with Congenital Anomalies

When he conducted selections of arriving Jews on the unloading ramps at the camp, Mengele looked for people with physical abnormalities. These people included dwarfs, people with gigantism, or persons who had a clubfoot. Mengele studied these people and then had them murdered. He sent their bodies to Germany for study by researchers.

Mengele also sought out Roma and Jews with heterochromia, a condition in which a person’s eyes differ from each other in color. One of Mengele’s colleagues at the KWI-A was particularly interested in this condition. Mengele had persons with heterochromia murdered at Auschwitz and sent their eyes to this colleague.

Children

Most of the victims of Mengele’s medical experiments were children. The children Mengele selected for experiments lived in separate barracks from the other prisoners and received somewhat better food and treatment. Mengele was friendly toward the children. In 1985, Moshe Ofer, a survivor of Mengele’s experiments, described his and his brother Tibi’s encounters with Mengele:

[Mengele] visited us as a good uncle, bringing us chocolate. Before applying the scalpel or a syringe, he would say: 'Don’t be afraid, nothing is going to happen to you…' ...he injected chemical substances, performed surgery on Tibi’s spine. After the experiments he would bring us gifts...In the course of later experiments, he had pins inserted into our heads. The puncture scars are still visible. One day he took Tibi away. My brother was gone for several days. When he was brought back, his head was all dressed in bandages. He died in my arms.

Mengele used children for his own experiments and also to support the work of the KWI-A. He collaborated in a study of the development of eye color by putting a substance supplied by one of his colleagues in the eyes of children and newborns. The results ranged from irritation and swelling to blindness and even death.

A prisoner who was assigned to care for the Jewish twins selected for Mengele’s experiments later described how the children reacted emotionally and physically to their treatment:

Samples of blood were collected first from the fingers and then from the arteries, two or three times from the same victims in some cases. The children screamed and tried to cover themselves up to avoid being touched. The personnel resorted to force. (…) Drops were also put into their eyes….Some pairs of children received drops in both eyes, and others in only one. ….The results of these practices were painful for the victims. They suffered from severe swelling of the eyelids, a burning sensation….

Evading Justice

In January 1945, as the Soviet Red Army advanced through western Poland, Mengele fled Auschwitz with the rest of the camp’s SS personnel. He spent the next few months serving at the Gross-Rosen concentration camp and its subcamps. In the final days of the war, he donned a German army uniform and joined a military unit. After the war ended, the unit surrendered to US military forces.

Posing as a German army officer, Mengele became a US prisoner of war. The US Army released him in early August 1945, unaware that Mengele's name was already on a list of wanted war criminals.

From late 1945 until spring 1949, Mengele worked under a false name as a farmhand near Rosenheim, Bavaria. From here he was able to establish contact with his family. When US war crimes investigators learned of Mengele’s crimes at Auschwitz, they tried to find and arrest him. Based on lies told by Mengele’s family, however, the investigators concluded that Mengele was dead. The US effort to arrest him forced Mengele to recognize that he was not safe in Germany. With financial support from his family, Mengele immigrated to Argentina under yet another false name in July 1949.

By 1956, Mengele was well established in Argentina and felt so safe that he obtained Argentine citizenship as José Mengele. In 1959, however, he learned that West German prosecutors knew he was in Argentina and were seeking his arrest. Mengele immigrated to Paraguay and obtained citizenship there. In May 1960, Israeli intelligence agents abducted Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and took him to Israel to be tried. Correctly guessing that the Israelis were also looking for him, Mengele fled Paraguay. With support from his family in Germany, he spent the rest of his life under an assumed name near São Paulo, Brazil. On February 7, 1979, Mengele suffered a stroke and drowned while swimming at a vacation resort near Bertioga, Brazil. He was buried in a suburb of São Paulo under the assumed name “Wolfgang Gerhard.”

The Discovery and Identification of Mengele’s Body

In May 1985, the governments of Germany, Israel, and the United States agreed to cooperate in tracking down Mengele and bringing him to justice. German police raided the home of a Mengele family friend in Günzburg, Germany, and found evidence that Mengele had died and been buried near São Paulo. Brazilian police located Mengele's grave and exhumed his corpse in June 1985. American, Brazilian, and German forensic experts positively identified the remains as those of Josef Mengele. In 1992, DNA evidence confirmed this conclusion.

Mengele eluded arrest for 34 years and was never brought to justice.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

Gisella Perl, I was a Doctor in Auschwitz (New York: International Universities Press, 1948), 120.

-

Footnote reference2.

Menashe Lorenzy (Lorenzi), camp number A 12090, was imprisoned in Auschwitz at the age of 10. He and his sister were victims of Mengele’s medical experiments. See the Archives of the State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau, Statements Collection, vol. 125, pp. 146–147. Cited according to Voices of Memory: Medical Experiments (Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Oświęcim, 2016), p. 58 (e-book).

-

Footnote reference3.

Quoted according to Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, ed. Yisrael Gutman and Michael Berenbaum. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994, p. 324-325.

-

Footnote reference4.

Excerpt from Elżbieta Piekut-Warszawska, “Dzieci w obozie oświęcimskim (wspomnienia pielęgniarki),” [Children in the Auschwitz camp (recollections of a nurse)] in Przegląd Lekarski, vol. 1 (1967), pp. 204–205. Cited according to Voices of Memory: Medical Experiments (Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Oświęcim, 2016). 60.

Critical Thinking Questions

Investigate the role of medical professionals during the Nazi regime.

What pressures and motivations existed in medicine during the Nazi era that might have made Mengele's activities and choices possible?