John Demjanjuk: Prosecution of A Nazi Collaborator

Overview

Born in Ukraine, John (Iwan) Demjanjuk was the defendant in four different court proceedings relating to crimes that he committed while serving as a collaborator of the Nazi regime.

Investigations of Demjanjuk's Holocaust-era past began in 1975. Proceedings in the United States twice stripped him of his American citizenship and ordered him deported. The US extradited him to Israel, where his conviction as “Ivan the Terrible” at the Treblinka killing center was reversed on appeal. Germany later tried him for crimes at the Sobibor killing center. The German case set an important precedent and led to subsequent prosecutions in Germany that are continuing more than 70 years after the Holocaust.

Some facts of Demjanjuk's past are not in dispute. He was born in March 1920 in Dobovi Makharyntsi, a village in Vinnitsa Oblast of what was then Soviet Ukraine. Conscripted into the Soviet army, he was captured by German troops at the battle of Kerch in May 1942. Demjanjuk immigrated to the United States in 1952 and became a naturalized US citizen in 1958. He settled in Seven Hills, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, and worked for many years in a Ford auto plant.

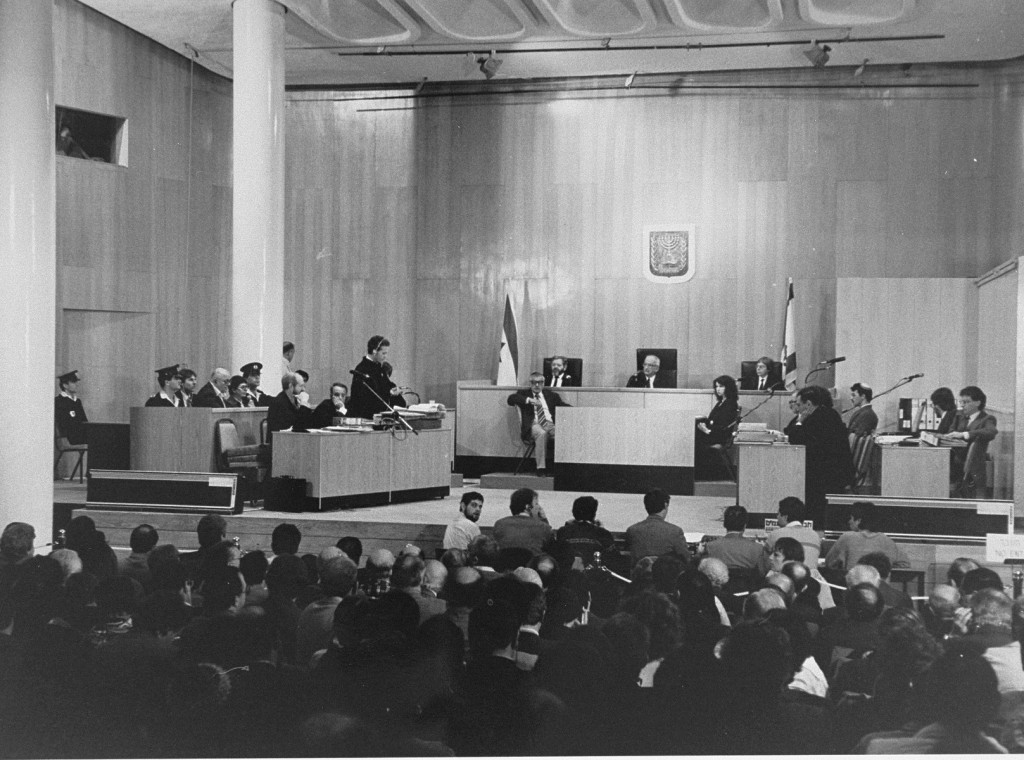

Demjanjuk's First Trial: Israel, 1987

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) began investigating John Demjanjuk in 1975 and filed denaturalization proceedings against him in 1977, alleging that he had falsified his immigration and citizenship papers in order to conceal World War II service at the Treblinka killing center.

The case had begun as an investigation into the Sobibor camp, due to Demjanjuk's alleged service at that killing center and to the testimony of a Soviet witness named Ignat' Danil'chenko in the late 1940s. Danil'chenko had stated that he knew Demjanjuk from their service together in Sobibor and at the Flossenbürg concentration camp until 1945. After Jewish survivors viewing a photo spread identified Demjanjuk as serving at Treblinka near the gas chambers, however, US government officials instead pursued the Treblinka charges. In 1979, the newly created Office of Special Investigations (OSI) in the DOJ took over prosecution of the case.

Following a lengthy investigation and a 1981 trial, the US District Federal Court in Cleveland stripped Demjanjuk of his US citizenship. As US authorities moved to deport Demjanjuk, the Israeli government requested his extradition. After a required hearing, US authorities extradited Demjanjuk to Israel to stand trial on charges of crimes against the Jewish people and crimes against humanity. Demjanjuk was only the second person to be tried for these charges in Israel. The first, Adolf Eichmann, was found guilty in 1961 and executed in 1962.

The trial opened in Jerusalem on February 16, 1987. The prosecution claimed that while Demjanjuk was a prisoner of war (POW) being held by the Germans, he volunteered to join a special SS (Schutzstaffel; Protection Squadrons) unit at the Trawniki training camp (near Lublin, Poland), where he trained as a police auxiliary to deploy in Operation Reinhard, the plan to murder all Jews residing in German-occupied Poland. The prosecution charged that he was the Treblinka killing center guard known to prisoners as “Ivan the Terrible,” and that he had operated and maintained the diesel engine used to pump carbon monoxide fumes into the Treblinka gas chambers. Several Jewish survivors of Treblinka identified Demjanjuk as “Ivan the Terrible,” key evidence placing him at the killing center.

Trawniki Training Camp

A critical piece of evidence was John Demjanjuk's Trawniki camp identification card, located in a Soviet archive. The authorities at Trawniki issued such documents to men detailed to guard detachments outside the camp. John Demjanjuk's defense claimed that the card was a Soviet-inspired forgery, despite several forensic tests that verified it as authentic. Demjanjuk, then 67 years old, testified on his own behalf, claiming that he had spent most of the war as a POW in German captivity in a camp near Chelm, Poland.

Though key to the American government's and the Israeli prosecution's case, the identity card did not place Demjanjuk in Treblinka, but rather as a guard at an SS estate in Okzów, near Chelm in September 1942, and as a guard at the Sobibor killing center from March 1943. Though the card contained some information that was inconsistent with the testimony of the Treblinka survivors, it was the only document available that placed Demjanjuk at Trawniki as a police auxiliary (that is, in the pool of auxiliaries from which Treblinka guards were selected). No wartime documentary evidence that definitively placed Demjanjuk at Treblinka has ever surfaced.

Demjanjuk's Tattoo

Another piece of evidence in the prosecution's case involved scars under John Demjanjuk's left arm, the remains of a tattoo identifying his blood type. SS authorities introduced the practice of blood-type tattooing into the Waffen-SS (Military SS) in 1942. Some members of SS Death's Head Units in the German concentration camp system also received such tattoos, as they were considered linked to the Waffen SS administratively after 1941. Nevertheless, blood-type tattooing was never consistently implemented. Hence this physical evidence only suggested, but by no means proved, that Demjanjuk might have served as a concentration camp guard.

The existence of scars from an “SS tattoo,” particularly given confusion in popular culture between the blood-type tattoo (mandatory) and the SS-rune tattoo (voluntary), misled prosecutors both in the United States and Israel as to its significance. There is no evidence that POWs trained as police auxiliaries at Trawniki received such tattoos.

Israeli Verdict and Appeal

Based primarily on the survivor identifications, the Israeli court convicted John Demjanjuk and, on April 25, 1988, sentenced him to death, only the second time that an Israeli court had imposed capital punishment upon a convicted defendant (the first being Eichmann).

As Demjanjuk's appeal made its way to the Israeli Supreme Court, the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991. Hundreds of thousands of pages of previously unknown documents became available to both the prosecution and the defense. In the records of the former Ukrainian KGB in Kiev, the Demjanjuk defense team found dozens of statements of former Treblinka guards whom Soviet authorities had tried in the early 1960s.

None of them identified Demjanjuk as having served at Treblinka. They did, however, consistently refer to an Ivan Marchenko, who had served as a gas motor operator at Treblinka from the summer of 1942 until the prisoner uprising in 1943, and who had stood out as a particularly cruel police auxiliary, perpetrating acts that were consistent with the memory of the Jewish Treblinka survivors. After returning to Trawniki in August 1943, Marchenko transferred to Trieste, Italy, and disappeared towards the end of the war. His fate remains unknown.

The existence of these statements alone, however, created sufficient reasonable doubt that Demjanjuk ever served at Treblinka, moving the Israeli Supreme Court to overturn Demjanjuk's conviction on July 29, 1993, without prejudice, signifying that the Israeli prosecution could choose to try Demjanjuk on charges related to other crimes.

New Evidence from Former Soviet Archives

Such a proceeding became possible upon the discovery of internal Trawniki training camp personnel correspondence in the Archives of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation in Moscow. These documents placed Demjanjuk at the Sobibor killing center as of March 26, 1943, and at the Flossenbürg concentration camp as of October 1, 1943. The evidence placing him at Sobibor was consistent with the information on Demjanjuk's Trawniki identification card and with Danil'chenko's testimony.

Moreover, after Demjanjuk's extradition to Israel, investigators at the OSI, while reviewing original personnel and administrative records from Flossenbürg, found references to Demjanjuk's name linked to his Trawniki military identification number (1393), thus independently corroborating Danil'chenko's testimony that Demjanjuk served at Flossenbürg.

In the summer of 1991, an OSI investigator searching in the Lithuanian National Archives in Vilnius for documentation related to a Lithuanian police battalion found by chance a document that placed Demjanjuk as a member of a Trawniki-trained guard detachment stationed at the Majdanek concentration camp between November 1942 and early March 1943.

American Citizenship Restored, Then Revoked Again

After his original extradition to Israel, Demjanjuk's family had filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the US Department of Justice to obtain access to all investigative files at the OSI that related to Demjanjuk, Trawniki, and Treblinka. Upon receiving these files, and after years of litigation, Demjanjuk's American defense team filed a suit against the US government to set aside the judgment stripping him of his citizenship, and accused the OSI of prosecutorial misconduct.

Meanwhile, despite having the legal option, Israeli authorities declined to prosecute Demjanjuk for his activities at Sobibor, and prepared to release him. Based on a June 1993 finding of a US Special Master that OSI had inadvertently withheld documentation that might have been helpful to the Demjanjuk defense in 1981, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati ordered the Attorney General of the United States, Janet Reno, not to bar Demjanjuk's return to the United States. After five more years of litigation, the District Court in Cleveland restored Demjanjuk's US citizenship on February 20, 1998, but without prejudice, leaving the option open for OSI to proceed with a new case based on new evidence.

With five years of careful review into thousands of Trawniki-related documents that had been unavailable before 1991, OSI investigators could track through wartime documents Demjanjuk's entire career as a Trawniki-trained guard and as a concentration camp guard from 1942 to 1945. With this new evidence, the OSI team had also developed a more thoroughly documented understanding of the importance of the Trawniki camp during the Holocaust as well as the process of how camp authorities made personnel assignments.

In 1999, OSI filed a new denaturalization proceeding against Demjanjuk, alleging that he served as a Trawniki-trained police auxiliary at Trawniki itself, Sobibor, and Majdanek, and, later, as a member of an SS Death's Head Battalion at Flossenbürg. As a result, in 2002 Demjanjuk again lost his American citizenship, this time for good. After a federal appeals court upheld this decision, OSI filed a deportation proceeding in December 2004. One year later, in December 2005, a US Immigration Court ordered Demjanjuk deported to his native Ukraine.

Demjanjuk appealed the deportation order on various grounds, including the argument that, given his age and poor health, deportation would constitute torture against which he was seeking protection under the United Nations Convention Against Torture. On May 19, 2008, the US Supreme Court declined to review his appeal. That same year, German authorities expressed interest in prosecuting Demjanjuk on charges of accessory to murder during his service at Sobibor.

Demjanjuk's Second Trial: Germany, 2009

John Demjanjuk was removed from the United States to Germany in May 2009. Upon his arrival, German authorities arrested him and held him in Munich's Stadelheim prison.

In July 2009, German prosecutors indicted Demjanjuk on 28,060 counts of accessory to murder at Sobibor. The German jurisdictional authority rested on the murder of people brought to Sobibor on 15 transport trains from the Westerbork camp in the Netherlands between April and July 1943, among whom were individual German citizens who had fled to Holland in the 1930s. For the first time in a German case, prosecutors argued that a guard at a facility whose sole purpose was mass murder shared responsibility for the deaths of those killed during his service there.

Demjanjuk, at 89 years old, claimed that he was too frail to stand trial, but the court ruled that the trial could proceed with two 90-minute sessions per day. In November 2009, he again sat in the defendant's dock. During this trial, the evidence implicating Demjanjuk rested not on survivor testimony, but on wartime documentation of his service at Sobibor. Since the earlier witnesses were now deceased, the Munich court accepted that survivor testimony be read into the proceeding to facilitate findings of mass murder and determine the identity and citizenship of many of the victims.

After 16 months of trial, proceedings closed in mid-March 2011. On May 12, 2011, Demjanjuk was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. He was freed pending appeal of the conviction.

The Death of John Demjanjuk

John Demjanjuk died in a German nursing home on March 17, 2012.

Although Demjanjuk died before a German appeals court could review his conviction, German prosecutors successfully prosecuted subsequent cases against killing center and concentration camp guards using the same theory tested in the Demjanjuk case.

International Interest

The trials of John Demjanjuk have attracted global media attention for three decades. These legal battles underscore the interdependence of the historical record and the long search for justice to redress crimes against humanity.

Critical Thinking Questions

Why were several countries involved in the prosecution of this case?

Why are Nazi war criminals still pursued and tried so many years after the Holocaust?

Why are some crimes tried in international courts, and not in the court of the country after a regime change?