Polish Jews in Lithuania: Escape to Japan

Background

The German attack on Poland in September 1939 trapped nearly 3.5 million Jews in German- and Soviet-occupied territories.

In late 1940 and early 1941, just months before the Germans initiated the mass murder of Jews in the Soviet Union, some 2,100 Polish Jews found temporary safe haven in Lithuania. Few of these refugees could have reached permanent safety without the tireless efforts of many individuals. Several Jewish organizations and Jewish communities along the way provided funds and other help.

But the most critical assistance came from unexpected sources: representatives of the Dutch government-in-exile and of Nazi Germany's Axis ally, Japan. Their humanitarian activity in 1940 was the pivotal act of rescue for Polish Jewish refugees temporarily residing in Lithuania.

Leaving Lithuania

The pressure on Polish Jewish refugees to leave Lithuania intensified in late 1940, when—after the Soviet takeover—the government ordered all refugees to declare Soviet citizenship or face exile to Siberia as "unreliable elements." Encouraged by the reports of those who traveled safely on the Trans-Siberian Railroad to the eastern port of Vladivostok, hundreds of Jewish refugees applied for Soviet exit visas. It remains unknown why the Soviets allowed refugees with Polish travel papers, many of dubious validity, to leave.

Not all refugees helped by the Dutch acting consul (Jan Zwartendijk) and Japanese acting consul (Chiune Sugihara) in Kovno left Lithuania for Japan. Some lacked the American dollars the Soviets demanded for the expensive railroad ticket. In the end, the Soviets granted permission to leave in an arbitrary manner. The Soviets even allowed refugees with only a Japanese visa to exit from Soviet territory. But most Lithuanian nationals did not apply for emigration. Under Communist rule they were Soviet citizens and accordingly were denied such freedom.

Trans-Siberian Train Journey

Between July 1940 and June 1941 about 2,200 Jewish refugees left Lithuania for Moscow, where they boarded the Trans-Siberian train. Most refugees stayed at the Hotel Novo Moskovskaia (New Moscow) during the brief stopover in Moscow. The Trans-Siberian train left Moscow twice a week. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee had the onerous task of choosing a limited number of refugees whom they could help by underwriting all or part of the $200 cost of an Intourist ticket for the train passage to Vladivostok.

Despite their many anxieties, most refugees felt like tourists on the train. When the train stopped at a settlement in the thinly populated Jewish autonomous region of Birobidzhan, close to the Manchurian border, many refugees spoke briefly with local Jews selling goods at the station.

Arrival in Japan

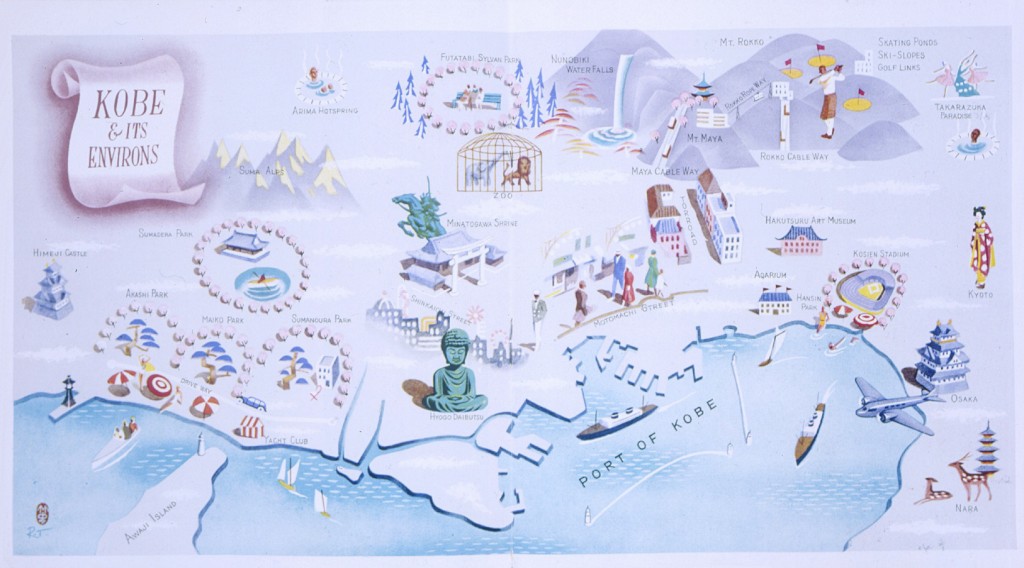

The Soviets confiscated currency and other valuables before the refugees boarded Japanese steamers in the port of Vladivostok. When the Jewish refugees reached Japan, most were destitute and lacked documents enabling them to proceed. With the consent of Japanese authorities, a representative of the Jewish community of Kobe met the refugees in Tsuruga and accompanied them on the train to Kobe. Using funds largely from the Joint Distribution Committee, the Jewish community—led by Anatole Ponevejsky—set up group homes, arranged for housing and food, and interceded on behalf of refugees in dealings with local officials.

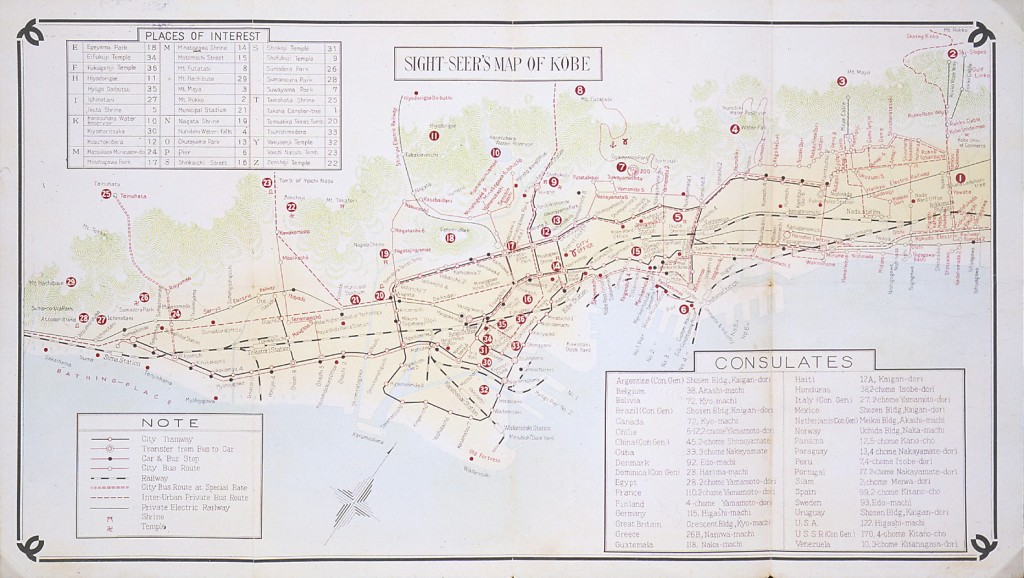

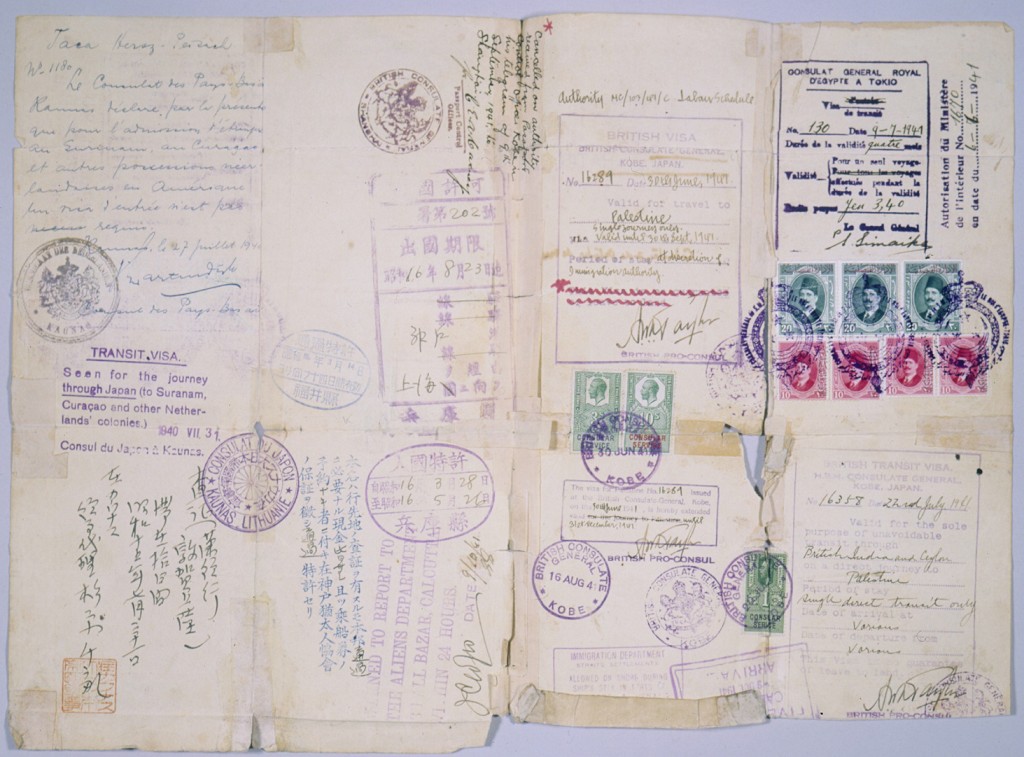

Bogus visas to the Dutch colony of Curacao in the Caribbean that had enabled the refugees to leave the Soviet Union proved useless for proceeding beyond Japan. Needing valid destination visas, the refugees made the round of consulates in Kobe, Yokohama, and Tokyo. More than 500 Polish Jews succeeded in obtaining US visas before December 1941, but new war-related immigration restrictions barred hundreds of others sponsored for entry. The State Department, for example, barred the issuing of visas to refugees with relatives in Axis-occupied territories. Certificates for entering Palestine were even scarcer and arrangements for traveling more complicated and expensive.

A minority of the refugees proceeded quickly to the United States and other countries. For hundreds of others the stay in Japan stretched from weeks into months. Many refugees despaired of ever obtaining final destination visas at the US and other consulates they visited. Most Polish Jewish refugees stayed in Japan much longer than their transit visas allowed. Many dreaded the day when authorities would no longer issue permits legally extending the period of residency.

The refugees remained concerned about family members in Poland from whom they had been separated. Postcards from home provided some comfort, but most communication by mail or telegram ceased after June 22, 1941, when German forces invaded the Soviet Union. Between June 22, 1941, and the defeat of Germany in 1945, the Germans killed more than three million Polish Jews. The refugees in Japan, however, knew little of this beyond vague rumors.

The Japanese public was hospitable toward the Jewish refugees in Japan. The Japanese were also intrigued; yeshiva (religious academy) students appeared particularly foreign. In Kobe, the refugees caught the interest of the avant-garde Tanpei Photography Club, whose members took photographs of many of the refugees in late April 1941. After the war, most refugees remembered the curiosity of the Japanese and noted the absence of antisemitic attitudes and behavior that they had endured in prewar Poland.

By the fall of 1941, more than 1,000 of the Polish Jewish refugees had left Japan. Nearly 500 sailed for the United States. Small groups gained permission to enter Canada and other British dominions. Close to 1,000 people remained stranded, having failed to secure any destination visas.

In July 1941, the United States imposed an embargo on oil exports to Japan. Soon thereafter, Japan occupied French Indo-China. The refugees' nervousness mounted at the sight of military exercises in Kobe, a major naval base, as war in the Pacific loomed. As Japan prepared for war in the weeks before its attack on Pearl Harbor, police cleared the military port of Kobe. From mid-August to late October 1941, they deported the rest of the refugees to Shanghai in Japanese-occupied China.