Children's Diaries during the Holocaust

Of the millions of children who suffered persecution at the hands of the Nazis and their Axis partners, a small number wrote diaries and journals that have survived. These young writers documented their experiences, confided their feelings, and reflected on the trauma they endured during these nightmare years.

Key Facts

-

1

Very few of the millions of children persecuted during the Holocaust wrote diaries and journals that have survived.

-

2

Each diary reflects a fragment of its author's life.

-

3

Taken together, the diaries provide readers with a varied and complex view of young people who lived and died during the Holocaust.

Introduction

When World War II ended in 1945, six million European Jews were dead, killed in the Holocaust. About 1.5 million of the victims were children.

Of the millions of children who suffered persecution at the hands of the Nazis and their Axis partners, only a small number wrote diaries and journals that have survived. In these accounts, the young writers documented their experiences, confided their feelings, and reflected on the trauma they endured during these nightmare years.

The Diary of Miriam Wattenberg

The diary of Miriam Wattenberg (“Mary Berg”) was one of the first children's journals which revealed to a wider public the horrors of the Holocaust.

Wattenberg was born in Lódz on October 10, 1924. She began a wartime diary in October 1939, shortly after Poland surrendered to German forces. The Wattenberg family fled to Warsaw, where in November 1940, Miriam, with her parents and younger sister, had to live in the Warsaw ghetto. The Wattenbergs held a privileged position within this confined community because Miriam's mother was a US citizen.

Shortly before the first large deportation of Warsaw Jews to Treblinka in the summer of 1942, German officials detained Miriam, her family, and other Jews bearing foreign passports in the infamous Pawiak Prison. German authorities eventually transferred the family to the Vittel internment camp in France, and allowed them to emigrate to the United States in 1944. Published under the penname “Mary Berg” in February 1945, Miriam Wattenberg's diary was one of the very few eyewitness accounts of the Warsaw ghetto available to readers in the English-speaking world before the end of World War II.

The Diary of Anne Frank

Anne Frank, who wrote her diary in hiding with her family and a handful of acquaintances in an attic warehouse in Amsterdam, is the most famous child diarist of the Holocaust era.

Born Annelies Frank in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, on June 12, 1929, she was the second daughter of businessman Otto Frank and his wife Edith. When the Nazis seized power in January 1933, the Franks fled to Amsterdam in order to evade the anti-Jewish measures of the new regime. Anne had received an autograph book for her twelfth birthday and began to use the volume as her diary, keeping a detailed account of events that took place in the “secret annex.” Acting on an anonymous tip, the German Security Police discovered the Franks' hiding place on August 4, 1944, and deported the inhabitants of the annex via Westerbork to Auschwitz.

In late October or early November 1944, Anne and her sister Margot arrived with a transport from Auschwitz to Bergen-Belsen, where both succumbed to typhus in February or March 1945. Following the war, Anne's father, Otto Frank, the sole survivor of the group, returned to Amsterdam in the summer of 1945, where former employee Miep Gies gave him Anne's diary and some further papers which she had found in the annex after the arrests. The diary first appeared in the Netherlands in 1947. Published in English in 1952 as The Diary of a Young Girl, the wartime journal of Anne Frank has become one of the world's most widely read books, transforming its author into a symbol of the hundreds of thousands of Jewish children murdered in the Holocaust.

Categories of Diaries and Journals

The prominence of Anne Frank's diary served for a time to eclipse other in situ works written by children during the Holocaust. Nevertheless, as interest in the Holocaust has increased, so has the publication of many more diaries, shedding light on the wartime lives of young people under Nazi oppression.

Young journal writers of this period came from all walks of life. Some child diarists came from poor or peasant families. Others were born to middle-class professionals. Some grew up in wealth and privilege. A handful came from deeply religious families, while others grew up in an assimilated and secular community. A majority of child diarists, however, identified with Jewish tradition and culture regardless of their degree of personal faith.

Child diaries and journals from the Holocaust era can be grouped into three broad categories:

- Those written by children who escaped German-controlled territory and became refugees or partisans;

- Those written by children living in hiding; and

- Those maintained by young people as ghetto residents, as persons living under other restrictions imposed by German authorities, or, more rarely, as concentration camp prisoners.

Refugee Diaries

Refugee diaries were often composed in the late 1930s or early 1940s by children of assimilated Jewish parents from Germany, Austria, or the Czech lands. Many of these diaries address the issue of displacement, as all of these child writers had sacrificed the familiarity of home in order to seek refuge among strangers in distant countries.

Some writers, like Jutta Salzberg (b. 1926 in Hamburg, Germany), Lilly Cohn (b. 1928 in Halberstadt, Germany), Susi Hilsenrath (b. 1929 in Bad Kreuznach, Germany), and Elisabeth Kaufmann (b. 1926 in Vienna, Austria; d. 2003), fled with siblings or parents. Others, such as Klaus Langer (b. 1924 in Gleiwitz, Upper Silesia), Peter Feigl (b. 1929 in Berlin), Werner Angress (b.1920 in Berlin, Germany; d. 2010), and Leja Jedwab (b. 1924 in Bialystok, Poland), arrived alone in a strange land.

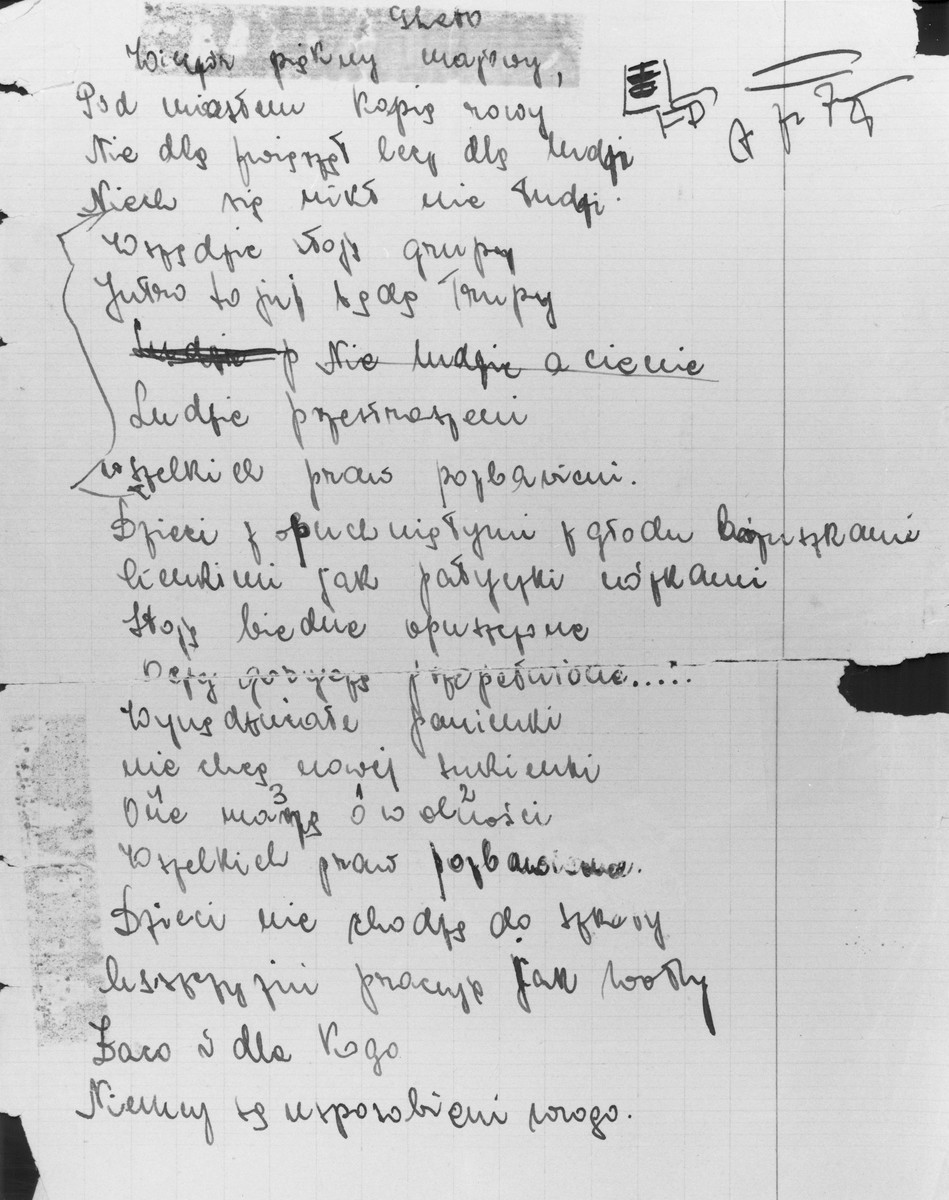

[caption=f421b0d4-482e-4142-9d5e-1f31c2100dc6] - [credit=f421b0d4-482e-4142-9d5e-1f31c2100dc6]

Child diarists who emigrated by legal means often described the tremendous bureaucratic difficulties involved in securing a safe haven and in obtaining the necessary visas and papers required for emigration. Diarists who fled illegally portray the harrowing journey through dangerous terrain and the constant fear of being apprehended.

Regardless of their means of escape, however, refugee diaries reflect the painful and confusing loss of home, language and culture; the devastating separation from family and friends; and the challenge of adapting to life in an unfamiliar and sometimes alienating world.

Diaries Written in Hiding

Like Anne Frank, some young people lived in hiding to evade the German authorities: in attics, bunkers, and cellars throughout eastern and western Europe. These writers—among them Otto Wolf (b. 1927 in Mohelnice, Czechoslovakia) in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; Mina Glucksman, Clara Kramer (b. 1927 in Zolkiew), and Leo Silberman (b. 1928 in Przemysl) in Poland; and Bertje Bloch-van Rhijn, Edith van Hessen (b. 1925 in The Hague), and Anita Meyer (b. 1929 in The Hague) in the Netherlands—reflect the difficulties and dangers of their concealment.

[caption=b8098dc0-b1bf-42b3-bd6e-4a240eb6fe27] - [credit=b8098dc0-b1bf-42b3-bd6e-4a240eb6fe27]

These children remained physically concealed for a significant portion, or for the entirety, of their time in hiding. Youngsters often had to remain silent or even motionless in their hiding places for hours at a time. Both children and their protectors lived in constant fear lest a raised voice or a footfall should rouse the suspicion of their neighbors.

Other young people in concealment, like child diarists Moshe Flinker (b. 1926, The Hague; d. 1944, Auschwitz) in Belgium and Peter Feigl in France, hid in plain sight, passing as non-Jews through the dubious protection of false papers and an assumed identity. These children had to adapt swiftly and completely to their new identities and environments. Young people learned to answer to their fictive name, and to avoid language or mannerisms that might betray their origins.

[caption=8823a760-a142-4421-9aeb-f33732a64591] - [credit=8823a760-a142-4421-9aeb-f33732a64591]

As most Jewish children were hidden by individuals or by religious institutions who embraced faiths different from their own, youngsters learned to recite the prayers and catechism of their “adopted” religion in order to avert the suspicions of both adults and their peers. One false word or gesture was sufficient to endanger both the child and his or her rescuers.

Diaries written in ghettos, camps, or occupied areas

Children and young people residing in ghettos in German-occupied Europe wrote the majority of diaries that have surfaced from the era of the Holocaust. Ghetto diaries often reflect the segregation, isolation, and vulnerability of their authors. They capture the extreme physical suffering and deprivation experienced by their authors and present the complex hardships and adversities that Jews faced in their struggle to survive. In ghetto diaries, the reader finds a firsthand account of the terror and violence of Nazi persecution, but also reads about young people who attempted to transcend their circumstances through study, creativity, and play.

The former sites of many ghettos in German-controlled eastern Europe, particularly in Poland and the former Soviet Union, have yielded many diaries and journals written by children. Renowned among them are the diaries of Dawid Sierakowiak (b. 1924 in Lódz; d. 1943, Lódz ghetto) and two anonymous teenagers from Lódz. Few complete diaries have been found from the Warsaw ghetto, but the fragmentary notes of Janina Lewinson (b. 1926, Warsaw; d. 2010) survived and were later incorporated in her latter-day memoir. Irena Gluck (b.1926- d. c. 1942), Renia Knoll (b. 1927), and Halina Nelken (b. 1924 in Kraków) wrote diaries in the Kraków ghetto, while Dawid Rubinowicz (b. 1927 in Kielce; d. 1942 at Treblinka), Elsa Binder, and Ruthka Leiblich (b.1926; d. c. 1942 in Auschwitz) wrote diaries recording persecution in their communities.

A number of wartime diaries came from ghettos in the Baltic countries: Yitskhok Rudashevski (b. 1927 in Vilnius; d. 1943, Ponary Woods) and Gabik Heller from the Vilne ghetto in Vilnius, Lithuania; Ilya Gerber (b. 1924; d. c. 1943) and Tamara Lazerson (b.1929 in Kaunas) from the Kovno (Kovne) ghetto, in Kaunas, Lithuania; and Gertrude Schneider (b. 1923 in Vienna), a German-Jewish girl incarcerated in the Riga ghetto.

Quite a large number of diaries survived from Theresienstadt in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), among them the writings of siblings Petr Ginz (b. 1928 in Prague; d. c. 1944, Auschwitz) and Eva Ginzová (b.1930 in Prague), Alice Ehrmann (b. 1927 in Prague), Helga Weissovà (b. 1929 in Prague), Helga Pollackovà (b. 1930), Eva Roubickovà (b. 1920), and Paul Weiner (b. 1931 in Prague).

Many diaries were written by children outside the walls of the ghetto. Sarah Fishkin (b. c. 1924; d. c. 1942) for example, kept a diary in occupied Belorussia (today, Belarus) in the town of Rubezhevichi. Riva Goltsman described the first unsettling six months of occupation in Dnepropetrovsk, in Ukraine. Leon Wells (b. 1925 in Stojanov by Lwów-today: L'viv) kept a diary as a young member of a Sonderkommando unit in the Janów Street forced-labor camp in Lvov (Lwów), while Günther Marcuse (b. 1923 in Berlin; d. 1944, Auschwitz) recounted his experiences in a forced-labor camp at Gross-Breesen, once a vocational training farm for Jewish youngsters hoping to emigrate from the Reich. Isabelle Jesion wrote her diary under German occupation in Paris, while Raymonde Nowodworski (b. 1929 in Warsaw; 1951 in Israel) portrayed her life in Centre Vauquelin, a children's home run by the L'Union générale des israélites de France (UGIF).

Each diary reflects a fragment

Diaries by children, teenagers, and young adults during the era of the Holocaust reflect a great variety of personal backgrounds and wartime circumstances. Their authors often addressed themes such as the nature of human suffering, the moral and ethical dimensions of persecution, and the struggle of hope against despair. Each diary reflects a fragment of its author's life, but, taken together, the diaries provide readers with a varied and complex view of young people who lived and died during the Holocaust.

Critical Thinking Questions

Why are diaries an important part of the historical record?

What makes children’s diaries distinct? What can we learn from them?

How are some of these accounts different from that of Anne Frank?