Warsaw

In the fall of 1940, German authorities established a ghetto in Warsaw, Poland’s largest city with the largest Jewish population. Almost 30 percent of Warsaw’s population was packed into 2.4 percent of the city's area.

Key Facts

-

1

Extreme overcrowding, minimal rations, and unsanitary conditions led to disease, starvation, and the death of thousands of Jews each month.

-

2

Various types of resistance took place in the Warsaw ghetto, ranging from documenting Nazi crimes against the Jews to armed resistance, culminating in the Warsaw ghetto uprising.

-

3

From July 22 until September 21, 1942, German SS and police units, assisted by auxiliaries, carried out mass deportations from the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka killing center.

The city of Warsaw, capital of Poland, flanks both banks of the Vistula River. A city of 1.3 million inhabitants, Warsaw was the capital of the resurrected Polish state in 1918. Before World War II, the city was a major center of Jewish life and culture in Poland. Warsaw's prewar Jewish population of more than 350,000 constituted about 30 percent of the city's total population. The Warsaw Jewish community was the largest in both Poland and Europe, and was the second largest in the world, second only to New York City.

Following the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, Warsaw suffered heavy air attacks and artillery bombardment. German troops seized Warsaw on September 27, 1939.

Less than a week later, German officials ordered the establishment of a Jewish council (Judenrat) under the leadership of a Jewish engineer named Adam Czerniaków. As chairman of the Jewish council, Czerniaków had to administer the soon-to-be established ghetto and implement German orders. On November 23, 1939, a decree issued by Hans Frank, Governor General of German-occupied Poland, required all Jews in his jurisdiction to identify themselves by wearing white armbands with a blue Star of David. This order also applied to the Jews of Warsaw. In the city, the German authorities closed Jewish schools, confiscated Jewish-owned property, and conscripted Jewish men into forced labor and dissolved prewar Jewish organizations.

Warsaw Ghetto

In October 1940, German officials decreed the establishment of a ghetto in Warsaw. The decree required all Jewish residents of Warsaw to move into a designated area, which German authorities sealed off from the rest of the city in November 1940. The ghetto was enclosed by a wall that was over 10 feet high, topped with barbed wire, and closely guarded to prevent movement between the ghetto and the rest of Warsaw. The population of the ghetto, increased by Jews compelled to move in from nearby towns, was estimated to be over 400,000 Jews. German authorities forced ghetto residents to live in an area of 1.3 square miles, with an average of 7.2 persons per room.

Conditions in the Ghetto

The Jewish council offices were located on Grzybowska Street in the southern part of the ghetto. Jewish organizations inside the ghetto tried to meet the needs of the ghetto residents as they struggled to survive. Among the welfare organizations active in the ghetto were the Jewish Mutual Aid Society, the Federation of Associations in Poland for the Care of Orphans, and the Organization for Rehabilitation through Training. Financed until late 1941 primarily by the New York-based American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, these organizations attempted to keep alive a population that suffered severely from starvation, exposure, and infectious disease.

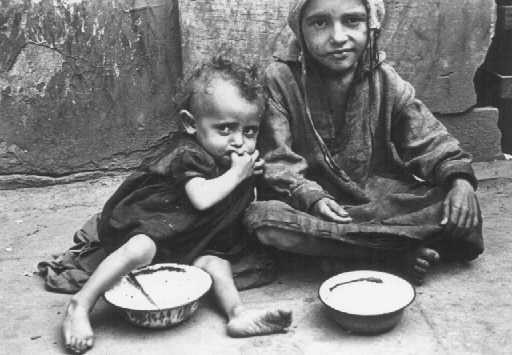

The hunger in the ghetto was so great, was so bad, that people were laying on the streets and dying, little children went around begging...

—Abraham Lewent

Food allotments rationed to the ghetto by the German civilian authorities were not sufficient to sustain life. In 1941 the average Jew in the ghetto subsisted on 1,125 calories a day. Czerniaków wrote in his diary entry for May 8, 1941: “Children starving to death.” Between 1940 and mid-1942, 83,000 Jews died of starvation and disease. Widespread smuggling of food and medicines into the ghetto supplemented the miserable official allotments and kept the death rate from increasing still further.

Documenting Life in the Ghetto

Emanuel Ringelblum, a Warsaw-based historian prominent in Jewish self-aid efforts, founded a clandestine organization that aimed to provide an accurate record of events taking place in German-occupied Poland while the ghetto existed. This record came to be known as the "Oneg Shabbat" ("In Celebration of Sabbath," also known as the Ringelblum Archive). Only partly recovered after the war, the Ringelblum Archive remains an invaluable source about life in the ghetto and German policy toward the Jews of Poland.

Deportations and Uprising

From July 22 until September 12, 1942, German SS and police units, assisted by auxiliaries, carried out mass deportations from the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka killing center, 84 kilometers (52 miles) away from Warsaw. During this period, the Germans deported about 265,000 Jews from Warsaw to Treblinka; they killed approximately 35,000 Jews inside the ghetto during the operation. Rather than fill the daily quotas for deportation, Jewish council leader Czerniaków committed suicide on July 23.

In January 1943, SS and police units returned to Warsaw, this time with the intent of deporting thousands of the remaining approximately 60,000 Jews in the ghetto to forced-labor camps for Jews in Lublin District of the Government General. This time, however, many of the Jews, understandably believing that the SS and police would deport them to the Treblinka killing center, resisted deportation, some of them using small arms smuggled into the ghetto. After seizing approximately 5,000 Jews, the SS and police units halted the operation and withdrew.

On April 19, 1943, a new SS and police force appeared outside the ghetto walls, intending to liquidate the ghetto and deport the remaining inhabitants to the forced labor camps in Lublin district. Spurred on by the ghetto resistance unit known as the Jewish Combat Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa; ŻOB), ghetto inhabitants offered organized resistance in the first days of the operation, inflicting casualties on the well-armed and equipped SS and police units. They continued to resist deportation as individuals or in small groups for four weeks before the Germans ended the operation on May 16. The SS and police deported approximately 42,000 Warsaw ghetto survivors captured during the uprising to the forced-labor camps at Poniatowa and Trawniki and to the Lublin/Majdanek concentration camp. At least 7,000 Jews died fighting or in hiding in the ghetto, while the SS and police sent another 7,000 to the Treblinka killing center.

For months after the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, individual Jews continued to hide themselves in the ruins and, on occasion, attacked German police officials on patrol. Perhaps as many as 20,000 Warsaw Jews continued to live in hiding on the so-called Aryan side of Warsaw after the liquidation of the ghetto.

The End of the War in Warsaw

On August 1, 1944, the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa; AK), the underground resistance force aligned with the Polish government-in-exile, rose against the German occupation authorities in an effort to liberate Warsaw. Though Soviet forces were in the vicinity of the city, they refused to intervene in support of the uprising. The city's civilian population fought alongside the Home Army against the well-armed German military. The Germans eventually crushed the revolt and razed the center of the city to the ground in October 1944. The Germans treated the civilians of Warsaw with extreme cruelty, deporting them to concentration and forced-labor camps. Tens of thousands civilians died in the Warsaw Uprising, including an unknown number of Jews who were hiding in the city or fighting as part of the uprising.

Soviet troops resumed their offensive in January 1945. On January 17, they entered a devastated Warsaw.

Critical Thinking Questions

Why did the Nazis resort to a system of ghettos?

How do the actions of the inhabitants of the Warsaw ghetto illustrate the many ways oppressed peoples may resist the perpetrators?

What factors and conditions might delay resistance by a persecuted group?

Investigate how the Jews of Warsaw tried to maintain their religious and cultural identity and their humanity under the extreme stress of SS rule and deportations.

Learn about the lives of the Jews in the community of Warsaw before 1939.