World War I: Aftermath

The Undermining of Democracy in Germany

In the years following World War I, there was spiraling hyperinflation of the German currency (Reichsmark) by 1923. The causes included the burdensome reparations imposed after World War I, coupled with a general inflationary period in Europe in the 1920s (another direct result of a materially catastrophic war). This hyperinflationary period combined with the effects of the Great Depression (beginning in 1929) to seriously undermine the stability of the German economy, wiping out the personal savings of the middle class and spurring massive unemployment.

Economic chaos increased social unrest and destabilized the fragile Weimar Republic. "Weimar Republic" is the name given to the German government between the end of the Imperial period (1918) and the beginning of Nazi Germany (1933).

View Aftermath of World War I and the Rise of Nazism, 1918–1933.

Efforts of the western European powers to marginalize Germany undermined and isolated its democratic leaders. Many Germans felt that Germany's prestige should be regained through remilitarization and expansion.

The social and economic upheaval that followed World War I gave rise to many radical right wing parties in Weimar Germany. The harsh provisions of the Treaty of Versailles led many in the general population to believe that Germany had been "stabbed in the back" by the "November criminals." By "November Criminals" they meant those who had helped to form the new Weimar government and broker the peace which Germans had so desperately wanted, but which had ended so disastrously in the Versailles Treaty.

Many Germans forgot that they had applauded the fall of the emperor (the Kaiser), had initially welcomed parliamentary democratic reform, and had rejoiced at the armistice. They recalled only that the German Left—Socialists, Communists, and Jews, in common imagination—had surrendered German honor to a disgraceful peace when no foreign armies had even set foot on German soil. This Dolchstosslegende (stab-in-the-back legend) was initiated and fanned by retired German wartime military leaders, who, well aware in 1918 that Germany could no longer wage war, had advised the Kaiser to sue for peace. It helped to further discredit German socialist and liberal circles who felt most committed to maintain Germany's fragile democratic experiment.

Vernunftsrepublikaner ("republicans by reason"), individuals like the historian Friedrich Meinecke and Nobel prize-winning author Thomas Mann, had at first resisted democratic reform. They now felt compelled to support the Weimar Republic as the least worst alternative. They tried to steer their compatriots away from polarization to the radical Left and Right. The German nationalist Right promised to revise the Versailles Treaty through force if necessary, and such promises gained traction in respectable circles. Meanwhile, there was fear of an imminent Communist threat following the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and short-lived Communist revolutions or coups in Hungary (Bela Kun) and in Germany itself (e.g., the Sparticist Uprising). This fear shifted German political sentiment decidedly toward right-wing causes.

Agitators from the political left served heavy prison sentences for inspiring political unrest. On the other hand, radical rightwing activists like Adolf Hitler, whose Nazi Party had attempted to depose the government of Bavaria and commence a "national revolution" in the November 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, served only nine months of a five year prison sentence for treason—which was a capital offense. During the prison sentence he wrote his political manifesto, Mein Kampf (My Struggle).

The difficulties imposed by social and economic unrest following World War I and its severe peace terms, along with the raw fear of the potential for a Communist takeover in the German middle classes, worked to undermine pluralistic democratic solutions in Weimar Germany. These fears and challenges also increased public longing for a more authoritarian direction, a kind of leadership which German voters ultimately and unfortunately found in Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist Party. Similar conditions benefited rightwing authoritarian and totalitarian systems in eastern Europe as well, beginning with the losers of World War I, and eventually raised levels of tolerance for and acquiescence in violent antisemitism and discrimination against national minorities throughout the region.

Cultural Despair

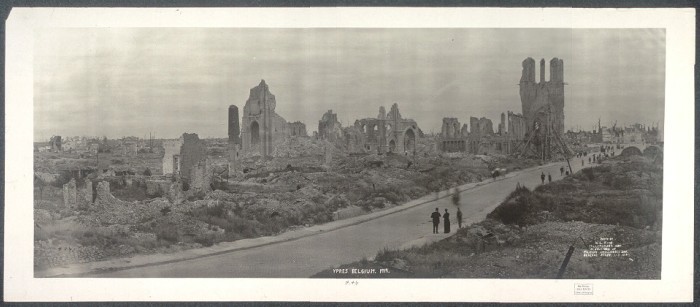

Finally, the destruction and catastrophic loss of life during World War I led to what can best be described as a cultural despair in many former combatant nations. Disillusionment with international and national politics and a sense of distrust in political leaders and government officials spread throughout the consciousness of a public which had witnessed the ravages of a devastating four-year conflict. Most European countries had lost virtually a generation of their young men.

While some writers like German author Ernst Jünger glorified the violence of war and the conflict's national context in his 1920 work Storm of Steel (Stahlgewittern), it was the vivid and realistic account of trench warfare portrayed in Erich Maria Remarque's 1929 masterpiece All Quiet on the Western Front (Im Westen nichts Neues) which captured the experience of frontline troops and expressed the alienation of the "lost generation" who returned from war and found themselves unable to adapt to peacetime and tragically misunderstood by a home front population who had not seen the horrors of war firsthand.

In some circles this detachment and disillusionment with politics and conflict fostered an increase in pacifist sentiment. In the United States public opinion favored a return to isolationism; such popular sentiment was at the root of the US Senate's refusal to ratify the Versailles Treaty and approve US membership in President Wilson's own proposed League of Nations. For a generation of Germans, this social alienation and political disillusionment was captured in German author Hans Fallada's Little Man, What Now? (Kleiner Mann, was nun?), the story of a German "everyman," caught up in the turmoil of economic crisis and unemployment, and equally vulnerable to the calls of the radical political Left and Right. Fallada's 1932 novel accurately portrayed the Germany of his time: a country immersed in economic and social unrest and polarized at the opposite ends of its political spectrum.

Many of the causes of this disorder had their roots in World War I and its aftermath. The path which Germany took would lead to a still more destructive war in the years to come.

Critical Thinking Questions

What difficulties does the government of a defeated nation face? At the conclusion of hostilities, what arrangements or support should be provided for the defeated nation?

What obligations do the victors and the world community have to the defeated enemy, if any?

Compare and contrast the treatment of Germany after WWI and after WWII, as well as the nation of Japan after WWII.