Wartime Fate of the Passengers of the St. Louis

After the denial of safe haven in Cuba and neglected appeals for entrance into the United States, the passengers of the St. Louis disembarked in Great Britain, France, Belgium, or the Netherlands. The fate of the passengers in each depended on many factors subsequently, including geography and the course of the war against Germany.

Key Facts

-

1

In each country, refugees faced uncertainty and financial hardship. At first, they were given temporary status and were often initially housed in refugee camps.

-

2

Passengers underwent experiences similar to those of other Jews in Nazi-occupied western Europe. The Germans murdered many of them in the killing centers and the concentration camps. Others went into hiding or survived years of forced labor. Some managed to escape.

-

3

Of the 620 passengers who returned to continent, 532 were trapped when Germany conquered Western Europe. Just over half, 278 survived the Holocaust. There were 254 passengers who died: 84 who had been in Belgium; 84 who had found refuge in Holland, and 86 who had been admitted to France.

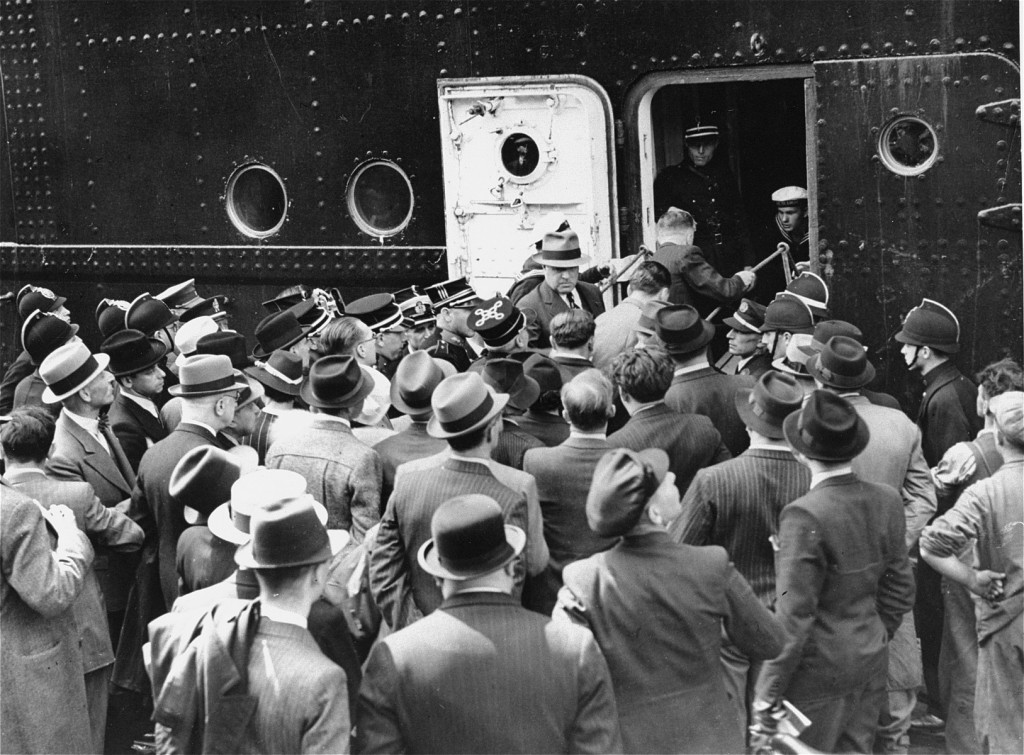

Returning to Europe

In May 1940, the German army invaded western Europe. Those Jewish refugees who had fled the Reich on the St. Louis, and who had found refuge in France and the Low Countries, were again in jeopardy.

French, Belgian, and Dutch authorities interned many thousands of German refugees, including dozens of former St. Louis passengers. British authorities interned some former St. Louis passengers on the Isle of Man and incarcerated others in camps in Canada and Australia. Many of those in Belgium and France were taken to French internment camps.

After the Vichy French authorities signed an armistice with Germany dividing France into an occupied and unoccupied zone, refugees in unoccupied Vichy France could still legally emigrate to the United States or elsewhere via Spain and Portugal. This possibility existed even after October 1941, when the Nazis banned Jewish emigration from territories they directly occupied. Some former St. Louis passengers were able to emigrate when their previously registered US immigration quota waiting list numbers were called. However, arranging such a trip was bureaucratically complicated and demanded much time and money. Anyone who wanted to go to the United States needed an immigration visa from the American consulate in Marseille, a French exit visa, and transit visas from both Spain and Portugal. Transit visas could only be obtained after booking passage on a ship from Lisbon. Some refugees, even some of the thousands still held in French internment camps, did manage to emigrate. But in 1942 these last escape routes disappeared at the very time when the Germans began to deport Jews from western Europe to the Nazi killing centers in the east.

Thus, in the end, the former St. Louis passengers underwent experiences similar to those of other Jews in Nazi-occupied western Europe. The Germans murdered many of them in the killing centers and the concentration camps. Others went into hiding or survived years of forced labor. Some managed to escape. The different fates of the Seligmann and Hermanns families illustrate the varied experiences of the passengers.

Fate of Passengers

When the St. Louis returned to Europe, the Seligmann family (Siegfried, Alma, and daughter Ursula), originally from Ronnenberg, near Hannover in Germany, settled in Brussels to await their US visas. Because they were not allowed to work, they had to depend on support from relatives and Jewish refugee organizations. When the Nazis invaded Belgium, Belgian police arrested Siegfried as an "enemy alien" and transported him to southern France, where was held in the Les Milles internment camp. His wife and daughter traveled to France to find him. They were arrested by French police in Paris and sent to the Gurs internment camp where they lived amidst conditions of deprivation and disease. Through the Red Cross, Alma and Ursula learned that Siegfried was interned in Les Milles. In July 1941, Alma and Ursula were transferred to a camp in Marseille and allowed by Vichy officials to apply for entry and transit visas to the United States. In November, the Seligmann family, then reunited, left France, traveled through Spain and Portugal, and departed from Lisbon, arriving in New York on December 3, 1941. Another daughter, Else, who had managed to reach the US via the Netherlands, was waiting for them in Washington, DC, where the family settled.

The Hermanns family was not as fortunate. Julius Hermanns, a textile merchant from Moenchen-Gladbach, had been imprisoned in Dachau and Buchenwald. After his release, he booked passage for himself on the St. Louis, but could not afford tickets and permits for his wife Grete and daughter Hilde. They remained in Germany. When the St. Louis docked in Antwerp upon returning from Cuba, Julius went to France, hoping that his family could join him there. Interned by the French as an "enemy alien," Julius was released in April 1940, but was rearrested shortly after the German invasion. Eventually, he was taken to St.-Cyprien, an internment camp near the Spanish border. Subsequently transferred to Gurs and Les Milles, the now ill Julius was unable to obtain the necessary immigration papers and visas from the American consulate in Marseille.

On August 11, 1942, French authorities sent Julius on the first prisoner transport from Les Milles to Drancy, a transit camp near Paris. Three days later, the Germans deported him to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp in German-occupied Poland, where he died. On December 11, 1941, the Germans deported Grete and Hilde Hermanns from Germany to the Riga ghetto in Latvia. They are not known to have survived the war.