Deceiving the Public

The Nazis frequently used propaganda to disguise their political aims and deceive the German and international public. They depicted Germany as the victim of Allied and Jewish aggression to hide their true ideological goals and to justify war and violence against innocent civilians.

Key Facts

-

1

Hitler and the Nazi leadership engineered a phony Polish attack on a German radio station to mask and justify their invasion of Poland.

-

2

To deflect criticism of its actions, Nazi Germany’s leadership accused the Allies and the “Jews” of spreading malicious lies and “atrocity stories.”

-

3

Nazi propagandists disguised the regime’s genocidal policies against Europe’s Jews, claiming that the Jewish population was being “resettled.”

“Common sense could not understand that it was possible to exterminate tens and hundreds of thousands of Jews,”

—Yitzhak Zuckerman, a leader of the Jewish resistance in Warsaw

Propaganda was used as an important tool to win over the majority of the German public who had not supported Adolf Hitler. It served to push forward the Nazis' radical program, which required the acquiescence, support, or participation of broad sectors of the population.

Combined with terror to intimidate those who did not comply, a new state propaganda apparatus headed by Joseph Goebbels manipulated and deceived the German population and the outside world. Propagandists preached an appealing message of national unity and a utopian future that resonated with millions of Germans. They also waged campaigns that facilitated the persecution of Jews and others excluded from the Nazi vision of the “National Community.”

Propaganda, Foreign Policy, and Conspiring to Wage War

Rearmament was a key element of German national policy after the Nazi takeover in early 1933, as it was under the democratic Weimar government. German leaders hoped to achieve this goal without causing preventive military intervention by France, Great Britain, or the states on Germany's eastern borders, Poland and Czechoslovakia. The regime also did not want to frighten a German population anxious about another European war. The specter of World War I and the deaths of 2 million German soldiers in that conflict still haunted popular memory.

Throughout the 1930s, Hitler portrayed Germany as a victimized nation, held in bondage by the chains of the post-World War I Versailles Treaty and denied the right of national self-determination.

Wartime propagandists universally justify the use of military violence by portraying it as morally defensible and necessary. To do otherwise would jeopardize public morale and faith in the government and its armed forces. Throughout World War II, Nazi propagandists disguised military aggression aimed at territorial conquest as righteous and necessary acts of self-defense. They cast Germany as a victim or potential victim of foreign aggressors, as a peace-loving nation forced to take up arms to protect its populace or defend European civilization against Communism.

The war aims professed at each stage of the hostilities almost always disguised Nazi intentions of territorial expansion and racial warfare. This was propaganda of deception, designed to fool or misdirect the populations in Germany, German-occupied lands, and the neutral countries.

Preparing the Nation for War

In summer 1939, as Adolf Hitler and his aides finalized plans for the invasion of Poland, the public mood in Germany was tense and fearful. Germans were emboldened by the recent dramatic extension of Germany's borders into neighboring Austria and Czechoslovakia without having fired a shot; but they did not line the streets calling for war, as the generation of 1914 had done.

Before the German attack on Poland on September 1, 1939, the Nazi regime launched an aggressive media campaign to build public support for a war that few Germans desired. To present the invasion as a morally justifiable, defensive action, the German press played up “Polish atrocities,” referring to real or alleged discrimination and physical violence directed against ethnic Germans living in Poland. The press deplored Polish “warmongering” and “chauvinism,” and also attacked the British for encouraging war by promising to defend Poland in the event of German invasion.

The Nazi regime even staged a border incident designed to make it appear that Poland initiated hostilities. On August 31, 1939, SS men dressed in Polish army uniforms “attacked” a German radio station at Gleiwitz (Gliwice). The next day, Hitler announced to the German nation and the world his decision to send troops into Poland in response to Polish “incursions” into the Reich. The Nazi Party Reich Press Office instructed the press to avoid the use of the word war. They were to report that German troops had simply beaten back Polish attacks, a tactic designed to define Germany as the victim of aggression. The responsibility for declaring war would be left to the British and French.

In an effort to shape public opinion at home and abroad, the Nazi propaganda machine played up stories of new “Polish atrocities” once the war began. They publicized attacks on ethnic Germans in towns such as Bromberg (Bydgoszcz). There, fleeing Polish civilians and military personnel killed between 5,000 and 6,000 ethnic Germans, whom they had perceived, in the heat of the invasion, to be fifth column traitors, spies, Nazis, or snipers. By exaggerating the actual number of ethnic German victims killed in Bromberg and other towns to 58,000, Nazi propaganda enflamed passions, providing “justification” for the numbers of civilians that the Germans intended to kill.

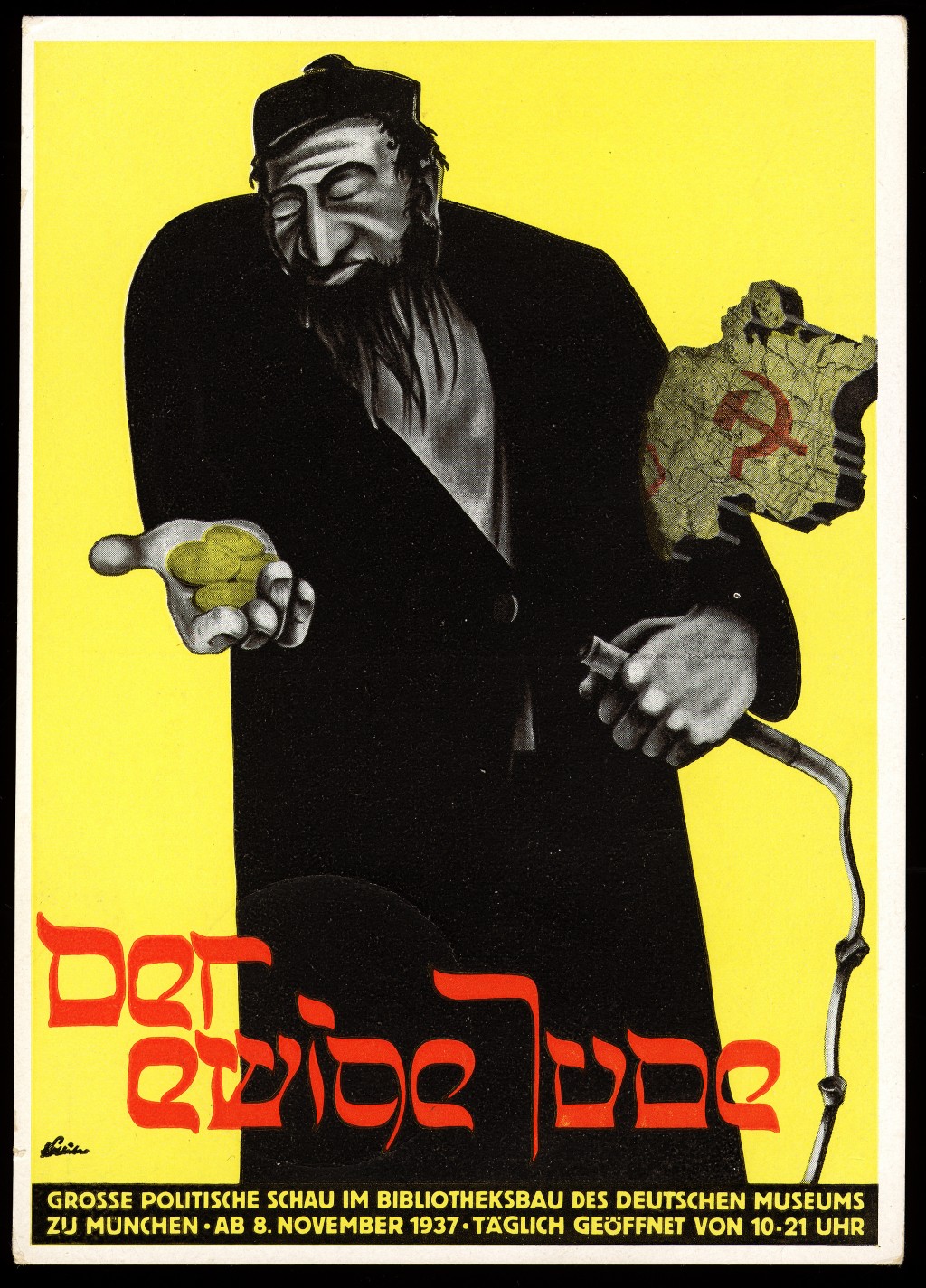

Nazi propagandists convinced some Germans that the invasion of Poland and subsequent occupation policies were justified. For many others, the propaganda reinforced deep-seated anti-Polish sentiment. German soldiers who served in Poland after the invasion wrote letters home, reflecting support for German military intervention to defend ethnic Germans. Some soldiers expressed their disdain and contempt for the “criminality” and “sub-humanity” of the Poles, and others viewed the resident Jewish population with disgust, comparing Polish Jews to antisemitic images they recalled from Der Stürmer or the exhibition entitled the “Eternal Jew,” and, later, from the film of the same name.

Newsreels also became central to German Propaganda Minister Goebbels's efforts to form and manipulate public opinion during the war. To exercise greater control over newsreel content after the war began, the Nazi regime consolidated the country's various competing newsreel companies into one, the Deutsche Wochenschau (German Weekly Perspective). Goebbels actively helped create each newsreel installment, even editing or revising scripts. Twelve to eighteen hours of film footage shot by professional photographers and delivered to Berlin each week by courier were edited down to 20 to 40 minutes. Distribution of newsreels was greatly expanded as the number of copies of each episode increased from 400 to 2,000, and dozens of foreign language versions (including Swedish and Hungarian) were produced. Mobile cinema trucks brought the newsreels to rural areas of Germany.

The Propaganda of Deception

On September 1, 1939, German forces invaded Poland. The war the Nazi regime unleashed would bring untold human suffering and losses. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in summer 1941, Nazi anti-Jewish policies took a radical turn to genocide.

The decision to annihilate the European Jews was announced at the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942 to key high-level Nazi Party, SS, and German state officials, whose agencies would contribute to implementing a Europe-wide “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.” Following the conference, Nazi Germany implemented genocide on a continental scale with the deportation of Jews from all over Europe to Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, and other killing centers in German-occupied Poland

The Nazi leadership aimed to deceive the German population, the victims, and the outside world regarding their genocidal policy toward Jews. What did ordinary Germans know about the persecution and mass murder of Jews? Despite the public broadcast and publication of general statements about the goal of eliminating “the Jews,” the regime practiced a propaganda of deception by hiding specific details about the “Final Solution,” and press controls prevented Germans from reading statements by Allied and Soviet leaders condemning German crimes.

At the same time, positive stories were fabricated as part of the planned deception. One booklet printed in 1941 glowingly reported that, in occupied Poland, German authorities had put Jews to work, built clean hospitals, set up soup kitchens for Jews, and provided them with newspapers and vocational training. Posters and articles continually reminded the German population not to forget the atrocity stories that Allied propaganda spread about Germans during World War I, such as the false charge that Germans had cut off the hands of Belgian children.

The perpetrators also hid their murderous intentions from many of the victims. Before and after the fact, the Germans used deceptive euphemisms to explain and justify deportations of Jews from their homes to ghettos or transit camps, and from the ghettos and camps to the gas chambers at Auschwitz and other killing centers. German officials stamped “evacuated,” a word with neutral connotations, on the passports of Jews deported from the Germany and Austria to the “model” ghetto at Theresienstadt, near Prague, or to ghettos in the East. German bureaucrats characterized deportations from the ghettos as “resettlements,” though such “resettlement” usually ended in death.

Nazi Propaganda about the Ghettos

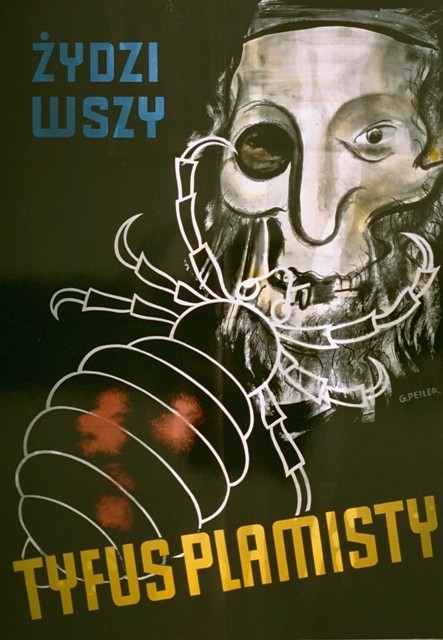

A recurrent theme in Nazi antisemitic propaganda was that Jews spread diseases.

To prevent non-Jews from attempting to enter the ghettos and from seeing the condition of daily life there for themselves, German authorities posted quarantine signs at the entrances, warning of the danger of contagious disease. Since inadequate sanitation and water supplies coupled with starvation rations quickly undermined the health of the Jews in the ghettos, these warnings became a self-fulfilling prophecy, as typhus and other infectious diseases ravaged ghetto populations. Subsequent Nazi propaganda utilized these man-made epidemics to justify isolating the “filthy” Jews from the larger population.

Theresienstadt: A Propaganda Hoax

One of the most notorious Nazi efforts at deception was the establishment in November 1941 of a camp-ghetto for Jews in Terezín, in the Czech province of Bohemia. Known by its German name Theresienstadt, this facility functioned both as a ghetto for elderly and prominent Jews from Germany, Austria, and the Czech lands, and as a transit camp for the Czech Jews residing in the German-controlled Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

Anticipating that some Germans might find the official story that Jews were being sent to the East to perform labor to be implausible in reference to elderly Jews, disabled war veterans, and prominent musicians or artists, the Nazi regime cynically publicized the existence of Theresienstadt as a residential community, where elderly or disabled German and Austrian Jews could "retire" and live out their lives in peace and safety. This fiction was invented for domestic consumption within the Greater German Reich. In reality, the ghetto served as a transit camp for deportations to ghettos and killing centers in German-occupied Poland, and killing sites in the German-occupied Baltic States and Belorussia.

In 1944, succumbing to pressure from the International Red Cross and the Danish Red Cross following the deportation of nearly 400 Danish Jews to Theresienstadt in the autumn of 1943, SS officials permitted Red Cross representatives to visit Theresienstadt. By this time, news of the mass murder of Jews had reached the world press and Germany was losing the war. As an elaborate hoax, the SS authorities accelerated deportations from the ghetto shortly before the visit, and ordered the remaining prisoners to "beautify" the ghetto: prisoners had to plant gardens, paint houses, and renovate barracks. The SS authorities staged social and cultural events for the visiting dignitaries. After the Red Cross officials left, the SS resumed deportations from Theresienstadt, which did not end until October 1944. In all, the Germans deported nearly 90,000 German, Austrian, Czech, Slovak, Dutch, and Hungarian Jews from the camp-ghetto to killing sites and centers in the “East”; only a few thousand survived. More than 30,000 more prisoners died in Theresienstadt itself, mostly from disease or starvation.

The Red Cross Visit to Theresienstadt

By 1944 most of the international community knew about the concentration camps and were aware that the Germans and their Axis partners brutally mistreated prisoners in them, but exact details about living conditions in these camps were unclear.

In 1944, Danish Red Cross officials, who, given alarming reports circulating about the fate of the Jews under Nazi rule, were concerned about the nearly 400 Danish Jews deported to Theresienstadt by the Germans in the autumn of 1943, demanded that the International Red Cross, headquartered in Switzerland, investigate living conditions in the camp-ghetto. After considerable stalling, German authorities agreed to permit a Red Cross inspection of the camp-ghetto in June 1944.

Information gathered during this investigation would be reported to the world. Newspapers in the US and throughout the world covered aspects of the Red Cross investigation.

Propaganda Film: Lens on Theresienstadt

As early as December 1943 SS officials in the Office for Jewish Emigration in Prague, an affiliate of the Reich Main Office for Security, decided to make a film about the camp. Much of it taken during the summer after the Red Cross visit, the footage depicts ghetto prisoners going to concerts, playing soccer, working in family gardens, and relaxing in the barracks and outside in the sunshine. The SS forced inmates to serve as writers, actors, set designers, editors, and composers. Many children participated in the film in return for food, including milk and sweets, which they normally did not receive.

The purpose of the mid-level officials in the RSHA in making the film is not entirely clear. Perhaps it was meant for international consumption for, in 1944, German audiences might have wondered why ghetto residents appeared to live a better, more luxurious life than many Germans in wartime. In the end, the SS only completed the film in March 1945, and never showed it. Indeed, the complete film did not survive the war.

As with other efforts to deceive the German population and the wider world, the Nazi regime benefited from the unwillingness of the average human being to grasp the dimensions of these crimes. Leaders of Jewish resistance organizations, for example, tried to warn ghetto residents of the German intentions, but even those who heard about the killing centers did not necessarily believe what they had heard. “Common sense could not understand that it was possible to exterminate tens and hundreds of thousands of Jews,” Yitzhak Zuckerman, a leader of the Jewish resistance in Warsaw, observed.

Propaganda to the Bitter End

The Soviet victory in defense of Moscow on December 6, 1941, and the German declaration of war against the United States five days later, on December 11, ensured a protracted military conflict. After the catastrophic German defeat at Stalingrad in February 1943, the challenge of maintaining popular support for the war became even more daunting for Nazi propagandists. Germans increasingly could not reconcile official news stories with reality, and many turned to foreign radio broadcasts for accurate information. With moviegoers beginning to reject the newsreels as blatant propaganda, Goebbels even ordered theaters to lock their doors before projecting the weekly episode, forcing viewers to watch it if they wanted to see the feature film.

Until the very end of the war, Nazi propagandists kept public attention focused on what would happen to Germany in event of defeat. The Propaganda Ministry particularly exploited the leak of a postwar plan for Germany's economy developed in 1944 by Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Secretary of the Treasury in the Roosevelt administration. Morgenthau envisioned stripping Germany of its heavy industry and returning the country to an agrarian economy. Such stories, which achieved some success in stiffening resistance as Allied troops moved into Germany, were aimed at intensifying fear of capitulation, encouraging fanaticism, and urging continued destruction of the enemy.

Critical Thinking Questions

What political messages, delivered through propaganda, often occur as a nation moves toward genocide?

What techniques and approaches seemed to be the most effective for the Nazi regime? What techniques and approaches seem to be effective for modern governments?

How can citizens “protect” themselves (and their nation) from propaganda in all of its forms? What institutions in a country could be involved in this effort?