Robert Ritter

Robert Ritter was a German doctor who became Nazi Germany’s leading authority on the racial classification of Roma and Sinti. In English, Roma and Sinti are sometimes referred to collectively as Roma, Romanies, or “Gypsies.” Although Ritter was not a member of the Nazi Party, his theories and his work contributed greatly to the development of the Nazi regime’s anti-Romani policies of persecution and genocide.

Key Facts

-

1

Ritter was a physician and child psychiatrist who led official efforts to register and classify Romani peoples living in Nazi Germany. His work helped facilitate the persecution and mass murder of thousands of Roma and Sinti.

-

2

Ritter was not a member of the Nazi Party, but his work supported and shaped anti-Romani policies in Nazi Germany. Nazi leaders regularly relied on the active help or cooperation of many professionals who were not necessarily convinced Nazis.

-

3

Ritter continued to work as a doctor after the end of World War II in spite of his role in the persecution of Roma and Sinti. Many people who were involved in campaigns of racial persecution under the Nazi regime escaped justice after the war and continued working in their chosen professions.

Early Life and Career

Robert Ritter was born into a middle-class, nationalist German family in Aachen in 1901. The son of a naval officer, Ritter attended school at the German army’s main military academy in Berlin. He was too young to serve in World War I (1914–1918). In 1919, he joined loosely organized rightwing paramilitary units known as Freikorps.

Ritter attended several universities in the 1920s before earning degrees in medicine and psychiatry. When he began his medical career in the early 1930s, Ritter planned to focus on the psychological study of juvenile criminal offenders. Like many medical professionals and scientists at the time, he was greatly interested in theories of eugenics. Applying these theories to his study of youth psychology, he concluded that inherited traits explained why adolescents committed crimes.

Ritter sympathized politically with some aspects of Nazi ideology, but he was not a Nazi Party member. As the party’s influence grew in the early 1930s, Ritter was critical of the Nazis’ attacks on other rightwing German nationalist groups. He supported the idea of a broader nationalist political front instead. Ritter did not join the Nazi Party after it rose to power in 1933. However, he shared the Nazis’ extreme nationalism and their enthusiasm for theories of eugenics.

Promotion of Eugenics and Forced Sterilization

Ritter became the head of the children’s division of the psychiatric clinic at the University of Tübingen in 1932. He continued to work there for several years after the Nazis came to power.

At Tübingen, Ritter diagnosed patients and created psychological profiles of juvenile criminal offenders. He also helped lead a marriage counseling center based on principles of eugenics. Proponents of Nazi racial ideology referred to eugenics as “racial hygiene” (“Rassenhygiene”). Ritter gave lectures on the topic of “racial hygiene.” He also became a member of the so-called hereditary health court in Tübingen. The 1933 Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases (Hereditary Health Law) established these courts. Their purpose was to make decisions regarding forced sterilizations. The professional opinions that German doctors like Ritter provided to the courts helped add a sense of legitimacy to Nazi Germany’s program of mass sterilization.

Early Research on Criminal Behavior and Stereotypes of Roma

Ritter theorized that criminal behavior was caused by inherited traits. He spent much of his time in Tübingen working on an academic research project that attempted to prove this theory. Ritter studied the histories of several families whose members had criminal records. He created extensive genealogical charts, tracing family histories back for ten generations. He argued that some people were born criminals and should not reproduce. Ritter’s methods were not scientific, and he ultimately failed to prove his theory. Nevertheless, the Nazi regime embraced the results of his research.

Some of Ritter’s genealogical research was focused on Romani people (sometimes referred to collectively as Roma or Romanies, or pejoratively as “Gypsies”). His theories about their supposed criminal tendencies reflected anti-Romani stereotypes that had been widespread throughout Europe for generations. As a child psychiatrist, Ritter believed he was uniquely qualified to specialize in the study of Roma. He held prejudiced views that Romani people did not develop beyond the intellectual and emotional level of adolescents, and that they should be treated as juvenile delinquents. Later in life he would write: “What could be more natural than that a child psychiatrist dealt with them, studied them, wrote about them, and made suggestions about how they should be treated?”

Ritter’s reputation as a “racial hygiene” expert grew as he presented his research to conferences of academics, police, and government officials. His genealogical research seemed to provide scientific support for Nazi sterilization policies, and it was well-received by authorities at the time. Though Ritter’s area of medical specialization had originally been youth psychology, his focus on theories of criminal biology and eugenics created new opportunities to advance his career.

Research Methods in Support of Nazi Ideology

At the beginning of 1936, Ritter was employed by the Reich Health Bureau (a department of the Interior Ministry) to lead a eugenic research group. He moved the work of his small staff to Berlin at the end of the year. Expanded funding allowed Ritter to develop this group into a new unit within the bureau: the Race Hygiene and Population Policy Research Unit (Rassenhygienische und bevölkerungspolitische Forschungsstelle).

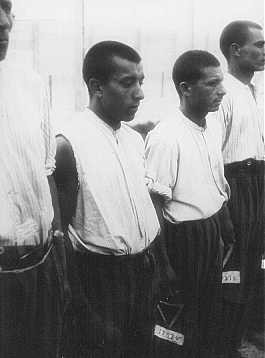

In December 1938, SS leader Heinrich Himmler issued a decree stating that the so-called “Gypsy question” (“Zigeunerfrage”) would now be dealt with “on the basis of their race.” The decree ordered Romani people to submit to physical examinations and provide evidence of their family histories.

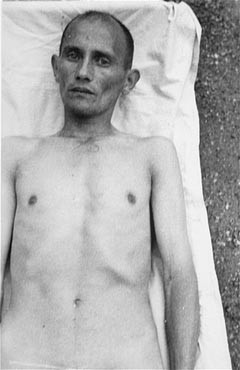

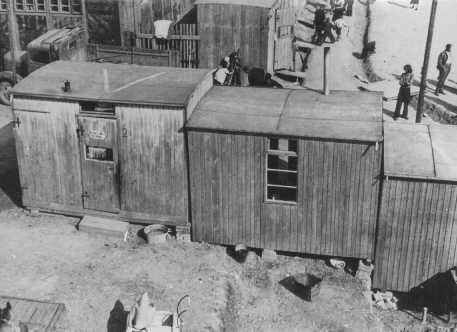

Ritter and his small staff, including his deputy Eva Justin, had first begun collecting physical and genealogical information about Roma and Sinti in 1936. Beginning in early 1938, Ritter’s team traveled to meeting places, detention centers, and the so-called “Zigeunerlager” (“Gypsy camps”) where German authorities had begun forcing Romani families to move. Ritter’s team used a combination of incentives and intimidation to gather information about the Romani people they studied. They sometimes offered them small cash bribes or threatened them with arrest or imprisonment in a concentration camp.

Ritter and his team drew upon the research methods he had developed earlier in his career. They created extensive family trees and genealogical charts to identify, register, and classify all Romani people living in Nazi Germany. As they created these charts, they collected family medical histories, marriage records, physical measurements, blood samples, birth certificates, and criminal records. A great deal of the information Ritter's team collected came from personal interviews. However, they treated this information as objective scientific data that supposedly proved Romani people were racially distinct from so-called “Aryans.”

Ritter’s team also worked closely with the Kripo (Criminal Police) to identify and register Roma and Sinti. The Kripo was the branch of the German police responsible for investigating and preventing crimes. Because the Nazi regime believed that Romani people were prone to criminal behavior, German authorities used the Kripo to target Roma and Sinti for increased policing. While other branches of the German police were also involved in the persecution of Roma and Sinti, the Kripo became the branch that was primarily responsible for enforcing anti-Romani policies and laws. Ritter helped the Kripo decide who should be classified as Romani. For years, the German police had been targeting Roma and Sinti as alleged criminals. But now Ritter’s work added another excuse to target Roma—it promoted the idea that Romani people were a racially distinct group that threatened the supposed racial purity of Germany’s so-called “national community” (Volksgemeinschaft).

Anti-Romani Prejudices and Theories about Roma and Sinti

Ritter developed theories about Roma and Sinti that closely reflected widespread anti-Romani prejudices. He thought that Romani people were born criminals. According to his eugenic theories about heredity, this made Roma and Sinti particularly likely to become so-called “asocials.” Asocial was a derogatory Nazi label for poverty-stricken and marginalized people. In addition, Ritter’s theories echoed long-standing stereotypes about the wild and adventurous spirit of Romani people. He believed in romanticized stereotypes that Roma and Sinti were “children of nature” and could not become valuable members of Nazi society.

In the 1930s, an estimated 30,000 Roma and Sinti lived in Germany. Ritter believed that the vast majority of these people were not “genuine Gypsies” but rather what he called “Zigeunermischlinge” (“Gypsy mixed-breeds”). Ritter theorized that these individuals were born criminals. He believed that relationships between Romani people and the criminal elements of European societies had created a genetically distinct group with different traits than so-called “genuine Gypsies.”

Ritter thought that those he called “genuine Gypsies” could be forced onto a reservation. There, they would be isolated from the rest of society to preserve their way of life for further study by Nazi racial scientists. But he recommended forced sterilization for those he identified as “Zigeunermischlinge.” Ritter’s theories suggested that these two groups should be treated differently. However, authorities typically applied anti-Romani policies to all those they identified as “Zigeuner” (“Gypsies”).

Ritter and the Persecution of Roma during World War II

Ritter became one of Nazi Germany’s leading authorities on the racial classification of Romani people. His theories helped drive the development of anti-Romani policies. These increasingly radical policies included segregation, sterilization, forced labor, and mass murder. Based on Ritter’s theories, people were officially classified as “Zigeuner” or “Zigeunermischlinge.” Ritter was directly or indirectly responsible for the persecution and murder of many thousands of people.

Since the mid-1930s, Ritter’s work had helped shape anti-Roma policies and the ways that German police enforced them. Ritter had worked closely with the Kripo since before the start of World War II (1939–1945). In 1941, he was appointed as head of the newly created Criminal Biology Institute of the Security Police. Ritter now worked directly for the German police on questions of Romani racial classification. The institute also provided professional opinions on the eugenic classification of young people confined to the so-called “youth protection camps” at Moringen and Uckermark. Youths aged 16 to 21 could be detained in these camps for a number of reasons. Ritter issued opinions on whether or not individual prisoners were capable of becoming productive members of Nazi society. Many imprisoned young people were forcibly sterilized based on the recommendations of the Criminal Biology Institute.

The genealogical information collected by Ritter’s team formed the basis for a registry of Romani people. Authorities used this registry to locate, arrest, and deport thousands of people. In addition, Ritter’s theories of eugenics and inborn criminal tendencies supported forced sterilizations and the segregation of Roma and Sinti into specially designated camps. Ritter believed that Romani people were a racially distinct threat to the “Aryan” race. As Nazi Germany’s policies became increasingly radical during the war, Ritter’s ideas provided pseudo-scientific rationalizations for mass murder.

Although it is difficult to establish precise numbers, scholars generally agree that at least 250,000 Romani people throughout Europe were murdered by German forces, their allies, and their collaborators during the period of Nazi rule (1933–1945).

After World War II

Shortly after the defeat of Nazi Germany and the end of World War II in Europe, Allied occupation authorities began efforts to remove Nazi influences from Germany and Austria. This process was known as denazification. Measures included the banning of the Nazi Party and its symbols, the repeal of Nazi legislation, and the arrests of top Nazi leaders. In addition, many former Nazi Party members and government officials were barred from working in certain positions. Ritter was investigated for connections to the Nazi Party. However, he presented himself as a nonpolitical public health professional. In 1946, the occupation authorities examining Ritter’s case decided he could return to his medical and academic career, largely because he had not been a member of the Nazi Party. Ritter began practicing medicine again. In 1947, he became the head of youth psychiatry in Frankfurt am Main. Many others who were not Nazi Party members but were still complicit in Nazi racial persecution also managed to return to their chosen professions after the war.

Ritter was unrepentant for the role he played in the persecution and mass murder of Roma and Sinti. He also maintained his prejudiced beliefs about Romani people’s intelligence. Ritter remained convinced that his Nazi-era work was a valuable contribution to Germany’s public health.

Several Romani survivors filed complaints against Ritter. In 1950, authorities in Frankfurt opened a preliminary investigation into his role during the Nazi era. But the case against Ritter was dismissed. A public prosecutor in Frankfurt suggested that statements made by “Gypsies” should not be believed. Ritter ultimately escaped justice. He died in 1951 after a long period of poor health.