Persecution of Roma (Gypsies) in Prewar Germany, 1933–1939

Persecution of Roma (Gypsies) in Prewar Germany and throughout Europe preceded the Nazi takeover of power in 1933. For example, in 1899, the police in the German state of Bavaria, formed the Central Office for Gypsy Affairs (Zigeunerzentrale) to coordinate police action against Roma in the city of Munich. This office compiled a central registry of Roma that grew to include data on Roma and Sinti from other German states.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, police in Germany began more rigorous enforcement of pre-Nazi legislation against Roma. The Nazis identified Roma as having “alien blood” (artfremdes Blut) and, therefore, as being racially “undesirable.” The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, one of two Nuremberg Race Laws adopted by the Nazis in September 1935, was expanded in November to include the Romani population.

A main concern for the Nazis was the systematic identification of all Romani people, whom they labeled “Gypsies.” A definition of “Gypsy,” therefore, was essential in order to undertake systematic persecution of the Romani population. To do this, the Nazis turned to “racial hygiene” (Rassenhygiene), also known as eugenics. Using this pseudo-science, they sought to determine who was Romani based on physical characteristics.

Dr. Robert Ritter, a physician at the University of Tuebingen, became the central figure in the study of Roma. His specialty was criminal biology; that is, the idea that criminal behavior is genetically determined. In 1936, Ritter became the director of the Center for Research on Racial Hygiene and Demographic Biology in the Ministry of Health and began a racial study of Roma. Ritter undertook to locate and classify by racial type Roma living in Germany, often collaborating with the police. He estimated that the Roma and Sinti population in Germany at the time was around 30,000. He performed medical and anthropometric examinations in an attempt to classify Roma. His team of researchers interviewed Roma to determine and record their genealogy, often under the threat of arrest and incarceration in concentration camps unless they identified their relatives and their last known residence.

At the conclusion of his study, Ritter declared that although Roma had originated in India and were therefore once Aryan, they had been corrupted by mingling with lesser peoples during their long migration to Europe. Ritter estimated that some 90 percent of all Roma in Germany were of mixed blood and were consequently carriers of "degenerate" blood and criminal characteristics. Because they allegedly constituted a danger, Ritter recommended they be forcibly sterilized. The remaining pure-blooded Roma, Ritter argued, should be studied further. In practice, little distinction was made between Ritter's so-called pure-blooded and mixed-blooded Roma. They all became subject to the Nazi policy of persecution and, later, mass murder.

In 1936, the Nazis centralized all police power in Germany under Heinrich Himmler, SS chief and chief of the German police. Consequently, police policy toward Roma was also centralized. Himmler relocated the Central Office for Gypsy Affairs from Munich to Berlin. In Berlin, he established the Reich Central Office for the Suppression of the Gypsy Nuisance as part of the criminal police (Kripo). This agency took over and extended bureaucratic measures to systematically persecute Roma.

Roma became subject to the Nuremberg Race Laws shortly after the laws were passed in 1935. They were also subject to the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Progeny and the Law against Dangerous Habitual Criminals. Many Roma who came to the attention of the state were required to be sterilized.

Shortly before the opening of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, the police ordered the arrest and forcible relocation of all Roma in Greater Berlin to Marzahn, an open field located near a cemetery and sewage dump in eastern Berlin. Police surrounded all Romani encampments and transported the inhabitants and their wagons to Marzahn, while others were arrested in their apartments. Uniformed police guarded the camp, restricting free movement into and out of the camp, while the criminal police (Kripo) supervised the camp itself. Many of the Roma incarcerated there continued going to work every day, but were required to return each night. Later, they were compelled to perform forced labor in armaments plants.

All over Germany, both local citizens and local police detachments began forcing Roma into municipal camps. Later, these camps evolved into forced-labor camps for Roma. Marzahn and the Gypsy camps (Zigeunerlager) set up in other cities between 1935 and 1938 were a preliminary stage on the road to genocide. The men from Marzahn, for example, were sent to Sachsenhausen in 1938 and their families were deported to Auschwitz in 1943.

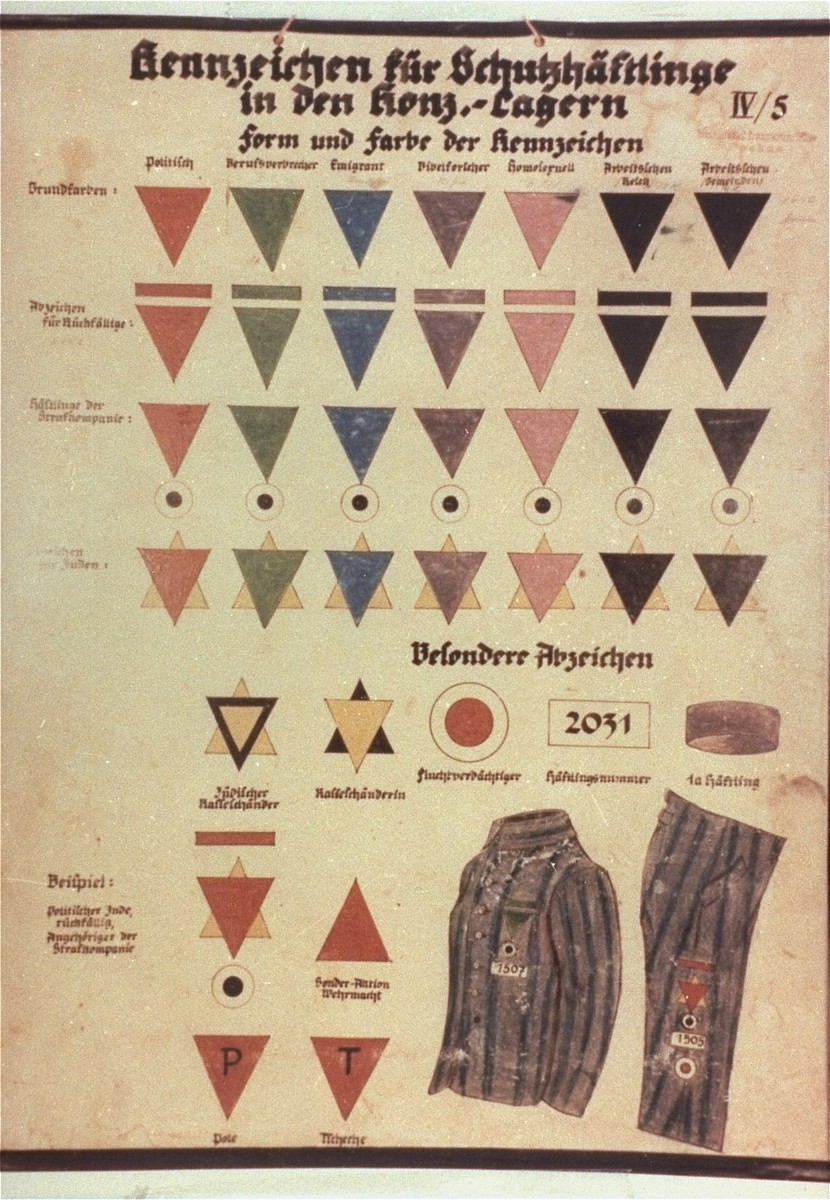

Roma were also arrested as "asocials" or "habitual criminals" and sent to concentration camps. Nearly every concentration camp in Germany had Romani prisoners. In the camps, all prisoners wore markings of various shapes and colors, which identified them by category of prisoner. Roma typically wore black triangular patches, the symbol for "asocials."