Avraham Tory

Avraham Tory (1909-2002) served as secretary of the Jewish council (known as the Ältestenrat) in the Kovno ghetto, Lithuania. He wrote a daily diary from the first days of the German invasion through the last days of the ghetto. Tory believed it was crucial to document the ghetto experience and managed the ghetto's secret archives.

Key Facts

-

1

An attorney and Zionist activist before the war, in the Kovno ghetto Avraham Tory kept a diary to document Nazi crimes. Working with others, he collected reports, armbands, German orders, and artwork, which he buried with his diary in five wooden crates.

-

2

Tory left instructions with a Lithuanian priest, Father Vaickus, that if no Jews survived the war, he should unearth the crates and forward them to the World Zionist Organization.

-

3

The diary and the other documents Tory saved helped rescue from oblivion a significant part of the history of the Kovno ghetto.

Before World War II

Tory was born Avraham Golub in 1909 in Lazdijai, Lithuania, then part of tsarist Russia. He replaced his Russian surname with a Hebrew one—both meaning “dove”—in 1950.

After attending a Hebrew high school in Marijampole, Lithuania, and participating in the General Zionist youth movement, Tory attended law school in Kovno and in the United States. Completing his law degree in Kovno, Tory worked during the 1930s as an assistant in the law office of a Jewish professor.

Soviet Annexation and German Occupation

When the Soviets annexed Lithuania in 1940, Tory was working for the Soviet construction administration that was building military bases in Lithuania. The era’s volatile politics, however, twice caused Tory to flee Kovno.

The first time, he went into hiding in Vilna (Vilnius) to escape the Soviet threat of arrest and deportation to Siberia for his Zionist “counter-revolutionary” sympathies. After the Soviets retreated in June 1941, permitting Tory to return, the dangers posed by the occupying German regime forced him to flee again. Prevented from crossing the Lithuanian-Russian border, he returned to Kovno and found himself with the rest of Kovno’s Jews caught in ghetto captivity.

Archivist in the Ghetto

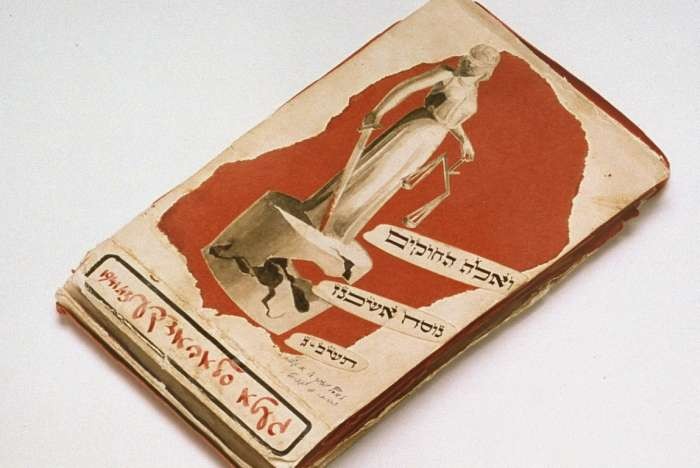

Like others, Tory began keeping a diary, writing entries at night (with the help of an assistant, Pnina Sheinzon) based on notes he took during the day. As secretary of the Jewish council (Ältestenrat), his vantage point was unique. He was able to report conversations between chairman Elchanan Elkes and Gestapo authorities. He provided the text that, in the hands of the graphic designers of the Paint and Sign Workshop, became two of the central documentary records of the ghetto: the compilation “And These Are The Laws—German Style” and the yearbook “Slobodka Ghetto 1942.”

Tory was deeply involved in administering the day-to-day affairs of the ghetto and managing its secret archives. He believed it was crucial to document the ghetto experience and used his position to commission artists and requisition images—including 150 photographs—for the archive. He also collected documents or their carbon copies from various council offices.

Escape

When the ghetto became a concentration camp in September 1943, the council’s influence with the Germans diminished. Tory searched for any possible means of escape. Because of his ties to groups outside the ghetto, he managed to spirit Pnina and her daughter, Shulamit, to safety.

Tory also made preparations to secure five small wooden crates containing his own diary, the compilation of orders, the 1942 yearbook, the Ältestenrat office reports, art, and photographs in a bunker beneath Block C, the unfinished Soviet-built apartment house that had been used for a number of open and clandestine ghetto activities. He himself then escaped on March 23, 1944, spending the final months of the war in hiding on a farm outside Kovno.

Retrieving the Archive

Immediately after the liberation of Kovno in August 1944, Tory returned to the ghetto in search of Block C, then reduced to rubble. He was able to retrieve only three of the crates he had hidden. He took their contents to Poland. There, he turned over his diary and other documents to a member of Brihah, the organization helping Jews reach Palestine, who promised its safe passage to Bucharest.

Tory himself traveled through Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Austria, and Italy, where he remained for two years. In October 1947, he arrived for good in Tel Aviv. With the help of the Israeli ambassador to Romania, Tory regained his diary and most of the cache of documents from the Kovno ghetto.

After the Holocaust

Over the years, Tory served Israel’s legal profession with distinction, achieving recognition in 1969 when he took on responsibilities as secretary general of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers.

Yet it was the publication of his diary and the preservation of other secret archive documents that made the most durable impact. Consulted by investigators as evidence against Lithuanian and German perpetrators since the 1960s, the diary serves as an extraordinary eyewitness account. It was published in Hebrew in 1988 and in English two years later in 1990 as Surviving the Holocaust: The Kovno Ghetto Diary.

The diary and the other documents Tory saved helped rescue from oblivion a significant part of the history of the Kovno ghetto.

Critical Thinking Questions

Learn about another similar effort in Warsaw, the Oneg Shabbat Archive.

Resistance comes in many forms, both violent and non-violent. Consider the many factors which may lead an individual or group to resist an oppressive regime. Investigate these factors in other periods of persecution.

What risks might a group or individual face when resisting the actions of government or society?