International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg

The trial of leading German officials before the International Military Tribunal (IMT) is the best known war crimes trial held after World War II. It formally opened in Nuremberg, Germany, on November 20, 1945, just six and a half months after Germany surrendered. Each of the four major Allied nations—the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and France—supplied a judge and a prosecution team.

Key Facts

-

1

The 24 defendants (of whom 22 stood trial) were chosen from the Nazi diplomatic, economic, political, and military leadership.

-

2

The charges against the defendants were (1) conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity; (2) crimes against peace; (3) war crimes; and (4) crimes against humanity.

-

3

Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels never stood trial, having committed suicide before the end of the war.

Background

Beginning in the winter of 1942, the governments of the Allied powers announced their intent to punish Nazi war criminals.

In October 1943, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin signed the Moscow Declaration of German Atrocities. The declaration stated that at the time of an armistice, Germans deemed responsible for atrocities, massacres, or executions would be sent back to those countries where they had committed the crimes. There, they would be judged and punished according to the laws of the nation concerned. Major war criminals, whose crimes affected more than one country, would be punished by joint decision of the Allied governments.

Though some Allied political leaders advocated summary executions of Nazi Germany’s leaders, the United States proposed to try them instead. In the words of US Secretary of State Cordell Hull, "a condemnation after such a proceeding will meet the judgment of history, so that the Germans will not be able to claim that an admission of war guilt was extracted from them under duress."

On August 8, 1945, the French Republic, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America signed the London Agreement and Charter, also referred to as the Nuremberg Charter. The Charter created an International Military Tribunal to try German leaders.

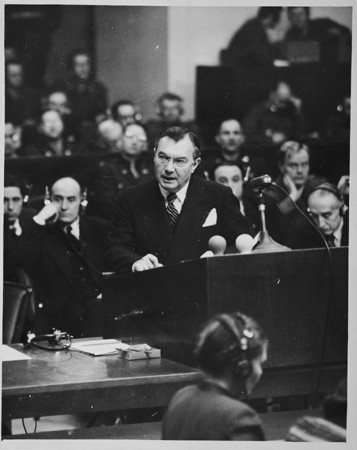

The International Military Tribunal

The privilege of opening the first trial in history for crimes against the peace of the world imposes a grave responsibility. The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant and so devastating, that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survive their being repeated.

—US Chief Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson

Opening statement before the International Military Tribunal

Each of the four countries that created the International Military Tribunal (IMT) supplied one judge, one alternate judge, and a prosecution team. The alternate judges participated in the Tribunal’s deliberations but did not have a vote in its decisions.

The Nuremberg Charter charged the IMT to conduct a fair trial and to afford the defendants certain rights. These included the right to speak and present evidence and witnesses in their own defense. It also included the right to cross-examine witnesses for the prosecution.

The Judges

Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence of Great Britain served as the court's president. This position gave him the tie-breaking vote, even though convictions and sentences required a majority vote by the four judges who heard the case. Norman Birkett was Britain’s alternate judge.

For the United States, former US Attorney General Francis Biddle served as judge. John J. Parker served as alternate judge.

France appointed Henri Donnedieu de Vabres as judge and Robert Falco as alternate judge.

Major General I.T. Nikitchenko served as the Soviet judge. Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Volchkov served as his alternate.

The Prosecution Team

US Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson played a decisive role in negotiating the Nuremberg Charter. He then served as chief prosecutor for the United States before the IMT. He also gave the opening and closing statements in the trial.

The chief prosecutors appointed by the other three countries that created the IMT were:

- François de Menthon and then Auguste Champetier de Ribes for France;

- Sir Hartley Shawcross for Great Britain; and

- Lieutenant General Roman Andreyevich Rudenko for the Soviet Union.

The four chief prosecutors worked as a committee to decide upon the defendants to be charged and to draw up the indictment.

The Charges

We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow.We must summon such detachment and intellectual integrity to our task that this Trial will commend itself to posterity as fulfilling humanity’s aspirations to do justice.

—US chief prosecutor Robert H. Jackson

Opening statement before the International Military Tribunal

Listen to an excerpt

The Nuremberg Charter defined three crimes to be tried by the IMT: crimes against peace; war crimes; and crimes against humanity. In its definition of crimes against peace, the Charter included "participation in a common plan or conspiracy" to commit crimes against peace.

On October 18, 1945, the chief prosecutors of the IMT indicted 24 leading Nazi officials on four charges related to the three crimes originally defined in the Nuremberg Charter:

- Conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity

- Crimes against peace

- War crimes

- Crimes against humanity

The Nuremberg prosecutors decided to make conspiracy to commit crimes against peace a separate charge from commiting crimes against peace. They also expanded this conspiracy charge to include conspiracy to commit war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Following the definition of the crimes laid out in the Charter, however, the IMT rejected the prosecutors’ charges of conspiracy to commit war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The indictment used a new legal term: genocide. The word had been introduced just one year earlier by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish international law expert. Under the charge of war crimes, the indictment described the "murder and ill-treatment of civilians" committed by the defendants as "deliberate and systematic genocide, viz., the extermination of racial and national groups." The IMT prosecutors repeatedly employed the term genocide during the trial, but the judges did not adopt it in their verdict.

The Defendants

After much debate, 24 defendants were chosen to represent a cross-section of Nazi diplomatic, economic, political, and military leadership. Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels could not be tried because they killed themselves at the end of the war or soon afterwards. Hermann Göring was the highest ranking Nazi official among the defendants.

In the end, only 22 defendants stood trial. German industrialist Gustav Krupp was included in the original indictment, but he was elderly and in failing health. The Tribunal decided in preliminary hearings to exclude him from the proceedings. Head of the German Labor Front Robert Ley killed himself on the eve of the trial. In the end, only 21 defendants appeared in court. Nazi Party secretary Martin Bormann could not be located. Borman was thus tried in absentia.

The indictment also charged certain Nazi Party organizations and German state and military agencies with committing crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. These were:

- the Reich Cabinet;

- the Leadership Corps of the Nazi Party;

- the Schutzstaffel (referred to as the SS, literally "protection squadron"), including the SS intelligence service, called the Sicherheitsdienst (often referred to as the SD or the Security Service of the SS);

- the Geheime Staatspolizei (known as the Gestapo or Secret State Police);

- the Sturmabteilung (referred to as the SA or Stormtroopers); and

- the General Staff and High Command of the German Armed Forces.

The Trial

The trial began on November 20, 1945, in the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany.

Over 400 visitors attended the proceedings each day. In addition, 325 correspondents representing 23 different countries were in attendance.

A team of translators provided simultaneous translations of all proceedings in four languages: English, French, German, and Russian.

Except for Martin Bormann, who could not be located, the defendants attended the proceedings. All the defendants, including Bormann and the indicted organizations, were represented by counsel.

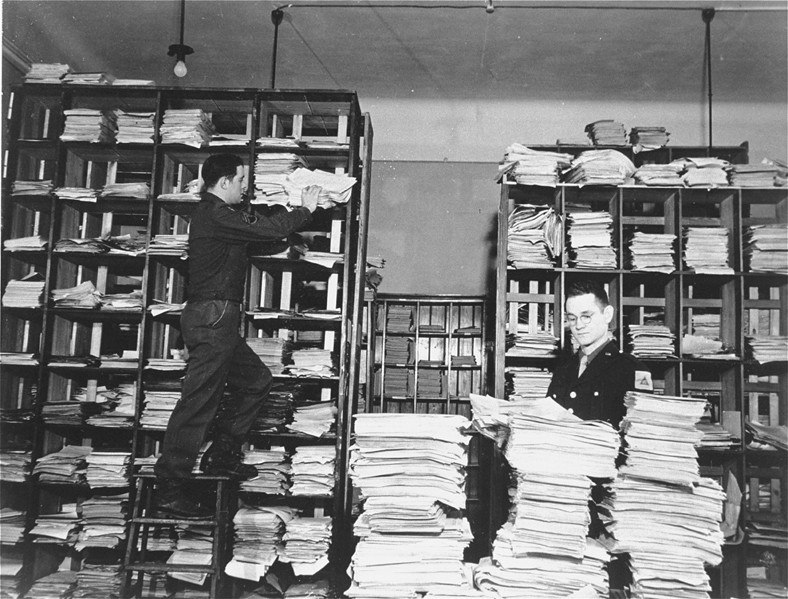

The Evidence

The prosecutors sought to prove Nazi Germany’s crimes through the Germans' own words and testimony. They based the case primarily on thousands of German documents seized by the Allies. Most of the witnesses they called to testify had been members of the Nazi Party, SS, or German state or military.

The prosecution also presented films as evidence. One film produced by the United States showed the liberation of the concentration camps. Another film produced by the Soviets showed evidence of Nazi atrocities and the liberation of Majdanek and Auschwitz concentration camps. The Holocaust was not the main focus of the trial, but considerable evidence was presented about the "Final Solution," the Nazi plan to systematically murder the Jewish people. This information included the mass murder operations at Auschwitz, the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto, and the estimate of six million Jewish victims.

The defendants did not deny the authenticity of the documentary evidence. Most acknowledged that the crimes charged did occur. However, they denied that they bore any personal responsibility for them. Under the IMT's charter, the defendants could not claim innocence on the grounds that they had simply followed orders.

The Verdict

The trial hearings ended on September 1, 1946. On October 1, 1946, the judges delivered their verdict. They convicted 19 of the defendants and acquitted three.

The judges of the IMT sentenced twelve defendants to death, including Hermann Göring and Martin Bormann.

On October 16, 1946, ten of the condemned were hanged, cremated in Dachau, and their ashes dropped in the Isar River. Hermann Göring escaped the hangman's noose by killing himself the night before. Martin Bormann, who was convicted in absentia, was much later proved to have died in Berlin during the final days of the war.

The IMT also declared the following Nazi party organizations to be criminal organizations:

- the Leadership Corps of the Nazi Party;

- the Gestapo;

- the SS; and

- the SD (SS intelligence service).

The court concluded that the criminality of SS membership did not apply to persons whose membership ceased before the start of World War II or to persons who were drafted into the SS and did not participate in its crimes.

The Nuremberg Charter's definition of crimes against humanity specified that they included acts committed "before or during the war." The IMT judges decided, however, that they could only consider crimes against humanity committed during the war. Although the judges acknowledged that Nazi Germany committed terrible crimes before the war, including the persecution of Jews, they did not judge the defendants for their role in prewar crimes.

An important legacy of the Nuremberg Charter and the IMT is that they established crimes against humanity as crimes under international law. The IMT judgment addressed the evidence proving war crimes and crimes against humanity together and did not differentiate between the two. Consequently, the judgment provided no precedent for distinguishing crimes against humanity from war crimes.

Other Trials in the Postwar Era

The IMT trial is the most famous of the war crimes trials held after World War II. During the five years that followed the end of the war, hundreds of thousands of Nazi perpetrators and their collaborators were tried by other courts in Germany and in the countries that were allied to or occupied by Nazi Germany.

The United States and the Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings: On October 17, 1946, only one day after the IMT defendants were executed, President Harry Truman appointed Telford Taylor to be the new American chief war crimes prosecutor.

Between December 1946 and April 1948, Taylor oversaw the prosecution of 185 Germans in 12 separate trials in Nuremberg for the crimes set out in the Nuremberg Charter. These trials before American military tribunals are often referred to collectively as the Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings.

Government officials, military leaders, members of the SS and Police, as well as German doctors and industrialists were tried for their roles in crimes proved before the IMT, including the persecution and mass murder of Jews and the murder of people with physical and mental disabilities in the Euthanasia Program.

Military Court Trials in Allied Occupation Zones: In addition, military courts in the British, American, French, and Soviet zones of occupied Germany, Austria, and Italy conducted thousands of war crimes trials. The overwhelming majority of the defendants in these trials were lower-level officials, officers, and soldiers as well as civilians. They included concentration camp commandants, guards, and Kapos, and German citizens who murdered Allied flyers shot down over Germany.

Trials in other Countries: Thousands of other war criminals were tried by courts in those countries where they had committed their crimes. For example, the Polish Supreme National Tribunal tried and convicted 49 leading Nazi officials for crimes committed during the German occupation of Poland.

Fleeting Justice

Within a few years of the war's end, interest in bringing Nazi criminals to justice waned. By the late 1950s, nearly all of those who had been convicted but not executed were released. Of the convicted IMT defendants who were not hanged, only one spent the rest of his life in prison: Rudolf Hess, who had been a longstanding personal aide to Adolf Hitler and deputy party leader of the Nazi Party until 1941.

Many perpetrators of Nazi crimes were never brought to trial or punished.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

The former high station of these defendants, the notoriety of their acts, and the adaptability of their conduct to provoke retaliation make it hard to distinguish between the demand for a just and measured retribution, and the unthinking cry for vengeance which arises from the anguish of war. It is our task, so far as humanly possible, to, draw the line between the two. We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow. We must summon such detachment and intellectual integrity to our task that this Trial will commend itself to posterity as fulfilling humanity's aspirations to do justice.

Critical Thinking Questions

Who was put on trial and why?

How did this trial set precedents for postwar justice?

What was the “Nuremberg defense?”