Emanuel Ringelblum and the Creation of the Oneg Shabbat Archive

Key Facts

-

1

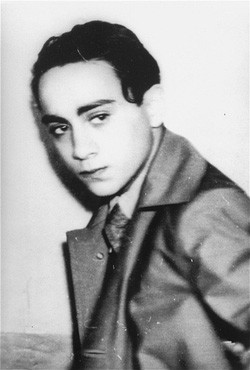

Emanuel Ringelblum (1900-1944) was a Warsaw-based historian, political activist, and social welfare worker prominent in Jewish self-aid efforts.

-

2

In the Warsaw ghetto, he founded a clandestine organization that aimed to provide an accurate record of events taking place in German-occupied Poland while the ghetto existed. This archive came to be known as the “Oneg Shabbat” (literally “Joy of the Sabbath,” also known as the Ringelblum Archive).

-

3

Only partly recovered after the war, the Ringelblum Archive remains an invaluable source about life in the ghetto and German policy toward the Jews of Poland.

Emanuel Ringelblum before World War II

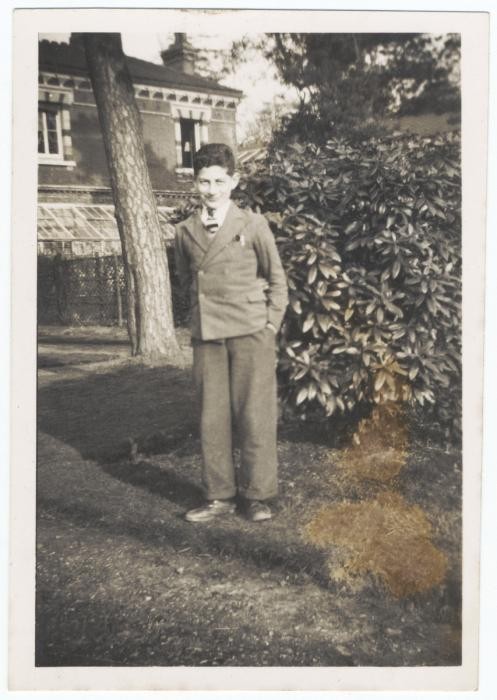

Ringelblum was born in the town of Buczacz on November 21, 1900. At the time of his birth, Buczacz was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (during the interwar era it was in Poland; today, Buchach is in Ukraine). He received his doctorate in history at the University of Warsaw in 1927. In Warsaw, he met his wife, Yehudis Herman. They had a son named Uri in 1930.

From a young age, Emanuel Ringelblum belonged to the socialist-Zionist political party, Po’alei Zion Left, and took an active role in Jewish public life, working as a high school teacher and as an employee of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) in Poland.

Ringelblum also began to develop a reputation as a serious historian of Polish-Jewish life. He formed a historical society with a group of other Polish-Jewish historians. He became one of the group’s leading scholars and an editor of the society’s publications. By 1939, he had published 126 scholarly articles on his own. This scholarly productivity foreshadowed his prolific work in the Warsaw ghetto.

In November 1938, as part of his work for the JDC, Ringelblum traveled to the Polish border town of Zbaszyn. There, 6,000 Jewish refugees from Germany, hungry and cold, were stranded on the border, denied admission into Poland after having been expelled from Germany. Ringelblum spent five weeks in Zbaszyn. He organized assistance for the refugees trapped on the border, creating a welfare office, legal section, and migration department. He also organized cultural activities.

Ringelblum’s experiences in Zbaszyn profoundly impacted him and would prepare him for his work in Warsaw during the war.

The Outbreak of World War II and the Creation of the Archive

Upon the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, Ringelblum had just returned to Warsaw from Switzerland, where he had been a Po’alei Zion Left delegate to the 21st Zionist Congress in Geneva. Although many key Jewish leaders fled the Polish capital, Ringelblum refused to leave. During the siege of Warsaw, he participated in civil defense watches under heavy fire and assisted those injured in air raids. He continued his work for the JDC, helping to organize emergency relief and refugee aid.

During the war, Ringelblum’s two major prewar endeavors—history and social welfare —came together. He became a major leader of the Jewish mutual aid organization in Warsaw, the Aleynhilf (self-help). He helped coordinate aid to refugees and soup kitchens. He also helped organize an extensive network of House Committees and tried to make them into the social base of the Aleynhilf.

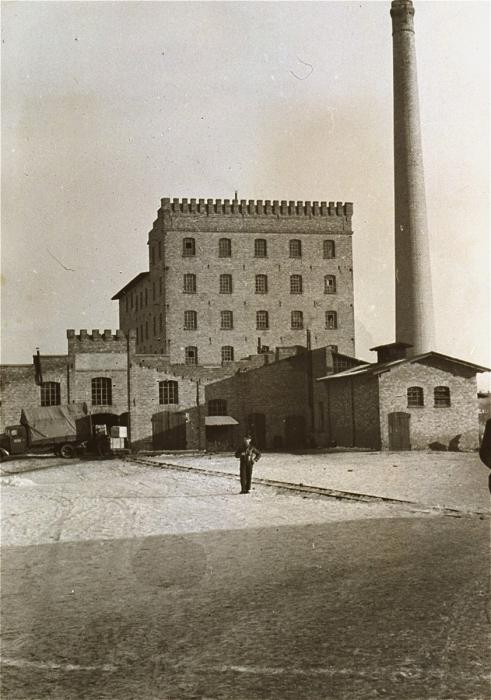

Ringelblum helped found a society for the advancement of Yiddish culture (Yidishe Kultur Organizatsye; YIKOR) in the ghetto. His most important initiative, however, was the creation of the Oneg Shabbat underground archive—the secret archive of the Warsaw ghetto. The term Oneg Shabbat, which refers to the traditional Sabbath gathering of members of the community, was applied to the underground archive because its organizers held their regular, clandestine meetings on the Sabbath. Begun as an individual chronicle by Ringelblum in October 1939, the archive grew into an organized underground operation with several dozen contributors after the sealing of the ghetto in November 1940.

The Fate of Ringelblum and the Archive

Ringelblum and his family escaped from the Warsaw ghetto in March 1943. They went into hiding in the non-Jewish section of Warsaw. He would return to the ghetto during the Warsaw ghetto uprising. Ringelblum was captured and deported to the Trawniki camp. After escaping with the help of a Polish man and a Jewish woman, he returned to his family in hiding. Their hiding place was discovered in March 1944. The family and the other Jews they had been in hiding with were taken to the ruins of the Warsaw ghetto and killed there.

Tragically, only the first two parts of the archive were found after the war. They are preserved in the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, and constitute one of the most important collections of documentation about the fate of Polish Jewry in the Holocaust.

Critical Thinking Questions

What aims may have influenced Ringelblum in his decision to create an archive of life in the Warsaw ghetto?

What may have motivated Ringelblum and the other workers of the Oneg Shabbat archive to continue to collect materials, despite the constant risk of danger?

Investigate what types of materials were preserved in the Oneg Shabbat archive. What can these materials teach us about Jewish life in the ghetto?