Esther Lurie

While confined in the Kovno ghetto, several artists drew and painted portraits and landscapes. They were even made to create copies of art masterpieces for the German overseers and others stationed in Kovno. In addition, they worked secretly to capture scenes of violence and deportations. Among these artists was Esther Lurie.

Early Years

Esther Lurie was born in 1913 in the city of Liepaja, Latvia. As a young student in Latvia’s capital, Riga, she was interested in drawing and design. Upon graduation from the Hebrew gymnasium, Lurie joined her brother in Brussels. She enrolled in a practical arts school to study theater design. To obtain more formal training, she moved on to the fine arts academy in Antwerp (the Academie Royale des Beaux Arts).

In 1934, Lurie joined part of her family in Tel Aviv. They had settled there a few years earlier. Lurie became a set designer for theatrical companies. By 1938 she had exhibited her paintings in Jerusalem and Haifa. She also won the city of Tel Aviv’s coveted Dizengoff Prize.

Toward the end of 1938, Lurie returned to Antwerp for more training. As war threatened western Europe, Lurie went east in the fall of 1939. She joined her sister in Kovno, Lithuania.

In the Ghetto

Lurie was ultimately caught in the expanding net of Nazi terror after German forces occupied Lithuania. All the Jews in Kovno were confined in a ghetto.

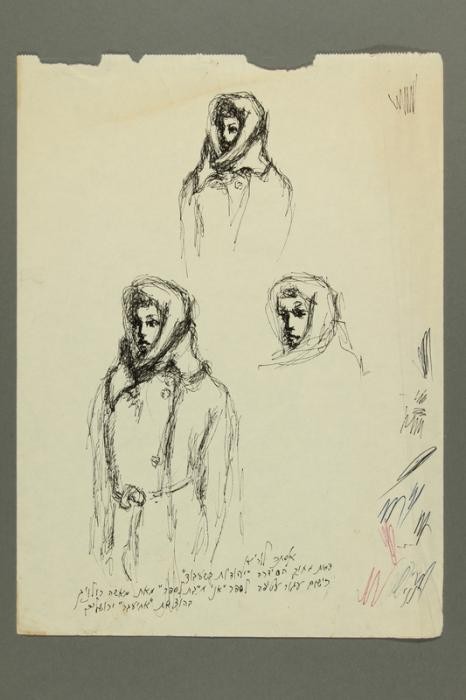

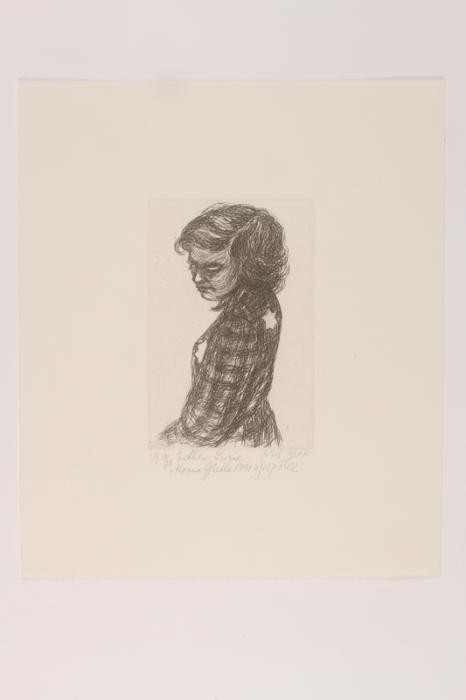

Drawing was Lurie’s first sustained response to the confusion of the ghetto’s early days. She depicted displaced families trying desperately to set up living quarters. Families even sought space among heavy machinery and industrial equipment in a former school of handicrafts. Other works by Lurie capture the misery and desperation of this period. These images include one of a girl and another of a group, all wearing the yellow star.

Lurie's portrait of starving ghetto inhabitants frantically raiding the potato field in search of food sparked the Jewish council’s interest in her work. Jewish council chairman Elkhanan Elkes eventually granted Lurie a temporary work release. She also received a commission to document life in the ghetto for its secret archives. By fall 1942 she was working regularly with fellow artists, including several from the Paint and Sign Workshop in the ghetto.

Lurie often showed crisis within ordinary, even quiet settings. She illustrated Demokratu Square in empty stillness, the scene of a massive, murderous “selection.” In a series of watercolors and pen-and-ink drawings, she showed faint figures passing peaceful suburban houses on the way to the Ninth Fort–a killing site.

Artist Jacob Lifschitz worked with Lurie for the secret archiving project. He eventually became Lurie’s greatest collaborator. Artist Josef Schlesinger was also active in the ghetto and was closely associated with Lurie. Although little is known about him, Ben Zion (Nolik) Schmidt also worked in the ghetto’s graphics shop. His 1942 depiction of the expulsion of Jews from Demokratu Square is the only surviving drawing he produced.

Lurie herself was deported in July 1944 to the Stutthof concentration camp. She endured several forced-labor camps until her liberation in January 1945.

After the War

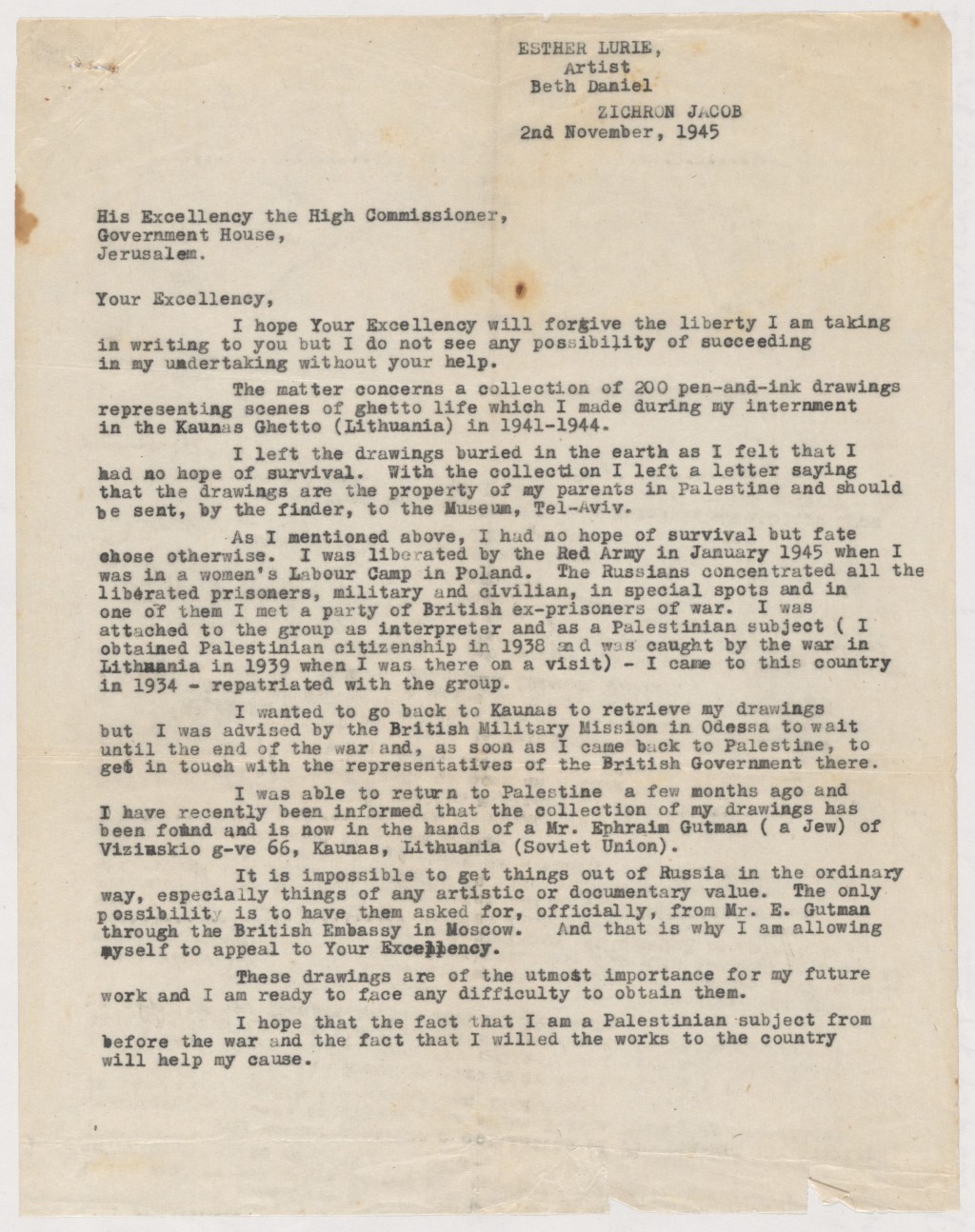

Most of the Kovno ghetto artists’ work was lost. The majority of Lurie’s 200-plus watercolors and sketches have never been found. They were probably destroyed, even though she had buried the works in ceramic jars for safekeeping during the October 1943 deportation to Estonian labor camps. The small portion that did survive includes several sketches and portraits that Avraham Tory buried in secret crates. Eight watercolors and additional portrait sketches were found hidden with the Paint and Sign Workshop’s archive.

After liberation, Lurie stayed briefly in Italy. She exhibited her forced-labor camp drawings there before returning to Israel. She spent much of her time after the war reconstructing her ghetto artwork. To do this, she used photographs Tory had taken of her pictures during a clandestine exhibition. In the 1970s, five pen-and-ink drawings, scenes of deportation, were discovered by a Lithuanian family and returned to the artist.

Lurie resided in Tel Aviv until her death in 1998.

Critical Thinking Questions

Why do you think Jewish residents of the Kovno ghetto established a secret archiving project?

How can the arts serve as a form of resistance?

Why are firsthand accounts and documentation of mass atrocity important?