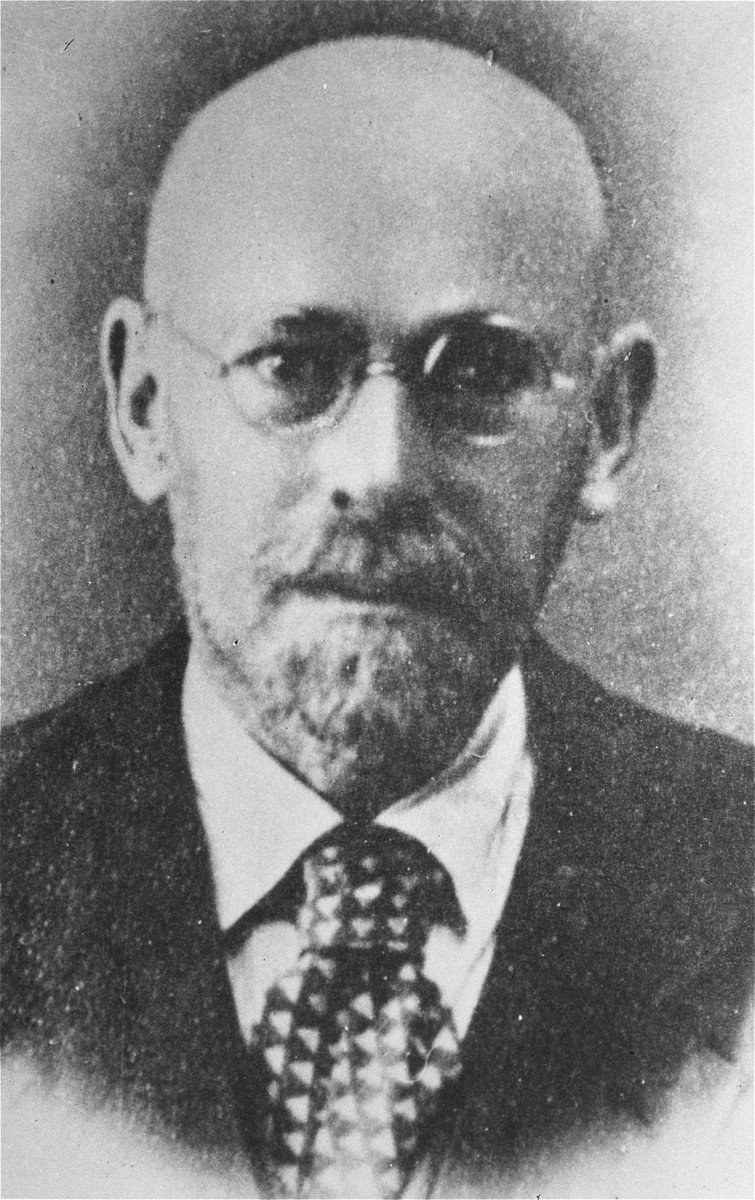

Janusz Korczak

Janusz Korczak was a well-known doctor and author who ran a Jewish orphanage in Warsaw from 1911 to 1942. Korczak and his staff stayed with their children even as German authorities deported them all to their deaths at Treblinka in August 1942.

Janusz Korczak was the pen name of Henryk Goldszmit, a Polish Jewish doctor and author. Goldszmit first gained fame in the early 1900s writing storybooks for children and childcare books for adults. Born into a highly assimilated Polish Jewish family in Warsaw in the late 1870s, Goldszmit trained as a pediatrician. He developed groundbreaking views on raising children, urging adults to treat them with both love and respect. As his reputation as an author grew, Goldszmit became known throughout Poland as Janusz Korczak.

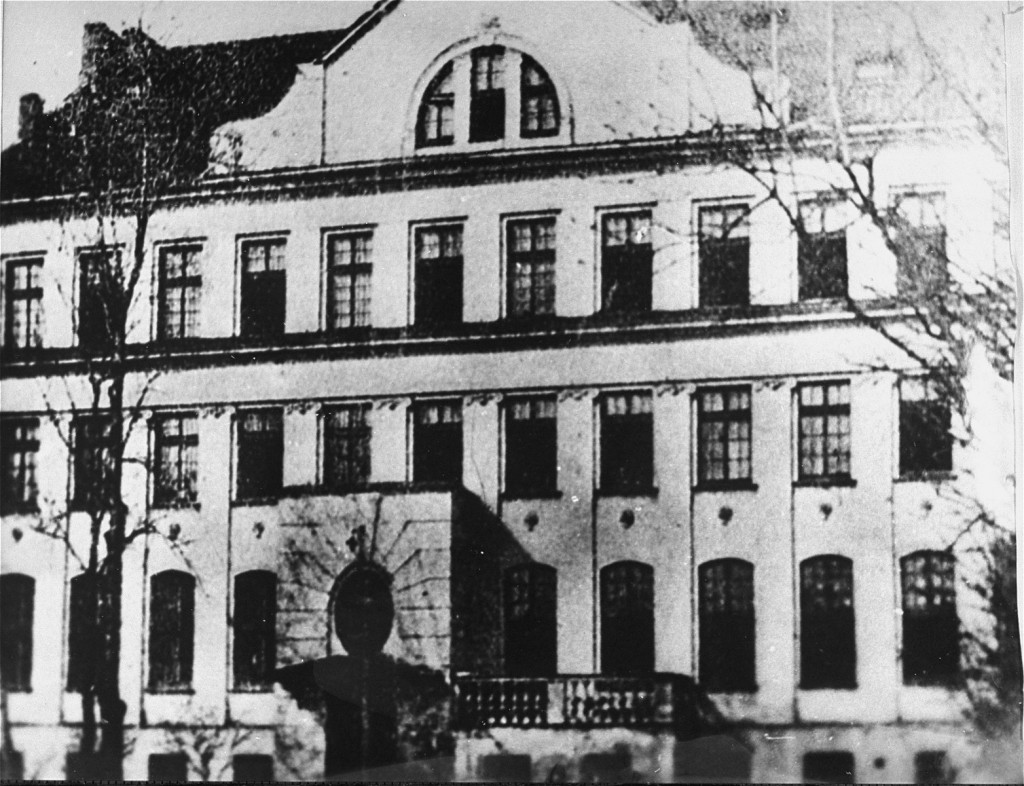

In 1911, Korczak took a position leading a new Jewish orphanage in Warsaw. For decades, he and his close colleague, Stefania "Stefa" Wilczyńska, operated the children’s home according to Korczak’s philosophies on raising children. Every child in the home had duties and rights, and everyone was responsible for their actions. The home itself was run as a “children’s republic.” The young residents regularly convened a court to hear grievances and dispense justice.

Korczak also gave the children of the home central roles in the production of Mały Przegląd (The Little Journal). Mały Przegląd was a regular supplement published in the Polish-language Zionist newspaper, Nasz Przegląd (Our Journal). Unlike many other children’s periodicals at the time, the children themselves chose the topics they wrote about and determined what would appear in the pages of their newspaper.

Korczak’s national profile grew as he began making radio broadcasts as “the Old Doctor.” He read stories, interviewed children, and lectured in a casual style that made his weekly show popular with both children and adults. Rising antisemitism in Poland in the mid-1930s caused Korczak to lose this position. However, he briefly made regular broadcasts again during the weeks following the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. Korczak tried to encourage and reassure his listeners until the partition of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union later that month.

In fall 1940, German authorities created the Warsaw ghetto. The Jewish community was forced to pay for the construction of a wall that separated the area from the rest of the city. Conditions in the overcrowded and undersupplied ghetto were extraordinarily difficult. Starvation and disease caused dozens of thousands of deaths, leaving many children orphaned and unattended.

Korczak’s ghetto diary records his constant struggles to provide food and medicine for the growing number of children under his care. Although he was beginning to struggle with his own health, Korczak spent much of his time seeking donations and carrying food back to the children’s home. His diary also describes how he tried to preserve the children’s mental and emotional well-being. The small staff did their best to maintain some semblance of the home’s normal, daily routine even in the miserable conditions of the ghetto. They kept the children focused on their studies and organized lectures, concerts, and theatrical performances.

In late July 1942, German authorities began the mass deportation of hundreds of thousands of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to their deaths at the Treblinka killing center. Korczak’s Polish friends outside of the ghetto offered to help him escape the deportations by hiding him or providing him with false identity documents. Korczak would not consider leaving, however. He and his staff decided they would not attempt to save themselves. Rather, they would continue taking care of the children for as long as they possibly could.

In early August 1942, German authorities deported the residents of all children’s homes within the Warsaw ghetto. On the morning of August 5 or 6, German police suddenly arrived and ordered Korczak’s staff to evacuate their building. Korczak, Wilczyńska, and the rest of the small staff quickly assembled the children outside. With their dedicated caretakers assisting them, nearly two hundred children walked through the crowded streets of the ghetto to the Umschlagplatz (deportation site). Korczak and the staff tried to keep the children from panicking. Witness accounts describe the group’s march through the ghetto as orderly and dignified.

After they arrived at the Umschlagplatz, Korczak and his staff boarded train cars along with the children. These trains carried deportees to the Treblinka killing center, which was located roughly sixty miles northeast of Warsaw. Conditions in these hot and overcrowded cattle boxcars were extremely dangerous for the malnourished and ill people packed tightly inside. Many individuals died on these deportation trains. Virtually all of the Jews who survived the deadly journey from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka in the summer of 1942 were murdered shortly after their arrival. The children and their caretakers were almost certainly all killed the day they arrived at Treblinka.

Janusz Korczak’s career as an author, a doctor, and a champion of children’s rights continues to inspire educators and childcare experts today. Korczak was equally proud of his Polish nationality and his Jewish identity. He is celebrated by Polish and Jewish communities alike for his life’s work and the sacrifices he made for the children in his care.

Critical Thinking Questions

How did life in the Warsaw ghetto affect children? Why were they especially vulnerable?

What new challenges did Korczak and his staff face because of conditions in the ghetto? How did they respond?

How did the Holocaust affect the traditional roles of medical providers and caregivers?

Korczak kept a diary and arranged to preserve it before his deportation. What might personal primary sources like Korczak’s ghetto diary reveal that other historical sources do not?