The Gestapo: Overview

The Gestapo was Nazi Germany’s infamous political police force. Over the course of the Nazi era, the institution of the Gestapo expanded and changed. The groups targeted by the Gestapo shifted with the regime’s policies and priorities. One thing remained consistent: the Gestapo was a reliably brutal tool that enforced Nazism’s most radical impulses.

Key Facts

-

1

As Nazi Germany’s political police force, the Gestapo was responsible for protecting the regime from its supposed racial and political enemies.

-

2

The Gestapo used informants, surveillance, house searches, and brutal interrogation methods, including torture, to carry out its investigations.

-

3

One of the Gestapo’s main responsibilities was coordinating the deportation of Jews to ghettos, concentration camps, killing sites, and killing centers.

The Gestapo was the political police force of the Nazi state.

The name Gestapo is an abbreviation for its official German name “Geheime Staatspolizei.” The direct English translation is “Secret State Police.”

The Gestapo was not the first political police force in German history. Germany, like many countries in Europe, had a long history of political policing.

Political policing is a specific type of police work. Its goal is to maintain the political status quo. Political police forces protect a state or government from subversion, sabotage, or coup. They use surveillance and intelligence gathering. These methods help them identify domestic threats against the government. Political police forces are sometimes referred to as “secret police.” Authoritarian states, such as the Nazi regime, often rely on them to maintain and protect their power.

The Gestapo as a Symbol of Nazi Brutality

The Gestapo became infamous for its brutality. Today, the institution and its political policemen are symbols of authoritarian policing.

The word “Gestapo” is often mistakenly used as a catchall for multiple groups of Nazi perpetrators. In reality, the Gestapo was just one of many institutions that perpetrated Nazi crimes. Other German police forces were also perpetrators of the Holocaust. This included the criminal police (Kripo) and the uniformed Order Police.

The Gestapo earned its infamous reputation. Gestapo policemen used torture and violence in interrogations. They coordinated the deportation of Jews to their deaths. And they harshly repressed resistance movements in Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

Political Policing during the Weimar Republic

Before the Nazis came to power in 1933, Germany was a democracy called the Weimar Republic (1918-1933). The country was a federation made up of states. These states included Prussia, Bavaria, and Saxony. Most of these states had their own political police forces.

The Weimar Republic’s constitution guaranteed individual rights and legal protections. These included: freedom of speech; freedom of the press; and equality before the law. Political police forces had to respect these rights. The constitution prevented them from conducting arbitrary police actions. Nevertheless, political policemen were active during the Weimar Republic.

In particular, the political police focused on containing political violence among the anti-democratic movements of the extreme right and left. This included policing the Nazi Party and the Communist Party. Both parties became increasingly popular in Germany beginning in 1930. Over the next three years, the Weimar-era political police struggled to respond to these often violent mass movements.

Nazifying the Political Police

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. Hitler and other Nazi leaders planned to establish a dictatorship. They also planned to eliminate all political opposition. The new Nazi regime intended to use Germany’s political police to accomplish these goals. However, there were some obstacles to overcome.

Obstacles to Nazifying the Political Police

Initially, there were two main obstacles:

- First, the Weimar Republic’s constitution remained in effect. It contained legal protections against arbitrary police actions.

- Second, Germany’s political police forces were decentralized. They remained subordinate to various state and local governments. The police did not answer to Hitler as chancellor.

These two obstacles limited how Hitler and the Nazi regime could legally use the political police. For example, in the first weeks of the Nazi regime, the Nazis could not simply order the political police to arrest Communists without a legal basis. But this quickly changed.

Overcoming Legal Obstacles

Beginning in February 1933, the Nazi regime used emergency decrees to transform Germany. These decrees freed the political police from legal and constitutional limitations. The most important of these was the Reichstag Fire Decree. It was issued on February 28, 1933. This decree suspended individual rights and legal protections, such as the right to privacy. This made it easier for the police to investigate, interrogate, and arrest political opponents. Police could now read private mail, secretly listen to telephone calls, and search homes without warrants.

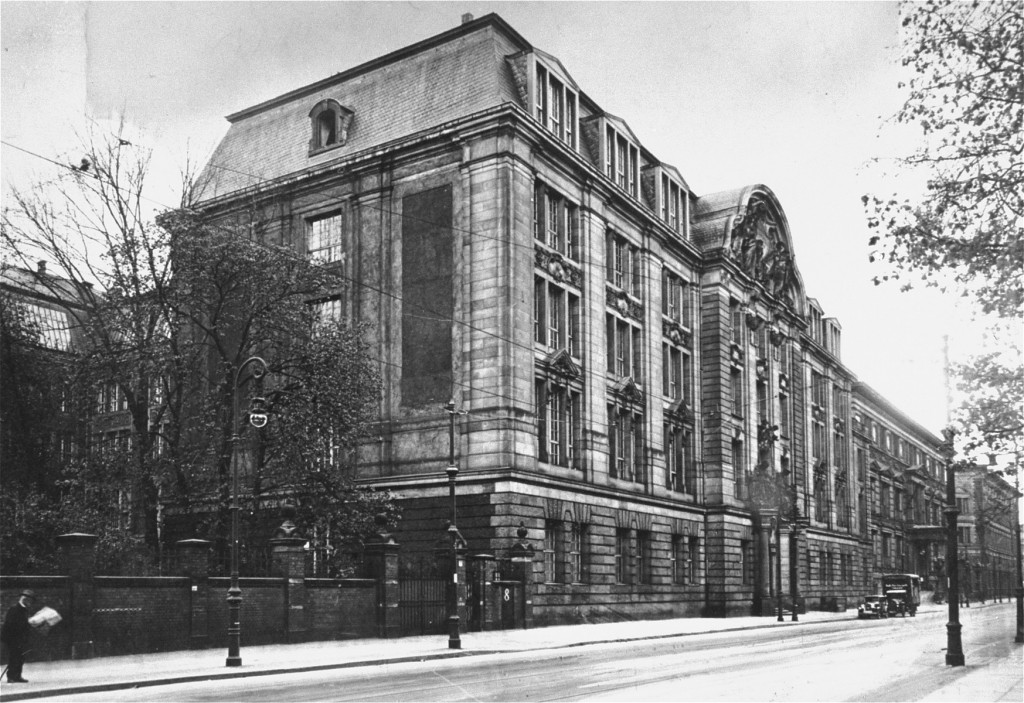

Creating the Gestapo

The Nazi regime wanted to establish a centralized political police force that would answer directly to Nazi leadership. To create this, they had to reform the existing decentralized police system. This process took several years. It included Nazifying the entire police system.

In the early 1930s, political policing remained tied to local governments. Thus, it was subject to local power struggles. By the end of 1936, however, the Nazi regime had created a strong, centralized political police force under SS leader Heinrich Himmler. This political police force was the Gestapo.

The position of the Gestapo was further strengthened in the summer of 1936. At that time, it was combined with the criminal police (Kripo). Together they formed a new organization called the Security Police (SiPo). Himmler’s deputy Reinhard Heydrich led the Security Police. Heydrich also led the SS intelligence service (Sicherheitsdienst or Security Service). This office was referred to by its German abbreviation “SD.”

In September 1939, the Security Police was officially united with the SS intelligence service (SD). Together, they became a new office called the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA). The Gestapo became Office IV of the RSHA. It was still referred to as the Gestapo.

Who worked for the Gestapo?

The Gestapo was staffed by plainclothes policemen, often called Gestapo agents. Most of these men were professionally trained. They often had worked as detectives or political policemen during the Weimar Republic. For instance, Heinrich Müller had worked for the police in Munich since 1919. He went on to become the head of the Gestapo in 1939. Professionally trained policemen like Müller brought experience, knowledge, and skill to the Gestapo.

But not all Gestapo agents were longtime policemen. Some came to the Gestapo through the SS intelligence service (SD). These SD men were Nazi ideologues with little or no police training. They were hired as part of SS leader Heinrich Himmler’s plan to transform the police system into an ideologically-driven institution.

The Gestapo united the knowledge of professional policemen with the zeal of Nazi ideologues.

What was the Gestapo’s Mission?

The Gestapo’s mission was to “investigate and combat all attempts to threaten the state.” In the Nazi view, threats to the state encompassed a wide variety of behaviors. These behaviors included everything from organized political opposition to individual critical remarks about the Nazis. The government even defined belonging to certain categories or groups of people as threatening. To combat this wide array of potential threats, the Nazi dictatorship gave the Gestapo enormous power.

One way in which the Gestapo carried out its mission was by enforcing new Nazi laws. Some of these laws broadly defined criticism of the regime as a security threat. For example, a December 1934 law made it illegal to criticize the Nazi Party or the Nazi regime. Telling a joke about Hitler could be categorized as a “malicious attack against the state or the Party.” It could then result in an arrest by the Gestapo, trial before a special court, and even imprisonment in a concentration camp.

But the Gestapo went much further than monitoring individual behaviors. They implemented Nazi ideology, which defined entire groups of people as racial or political enemies. Membership in the Communist Party or a Jewish background was enough to make someone a threat to the state and subject to Gestapo attention.

During the 1930s, the vast majority of Aryan Germans did not encounter or even expect to encounter the Gestapo. But the Gestapo was a constant threat for political opponents, religious dissenters (including Jehovah’s Witnesses), homosexuals, and Jews.

Empowering the Gestapo with Protective Custody

The Nazi regime gave Gestapo agents a great deal of power to decide the fate of the people they arrested.

Most notably, the Gestapo had the power to send people directly to a concentration camp. This was called “protective custody” (Schutzhaft). Protective custody allowed the Gestapo to bypass the court system. Those placed in protective custody could not consult a lawyer, appeal their sentence, or defend themselves in court. The Gestapo even used protective custody to override court decisions in some cases. Typically they did so when they considered the court’s sentence too lenient.

As an institution, the Gestapo was not subject to legal or administrative oversight. This meant that no other institution (including the courts) could overrule the Gestapo’s decisions. The Gestapo had the final word.

How did the Gestapo Work?

The Gestapo fulfilled their mission in a radical way. In Nazi Germany, they used common police investigation methods. However, they did so without legal limits. They pursued denunciations from the public. They carried out arbitrary searches. And they conducted brutal interrogations. In the end, Gestapo agents held the fate of the people they arrested in their hands.

Denunciations

Sometimes, the Gestapo initiated investigations themselves. At other times, the Gestapo received tips from the public. A neighbor, acquaintance, colleague, friend, or family member could inform the Gestapo that a person was behaving illegally or suspiciously. Other police forces and Nazi organizations could also inform the Gestapo of a potential crime or threat.

In Nazi Germany, these types of tips were referred to as denunciations. They were often motivated by ideology, politics, or personal gain. The consequences for those people who were denounced could be severe.

Arbitrary Searches and Surveillance

During the course of an investigation, Gestapo officers interviewed witnesses, searched homes and apartments, and conducted surveillance. In Nazi Germany, there were no limits to these activities. The Gestapo did not need a warrant to read a suspect’s mail, enter a home, or listen to telephone conversations.

Many people feared Gestapo surveillance. In reality, the Gestapo had limited personnel and only used these methods in specific cases. There was no widespread surveillance of the German population. This was why denunciations were so important.

Interrogations

The Gestapo was infamous for the ruthless ways it carried out interrogations. Gestapo officers regularly used intimidation, and psychological and physical torture. It was common for Gestapo officers to beat detainees in custody. Despite the Gestapo’s brutal interrogation methods, they did not often personally kill those whom they arrested. However, some people did die during interrogations or in Gestapo custody.

Deciding the Fate of Those Arrested

Gestapo agents had the power to determine people’s fates. Individual agents could choose to be lenient. They could let people go, dismiss cases, or issue warnings and fines.

But Gestapo agents could also choose to be ruthless. They could detain someone in prison indefinitely or condemn someone to a concentration camp. The only monitoring of these decisions came from within the Gestapo itself.

The Gestapo and the Jews Before the War

The Nazis considered Germany’s Jews a racial threat to the German people and the Nazi regime. Therefore, the Gestapo was responsible for policing Jews as part of its mission to defend the state. This became increasingly important in the second half of the 1930s.

In the first two years of the Nazi regime, the Gestapo did not focus on policing Germany’s Jewish population. At that time, the Gestapo’s priority was policing political opponents. The Gestapo did arrest some Jews in 1933 and 1934. However, these Jews were typically detained because they were Communists or Social Democrats. The Gestapo considered them political opponents.

The Nuremberg Laws and Race Defilement

The Gestapo’s involvement in anti-Jewish measures began to change with the passage of the Nuremberg Laws in fall 1935. These laws banned future marriages between Jews and non-Jewish Germans (meaning those that the Nazis considered “people of German blood”). They also criminalized extramarital sexual relationships between Jews and non-Jewish Germans. The Nazis called this crime “race defilement” (Rassenschande).

In response to the new laws, Gestapo offices throughout Germany established specialized Jewish Departments (Judenreferate). One of their responsibilities was investigating cases of race defilement.

Emigration and the “Jewish Question”

The Gestapo’s Jewish Departments also kept track of Jewish emigration. In the 1930s, the Nazi state considered Jewish emigration to be the best way to solve Germany’s “Jewish question.” The Gestapo worked to help coordinate and speed up many aspects of the emigration process. This was their way of dealing with the supposed Jewish threat to the Nazi regime. In particular, the Gestapo’s Jewish Departments worked to ensure that Jews’ financial assets remained behind and were transferred to the Nazi state.

The Gestapo at War

The most notorious and deadly Gestapo crimes took place from 1939-1945 during World War II.

During this time, the Gestapo carried out a variety of tasks at home in Nazi Germany and abroad in German-occupied territories. These tasks were supposed to guarantee the security of the Nazi regime. The war radicalized the role of the Gestapo. When Gestapo agents deployed to German-occupied territories, they behaved brutally and with impunity against the local populations.

During the war, the Gestapo:

- Investigated and harshly punished civilians who undermined the war effort or challenged the regime

- Joined the Einsatzgruppen and perpetrated mass shootings of Jews and others

- Policed foreign forced laborers in Germany and in German-occupied territories

- Repressed resistance movements in Germany and in German occupied-territories

- Organized deportations of Jews from across Europe to ghettos, concentration camps, killing sites, and killing centers.

Critical Thinking Questions

Why did the Gestapo officers initially target mainly political enemies of the Nazis, such as communists, social democrats, liberals, and other targets, and not Jews?

Why might the development of an internal political police force be a warning sign for mass atrocity?