The British Policy of Appeasement toward Hitler and Nazi Germany

Appeasement is a diplomatic strategy. It involves making concessions to an aggressive foreign power in order to avoid war. It is most commonly associated with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, in office from 1937 to 1940. In the 1930s, the British government pursued a policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany. Today, appeasement is usually regarded as a failure because it did not prevent World War II.

Key Facts

-

1

Appeasement was a pragmatic strategy. It reflected British domestic concerns and diplomatic philosophy in the 1930s.

-

2

The Munich Agreement is the best known example of appeasement. It was signed by Britain, France, Germany, and Italy in 1938.

-

3

The strategy did not stop Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. They were determined to conquer territory and wage war.

Appeasement is a diplomatic strategy. It means making concessions to an aggressive foreign power in order to avoid war. The best known example of appeasement is British foreign policy towards Nazi Germany in the 1930s. In popular memory, appeasement is primarily associated with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (in office, 1937–1940). However, appeasement of Nazi Germany was also the policy of his predecessors, James Ramsay MacDonald (1929–1935) and Stanley Baldwin (1935–1937).

In the 1930s, British leaders pursued appeasement because they wanted to avoid a second world war. World War I (1914–1918) had devastated Europe and caused the deaths of millions. Catastrophic wartime losses had left Britain psychologically, economically, and militarily unprepared for another war in Europe.

British policy towards the Nazis was especially important because of Britain’s international position. Britain was one of the world’s great powers—if not the great power—in the 1920s and 1930s. Twenty-five percent of the world's population was governed by the British Empire. And, in the 1930s, twenty percent of the Earth’s landmass was under British control.

The Nazi Threat to European Peace

As leader of Nazi Germany (1933–1945), Adolf Hitler pursued an aggressive foreign policy. He disregarded international borders and agreements that had been established following World War I.

The Nazis wanted to restore Germany to great power status by overturning the Treaty of Versailles. The treaty had tried to limit Germany’s economic and military power. It held Germany responsible for World War I and forced the Germans to pay war reparations. The treaty also reduced German territory and limited the size of the German military. The Nazis planned to rebuild the German military and reacquire lost territories. But, Hitler and the Nazis planned to go much further than simply overturning the Treaty of Versailles. They wanted to unite all Germans in a Nazi empire and to expand by acquiring “living space” (Lebensraum) in eastern Europe.

By 1933, Hitler’s foreign policy ideas were clear from his speeches and writings. However, in the first years of the Nazi regime, he tried to pose as a peaceful leader.

British Knowledge of Nazi Foreign Policy Ideas

In 1933, the British government was aware of Hitler’s ideas about foreign policy and war. In April of that year, the British Ambassador to Germany sent a dispatch back to London. The dispatch summarized Hitler’s political treatise and autobiography, Mein Kampf. This report made clear Hitler’s desire to use war and military might to redraw the map of Europe.

British officials were not sure whether to take Hitler’s manifesto seriously or how to respond to it. Some speculated that Hitler’s priorities would change as he took on the responsibilities of governing. Notably, Neville Chamberlain believed that the British government could negotiate with Hitler in good faith. Chamberlain hoped that by appeasing Hitler (i.e. agreeing to some of his demands), the Nazis would not resort to war.

Others warned that Hitler could not be trusted by the normal standards of international diplomacy. The most notable of these countervailing voices was Winston Churchill. Churchill was a prominent political voice and Member of Parliament in the 1930s. He repeatedly issued public warnings about the dangers Hitler and fascism posed to Britain.

Why did Britain choose appeasement in the early 1930s?

A variety of factors pushed the British government to pursue a policy of appeasement and to try to avoid war at all cost. Among the most important factors were domestic concerns, imperial politics, and other geopolitical considerations.

British Domestic Concerns

The British policy of appeasement was partly a reflection of domestic issues, including economic problems and antiwar sentiment. In the 1930s, the Great Depression, known in Britain as the Great Slump, caused unemployment to skyrocket. Economic distress led to rallies and demonstrations in the streets.

Antiwar sentiment and support for the policy of appeasement were widespread in Britain. The most powerful segments of British society supported appeasement. This included prominent business leaders and the royal family. The British Broadcasting Company (BBC) and The Times publicly endorsed the policy. Most Conservative Party leaders also supported it, with Winston Churchill being the notable exception.

British Imperial Politics

Britain’s imperial politics also shaped the British government’s attitudes towards war and appeasement. British wealth, power, and identity depended on the empire, which included dominions and colonies. During World War I, the British had relied on their empire for resources and troops. In the event of another world war, the British needed the empire to win. But, imperial support was less certain in the 1930s than it had been at the start of World War I.

In the 1930s, British politicians were concerned that a war would threaten the relationship between Britain and the dominions. The dominions included Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa. After World War I, these dominions had been granted a significant degree of independence within the British Empire. Politicians were not sure of universal dominion support in the event of another world war.

British politicians were also concerned that a war could provoke decolonization movements in what were then British colonies. Among the British colonies were Barbados, India, Jamaica, and Nigeria. From the perspective of the British, decolonization would be disastrous. It would lead to the loss of the colonies and their resources and raw materials. Furthermore, the British government feared that if they lost a war, they would lose their colonies in a postwar peace settlement.

Other Geopolitical Considerations

The British policy of appeasement was also a reaction to the diplomatic landscape of the 1930s. The strongest international players at the time (namely the United States, Italy, the Soviet Union, and France) each had their own domestic and geopolitical considerations. And, the League of Nations, which had been created to prevent war, proved to be ineffective in the face of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italian aggression.

The British Appeasement of the Nazis in the Face of German Rearmament, 1933–1937

From 1933 to 1937, the British government deployed the policy of appeasement in response to Nazi Germany’s rearmament. Beginning in the fall of 1933, the Nazis made a series of moves signaling that they did not intend to abide by existing treaties or accept the post-World War I world order. In 1933, Nazi Germany withdrew from an international disarmament conference and from the League of Nations. In 1935, the Nazi regime publicly announced the creation of a German air force (Luftwaffe) and the reinstatement of conscription. Then, in 1936, the Nazis remilitarized the Rhineland, a region in western Germany on the border with France.

Many members of the international community were alarmed by the Nazis’ actions and were concerned about Hitler’s future intentions. But there was no consensus about how best to respond to Hitler’s foreign policy.

The British governments under Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald (1929–1935) and Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin (1935–1937) chose not to sanction or punish Nazi Germany for violating international agreements. Rather, they sought to negotiate with the Germans. In June 1935, the British signed the Anglo-German Naval Agreement with Nazi Germany. The agreement allowed Germany to maintain a naval force much larger than what they were permitted to maintain under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. British leaders hoped that this agreement would prevent a naval arms race between Britain and Germany.

Neville Chamberlain and the Appeasement of Nazi Territorial Aggression, 1938

Neville Chamberlain became Prime Minister in May 1937. As Prime Minister, he hoped to focus on domestic rather than international concerns. But, Chamberlain could not avoid foreign policy for long.

Germany Annexes Austria

In March 1938, Nazi Germany annexed Austria, a blatant violation of post World War I peace treaties. The annexation of Austria signaled the Nazis’ complete disregard for their neighbor’s sovereignty and borders. Despite this, the international community accepted it as a done deal. No foreign government intervened. The international community hoped that German expansionism would stop there.

Some condemned the decision not to intervene in Austria. During a speech in the House of Commons in March 1938, Churchill warned that the annexation of Austria was just the Nazis’ first act of territorial aggression. He said,

The gravity of the [annexation of Austria] cannot be exaggerated. Europe is confronted with a programme of aggression, nicely calculated and timed, unfolding stage by stage, and there is only one choice open…either to submit, like Austria, or else to take effective measures…Resistance will be hard…yet I am persuaded [that the government will decide to act ]…to preserve the peace of Europe and, if it cannot be preserved, to preserve the freedom of the nations of Europe. If we were to delay, … [h]ow many friends would be alienated, how many potential allies should we see go down…?

In the months that followed, Churchill began to advocate for a military defense alliance among European nations. To many, Churchill’s opposition to appeasement and his repeated warnings about Hitler seemed hawkish and paranoid. His insistence that Britain must prepare for war did not endear him to his fellow members of the Conservative Party who supported Chamberlain.

The Sudetenland Crisis

All hopes that Germany would stop with Austria were dashed almost immediately. Hitler set his sights on the Sudetenland, a largely German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia. In summer 1938, the Nazis manufactured a crisis in the Sudetenland. They falsely claimed that Germans in the region were being oppressed by the Czechoslovak government. In reality, the Nazis wanted to annex the region and were seeking an excuse to occupy the Sudetenland. Hitler threatened war if the Czechoslovaks refused to cede the territory to Germany.

The British saw the German-Czechoslovak conflict as an international crisis. Austria had been diplomatically isolated at the time Nazi Germany annexed it. By contrast, Czechoslovakia had important alliances with France and the Soviet Union. Thus, the Sudetenland crisis had the potential to break out into a European or even world war.

Chamberlain Negotiates with Hitler

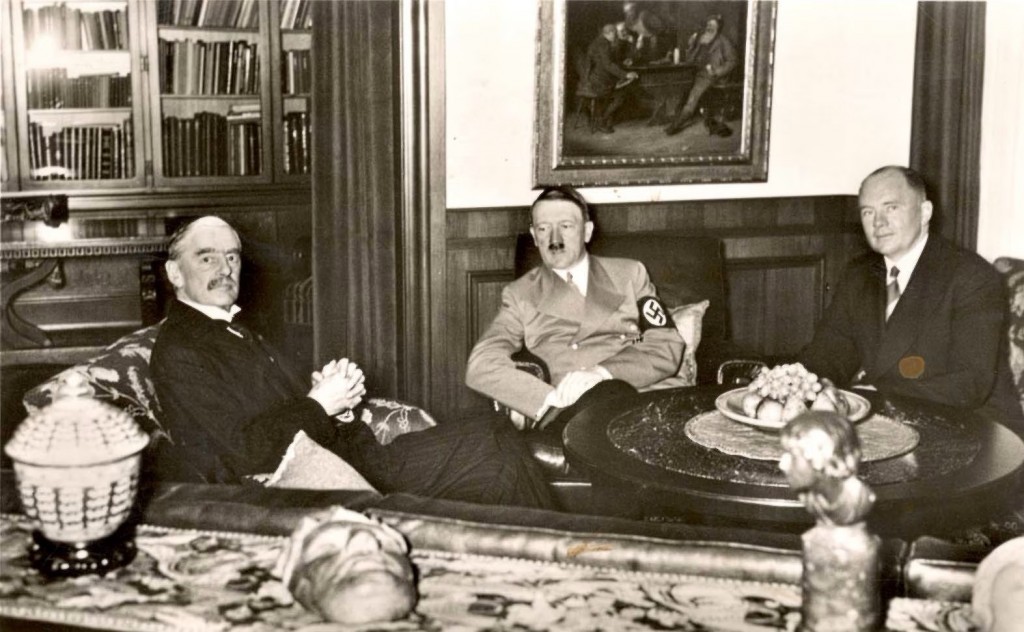

In September 1938, Europe seemed to be on the brink of war. It was at this point that Chamberlain personally got involved. On September 15, 1938, Chamberlain flew to Hitler’s vacation home in Berchtesgaden to negotiate the German leader’s terms. Chamberlain’s goal was to reach a diplomatic solution in order to avoid war.

But the matter remained unresolved. Thus, Chamberlain and Hitler met again on September 22 and 23. At the second meeting, Hitler told Chamberlain that Germany would occupy the Sudetenland by October 1, with or without an international agreement.

On September 27, Chamberlain gave a radio address explaining his stance regarding the negotiations and the fate of the Sudetenland:

“How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas-masks here because of a quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing… However much we may sympathize with a small nation confronted by a big and powerful neighbor, we cannot in all circumstances undertake to involve the whole British Empire in war simply on her account. If we have to fight it must be on larger issues than that.”

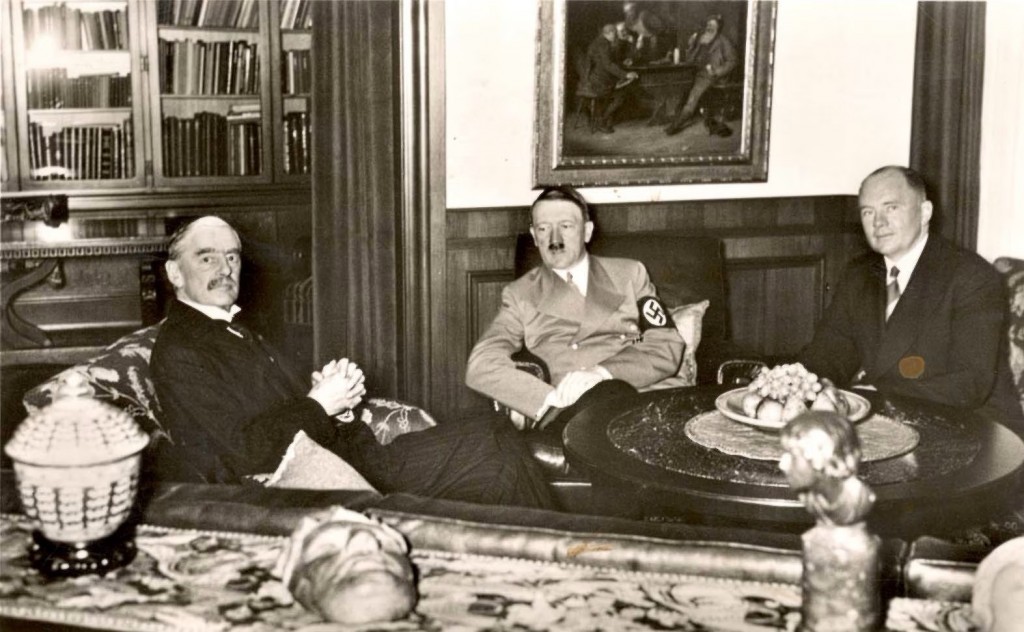

The Munich Agreement, September 29–30, 1938

On September 29–30, 1938, an international conference took place in Munich. The attendees were Chamberlain, Hitler, French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier, and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. The Czechoslovak government was not included in the negotiations. In Munich, Chamberlain and the others agreed to the cession of the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia to Germany, effective October 1. In exchange for the Sudeten concessions, Hitler renounced any claims to the rest of Czechoslovakia. War was averted for the time being. The British, French, and Italians blatantly disregarded Czechoslovakia’s sovereignty in the name of avoiding war.

The Munich Agreement was Britain’s most significant act of appeasement to date.

Neville Chamberlain: “Peace for Our Time”

Chamberlain returned from the meeting in Munich triumphant. In London, he famously proclaimed:

“My good friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honor. I believe it is peace for our time.”

Chamberlain is sometimes mistakenly quoted as having said “peace in our time.”

Winston Churchill Condemns the Munich Agreement

Chamberlain’s optimism did not go unchallenged. In a speech to the House of Commons on October 5, 1938, Winston Churchill condemned the Munich Agreement. He referred to it as a “total and unmitigated defeat” for Britain and the rest of Europe. Moreover, Churchill claimed that the British policy of appeasement had “deeply compromised, and perhaps fatally endangered, the safety and even the independence of Great Britain and France.”

The Failure of the Munich Agreement and the End of Appeasement

The Munich Agreement failed to stop Nazi Germany’s territorial aggression. In March 1939, Nazi Germany dismantled Czechoslovakia and occupied the Czech lands, including Prague. Based on Hitler’s rhetoric, it was clear that the Nazis’ next target was Poland, Germany’s neighbor to the east.

The Nazi invasion of the Czech lands changed British foreign policy. The British government slowly began to prepare for what now seemed to be an inevitable war. In May 1939, the British parliament passed the Military Training Act of 1939, a limited conscription.

Britain also reinforced its commitment to partners in Europe. Soon after Nazi Germany occupied Prague, the British and French governments officially guaranteed to help protect Poland’s sovereignty. In late August 1939, the British and Polish governments signed an agreement reinforcing this point. The British promised to come to Poland’s aid in the event of an attack by an aggressive foreign power. This agreement was signed just days before Nazi Germany invaded Poland.

Britain Declares War on Nazi Germany

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland. Despite the recently signed Anglo-Polish agreement, the British government first attempted a diplomatic approach in a final effort to avoid going to war. The Nazis ignored these diplomatic overtures.

On September 3, the British and French governments each declared war on Germany. These declarations turned the German invasion of Poland into a broader war—known as World War II. That same day, the British parliament passed a law introducing general conscription. Chamberlain spoke to the British people in a radio address:

You can imagine what a bitter blow it is to me that all my long struggle to win peace has failed. Yet I cannot believe that there is anything more or anything different that I could have done and that would have been more successful.

Up to the very last it would have been quite possible to have arranged a peaceful and honorable settlement between Germany and Poland. But Hitler would not have it. He had evidently made up his mind to attack Poland whatever happened....His action shows convincingly that there is no chance of expecting that this man will ever give up his practice of using force to gain his will. He can only be stopped by force.

The British government mobilized for war as quickly as possible, both at home and across the empire. It also established a naval blockade against Germany. Despite the fact that Germany and Britain were officially at war, there was only limited engagement between the two militaries. Consequently, this period was known as the “Phoney War” or the “Bore War.”

The Phoney War effectively ended in May 1940 when Germany invaded Belgium, France, and the Netherlands. The British had sent a military force known as the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to France in September 1939. In May 1940, the BEF fought against the Germans alongside the Belgian, French, and Dutch armies. Eventually, the BEF retreated to Dunkirk and were subsequently evacuated.

The rapid advance of German forces earned Neville Chamberlain much criticism. He found himself increasingly unable to form a national government. Following Britain's failure to save Norway from Germany occupation in April 1940, he lost crucial support and resigned as Prime Minister in May. He died just months later of cancer.

Upon Chamberlain’s resignation, Winston Churchill took over as Britain’s wartime prime minister. He steered Britain through the Battle of Britain, including the bombing of London known as the Blitz. He set British wartime policy and managed Britain’s wartime alliances with the United States and Soviet Union.

Over the next five years, the British fought against the Nazis and their allies in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. The Allied Powers (including the British) finally defeated Nazi Germany in May 1945.

Appeasement in Hindsight

The catastrophes of World War II and the Holocaust have shaped the world’s understanding of appeasement. The diplomatic strategy is often seen as both a practical and a moral failure.

Today, based on archival documents, we know that appeasing Hitler was almost certainly destined to fail. Hitler and the Nazis were intent upon waging an offensive war and conquering territory. But it is important to remember that those who condemn Chamberlain often speak with the benefit of hindsight. Chamberlain, who died in 1940, could not possibly have foreseen the scale of atrocities committed by the Nazis and others during World War II.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

The United States had adopted a foreign policy of isolationism. Fascist Italy was closely aligned with Nazi Germany. The Soviet Union was a Communist country. It existed in relative isolation from the rest of the international community, and had a tense relationship with Great Britain. Furthermore, the British feared the spread of Communism. France was interested in defending itself against a militarily strong Germany. However, the British disagreed with the French approach because the French wanted to take a hardline against Germany that the British feared would lead to war.