Timeline of the German Military and the Nazi Regime

This timeline chronicles the relationship between the professional military elite and the Nazi state. It pays specific attention to the military leaders’ acceptance of Nazi ideology and their role in perpetrating crimes against Jews, prisoners of war, and unarmed civilians in the name of that ideology.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, Germany’s military generals claimed they had fought honorably in World War II. They insisted it was the SS—the Nazi elite guard—and the SS leader, Heinrich Himmler, who were responsible for all crimes.

This myth of the German military’s “clean hands” was largely accepted in the United States, where American military leaders, embroiled in the Cold War, looked to their German counterparts for information that would help them against the Soviet Union. And because the few available Soviet accounts of the war were deemed untrustworthy—and most of the crimes committed by the German military had taken place in Soviet territory—the myth remained unchallenged for decades.

This led to two long-lasting distortions of the historical record of World War II. First, German generals came to be seen as models of military skill rather than as war criminals complicit in the crimes of the Nazi regime. Second, the German military’s role in the Holocaust was largely forgotten.

This timeline addresses these distortions by chronicling the relationship between the professional military elite and the Nazi state. It pays specific attention to the military leaders’ acceptance of Nazi ideology and their role in perpetrating crimes against Jews, prisoners of war, and unarmed civilians in the name of that ideology.

World War I (1914–1918)

World War I was one of the most destructive wars in modern history. Initial enthusiasm on all sides for a quick and decisive victory faded as the war devolved into a stalemate of costly battles and trench warfare, particularly on the western front. Over nine million soldiers died, a figure which far exceeded the military deaths in all the wars of the previous hundred years combined. Germany alone lost approximately two million soldiers. The enormous losses on all sides resulted in part from the introduction of new weapons, like the machine gun and gas warfare, as well as from the failure of military leaders to adjust their tactics to the increasingly mechanized nature of warfare.

The Great War was a defining experience for the German military. Perceived failures on the battlefield and the homefront shaped its beliefs about war and informed its interpretation of the relationship between civilians and soldiers.

October 1916: The German Military’s Jewish Census

During World War I, antisemitism in Germany increased. The Jewish population was approximately 600,000, less than one percent of the German population. Antisemitic newspapers and politicians attacked Jews, falsely claiming that German Jews were cowards who were shirking their duty by staying away from combat. The Prussian Minister of War ordered a “Judenzählung” (literally, “census of Jews” or “Jewish census”). The German Jewish community was outraged by the census, which was carried out throughout the military in the midst of the war. For reasons that are not entirely clear, the results were never published. Debate continued even after the war, with antisemitic groups and Jewish groups publishing competing statistics. The Jewish community calculated that about 100,000 Jews had served in the German military and 12,000 lost their lives in battle.

November 11, 1918: The Armistice and the Stab-in-the-Back Legend

After more than four years of fighting, an armistice, or ceasefire, between defeated Germany and the Entente powers went into effect on November 11, 1918. For the German people, the defeat was an enormous shock; they had been told that victory was inevitable.

One way some Germans made sense of their sudden defeat was through the “stab-in-the-back” legend. The legend claimed that internal “enemies”—primarily Jews and Communists—had sabotaged the German war effort. In truth, German military leaders convinced the German emperor to seek peace because they knew that Germany could not win the war, and they feared the country’s imminent collapse. Many of these same military leaders then spread the stab-in-the-back legend to deflect blame for the defeat away from Germany’s military leaders.

June 28, 1919: The Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919. Germany’s newly formed democratic government saw the treaty as a “dictated peace” with harsh terms.

In addition to other provisions, the treaty limited German military power. It restricted the German army to a 100,000-man volunteer force, with a maximum of 4,000 officers, who were each required to serve for 25 years. This was intended to prevent the German army from using rapid turnover to train more officers. The treaty forbade production of tanks, poisonous gas, armored cars, airplanes, and submarines and the import of weapons. It dissolved the elite planning section of the German army, known as the General Staff, and closed the military academies and other training institutions. The treaty demanded the demilitarization of the Rhineland, forbidding German military forces from being stationed along the border with France. These changes greatly limited the career prospects of German military officers.

January 1, 1921: The German Military is Reestablished

The new German republic, known as the Weimar Republic, faced many difficult tasks. One of the most challenging was the reorganization of the military, called the Reichswehr. The government reinstituted the Reichswehr on January 1, 1921, under the leadership of General Hans von Seeckt. The Reichswehr’s small and homogenous officer corps was characterized by antidemocratic attitudes, opposition to the Weimar Republic, and attempts to undermine and circumvent the Treaty of Versailles.

Throughout the 1920s, the military repeatedly violated the treaty. For example, the disbanded General Staff simply transferred its planning to the newly established “Troop Office.” The military also secretly imported weapons that had been banned by the Treaty of Versailles. It even signed an agreement with the Soviet Union, which allowed it to conduct prohibited tank exercises in Soviet territory. The Reichswehr’s mid-level officers later became the leaders of the German military under Hitler.

July 27, 1929: The Geneva Convention

On July 27, 1929, Germany and other leading countries signed the Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War in Geneva. This international agreement built on the earlier Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 to increase protections for prisoners of war. The convention was one of several important international agreements regulating war in the 1920s. The Geneva Protocol (1925) updated restrictions relating to the use of poison gas. In 1928, the Kellogg-Briand Pact renounced war as a national policy.

These postwar agreements were an attempt to update international law in a way that would prevent another conflict as destructive as World War I. However, the dominant attitude within the German army was that military necessity always outweighed international law.

February 3, 1933: Hitler Meets with Top Military Leaders

Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Just four days later, he met privately with top military leaders to attempt to win their support. This was especially important because the military had historically played a very important role in German society and therefore had the ability to overthrow the new regime.

The military leadership did not fully trust or support Hitler because of his populism and radicalism. However, the Nazi Party and the German military had similar foreign policy goals. Both wanted to renounce the Treaty of Versailles, to expand the German armed forces, and to destroy the Communist threat. In this first meeting, Hitler tried to reassure the German officer corps. He talked openly about his plans to establish a dictatorship, reclaim lost land, and wage war. Almost two months later, Hitler showed his respect for the German military tradition by publicly bowing to President Hindenburg, a celebrated World War I general. In October 1933 Germany withdrew from both the World Disarmament Conference and the League of Nations.

February 28, 1934: The “Aryan Paragraph”

Passed on April 7, 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service included the Aryan Paragraph. The paragraph called for all Germans of “non-Aryan” descent (i.e., Jews) to be forcibly retired from the civil service.

The Aryan Paragraph did not initially apply to the armed forces. On February 28, 1934, however, Defense Minister Werner von Blomberg voluntarily put it in effect for the military as well. Because the Reichswehr already discriminated against Jews and blocked their promotion, the policy affected fewer than 100 soldiers. In a memorandum to high-level military leaders, Colonel Erich von Manstein condemned the firings on the basis of the traditional values of the German military and its professional code, to little effect. Blomberg’s decision to apply the Aryan Paragraph was one of many ways that senior military officials worked with the Nazi regime. They also added Nazi symbols to military uniforms and insignia and introduced political education based on Nazi ideals into military training.

June 30–July 2, 1934: The “Night of the Long Knives”

In 1933–1934, Hitler put an end to efforts by SA leader Ernst Röhm to replace the professional army with a people’s militia centered on the SA. Military leaders demanded that Röhm be stopped. Hitler decided that a professionally trained and organized military better suited his expansionist aims. He intervened on the military’s behalf in exchange for their future support.

Between June 30 and July 2, 1934, the Nazi Party leadership murdered the leadership of the SA, including Röhm, and other opponents. The murders confirmed an agreement between the Nazi regime and the military that would remain intact, with rare exceptions, until the end of World War II. As part of this agreement, military leaders supported Hitler when he proclaimed himself Führer (leader) of the German Reich in August 1934. The military leaders immediately wrote a new oath that swore their service to Hitler personally as the personification of the German Nation.

March 1935–March 1936: Creating the Wehrmacht

In early 1935, Germany took its first public steps to rearm, in violation of the Treaty of Versailles. On March 16, 1935, a new law reintroduced the draft and officially expanded the German army to 550,000 men.

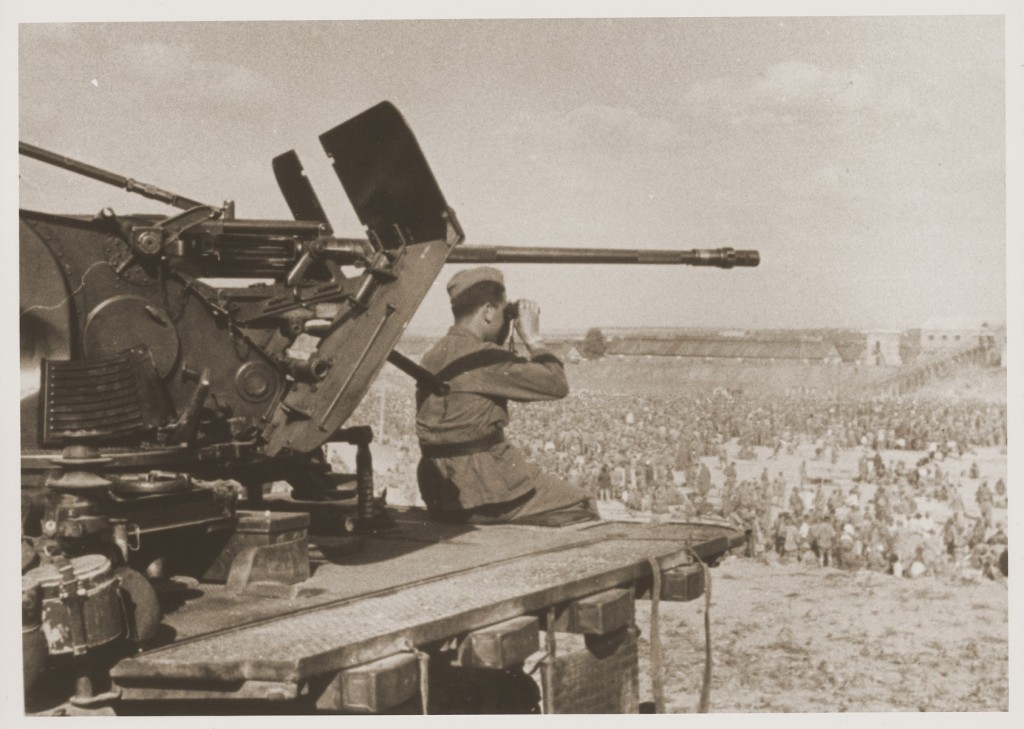

In May, a secret Reich Defense Law transformed the Reichswehr into the Wehrmacht and made Hitler its commander in chief, with a “Minister of War and Commander of the Wehrmacht” under him. The name change was largely cosmetic, but the intent was to create a force capable of a war of aggression, rather than the defensive force created by the treaty. In addition, the conscription law excluded Jews, much to the disappointment of those Jewish men who wanted to prove their continuing loyalty to Germany. Military leaders worked with the Nazi regime to expand arms production. In March 1936, the new Wehrmacht remilitarized the Rhineland.

November 5, 1937: Hitler Meets with Top Military Leaders Again

On November 5, 1937, Hitler held a small meeting with the foreign minister, the war minister, and the heads of the army, navy, and air force. Hitler discussed his vision for Germany’s foreign policy with them, including plans to absorb Austria and Czechoslovakia soon, by force if necessary, with further expansion to follow. The Commander in Chief of the Army Werner Freiherr von Fritsch, Minister of War von Blomberg, and Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath objected, not on moral grounds, but because they believed Germany was not ready militarily, especially if Britain and France joined the war. In the days and weeks that followed, several other military leaders who learned of the meeting also expressed their disapproval.

January–February 1938: The Blomberg-Fritsch Affair

In early 1938, two scandals involving top Wehrmacht leaders allowed the Nazis to remove commanders who did not fully support Hitler’s plans (as laid out in the November meeting). First, Minister of War Blomberg had recently married, and information came to light that his wife had “a past,” involving, at the least, pornographic pictures. This was completely unacceptable for any army officer. Hitler (with the full support of the other senior generals) demanded Blomberg’s resignation. Around the same time, Commander in Chief of the Army von Fritsch resigned after Himmler and Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring trumped up false charges of homosexuality against him.

The two resignations became known as the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair. They gave Hitler the opportunity to restructure the Wehrmacht under his control. The position of Minister of War was taken over by Hitler himself, and General Wilhelm Keitel was appointed as the military head of the armed forces. Fritsch was replaced with the much more pliable Colonel-General Walther von Brauchitsch. These changes were just the most public. Hitler also announced a series of forced resignations and transfers at a cabinet meeting in early February.

March 1938–March 1939: Foreign Policy and Expansion

From March 1938 to March 1939, Germany made a series of territorial moves that risked a European war. First, in March 1938, Germany annexed Austria. Hitler then threatened war unless the Sudetenland, a border area of Czechoslovakia containing an ethnic German majority, was surrendered to Germany. The leaders of Britain, France, Italy, and Germany held a conference in Munich, Germany, on September 29–30, 1938. They agreed to the German annexation of the Sudetenland in exchange for a pledge of peace from Hitler. On March 15, 1939, Hitler violated the Munich Agreement and moved against the rest of the Czechoslovak state. These events sparked tension within the military’s High Command. General Ludwig Beck, Chief of the General Staff, had long protested the prospect of another unwinnable war. However, his colleagues refused to back him up—they were willing to hand over the reins of strategy to the Führer. Beck resigned, to no effect.

September 1, 1939: Germany Invades Poland

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded and quickly defeated Poland, beginning World War II. The German occupation of Poland was exceptionally brutal. In a campaign of terror, German police and SS units shot thousands of Polish civilians and required all Polish males to perform forced labor. The Nazis sought to destroy Polish culture by eliminating the Polish political, religious, and intellectual leadership. These crimes were perpetrated mainly by the SS, although Wehrmacht leaders were in full support of the policies. Many German soldiers also participated in the violence and looting. Some in the Wehrmacht were unhappy with the involvement of their soldiers, shocked by the violence, and concerned about the lack of order among the soldiers. Generals Blaskowitz and Ulex even complained to their superiors about the violence. However, they were quickly silenced.

April 7–June 22, 1940: The Invasion of Western Europe

In the spring of 1940, Germany invaded, defeated, and occupied Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and France. This string of victories—especially the astoundingly quick defeat of France—greatly increased Hitler’s popularity at home and within the military. The few military officers who had objected to his plans now found their credibility destroyed and the potential to organize opposition to the regime reduced. After the victory in western Europe, Hitler and the Wehrmacht turned their attention to planning an invasion of the Soviet Union.

March 30, 1941: Planning the Invasion of the Soviet Union

On March 30, 1941, Hitler spoke secretly to 250 of his principal commanders and staff officers on the nature of the upcoming war against the Soviet Union. His speech emphasized that the war in the east would be conducted with extreme brutality with the aim of destroying the Communist threat. Hitler’s audience knew he was calling for clear violations of the laws of war, but there were no serious objections. Instead, following Hitler’s ideological position, the military issued a series of orders that made it clear they intended to wage a war of annihilation against the Communist state. The most notorious of these orders include the Commissar Order and the Barbarossa Jurisdiction Decree. Together these and other orders established a clear working relationship between the Wehrmacht and the SS. In addition, the orders clarified that soldiers would not be punished for committing acts contrary to the internationally agreed upon rules of war.

April 6, 1941: The Invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece

The Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941, dismembering the country and exploiting ethnic tensions. In one region, Serbia, Germany established a military occupation administration that exercised extreme brutality against the local population. During the summer of that year, German military and police authorities interned most Jews and Roma (Gypsies) in detention camps. By the fall, a Serbian uprising had inflicted serious casualties upon German military and police personnel. In response, Hitler ordered German authorities to shoot 100 hostages for every German death. German military and police units used this order as a pretext to shoot virtually all male Serbian Jews (approximately 8,000 men); approximately 2,000 actual and perceived Communists, Serb nationalists, and democratic politicians of the interwar era; and approximately 1,000 Romani men.

June 22, 1941: The Invasion of the Soviet Union

German forces invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Three army groups, consisting of more than three million German soldiers, attacked the Soviet Union across a broad front, from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south.

In accordance with their orders, German forces treated the population of the Soviet Union with extreme brutality. They burned entire villages and shot the rural population of whole districts in retaliation for partisan attacks. They sent millions of Soviet civilians to perform forced labor in Germany and the occupied territories. German planners called for the ruthless exploitation of Soviet resources, especially of agricultural produce. This was one of Germany’s major war aims in the east.

June 1941–January 1942: The Systematic Killing of the Soviet POWs

From the beginning of the eastern campaign, Nazi ideology drove German policy towards Soviet prisoners of war (POWs). German authorities viewed Soviet POWs as inferiors and as part of the “Bolshevik menace.” They argued that because the Soviet Union was not a signatory to the 1929 Geneva Convention, its regulations requiring that POWs be given food, shelter, and medical care, and forbidding war work or corporal punishment, did not apply. This policy proved catastrophic for the millions of Soviet soldiers taken prisoner during the war.

By war’s end, over 3 million Soviet prisoners (about 58 percent) died in German captivity (versus about 3 percent of British or American prisoners). This death toll was neither an accident nor an automatic result of the war, but rather deliberate policy. The army and the SS cooperated in the shooting of hundreds of thousands of Soviet POWs, because they were Jews, or Communists, or looked “asiatic.” The rest were subjected to long marches, systematic starvation, no medical care, little or no shelter, and forced labor. Time and again German forces were called upon to take “energetic and ruthless action” and “use their arms” unhesitatingly “to wipe out any trace of resistance” from Soviet POWs.

Summer–Fall 1941: Wehrmacht Participation in the Holocaust

Most German generals did not see themselves as Nazis. However, they shared many of the Nazis’ goals. In their opinion, there were good military reasons to support Nazi policies. In the eyes of the generals, communism fed resistance. They also believed the Jews were the driving force behind communism.

When the SS offered to secure the rear areas and eliminate the Jewish threat, the army cooperated by providing logistical support to the units and coordinating their movements. Army units helped round up Jews for the shooting squads, cordoned off the killing sites, and sometimes took part in shootings themselves. They established ghettos for those whom the shooters left behind and relied on Jewish forced labor. When some troops showed signs of unease, the generals issued orders, justifying the killings and other harsh measures.

February 2, 1943: German 6th Army Surrenders at Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad, which lasted from October 1942 to February 1943, was a major turning point in the war. After months of fierce fighting and heavy casualties, and contrary to Hitler’s direct order, the surviving German forces (about 91,000 men) surrendered on February 2, 1943. Two weeks later, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels gave a speech in Berlin calling for radicalization of mobilization measures and total war. The speech acknowledged the difficulties the country was facing and marked the beginning of increased desperation on the part of the Nazi leadership.

Their defeat at Stalingrad forced German troops on the defensive and was the beginning of their long retreat back to Germany. This retreat was marked by widespread destruction as the military implemented a scorched earth policy on Hitler’s orders. There was also an increased emphasis on maintaining military discipline, including ruthless arrests of soldiers who expressed doubts about Germany’s final victory.

July 20, 1944: Operation Valkyrie

Although generally unconcerned about Nazi crimes—several of the conspirators had even taken part in the killing of Jews—a small group of senior military officers decided that Hitler had to die. They blamed Hitler for losing the war and felt that his continued leadership posed a serious threat to Germany’s future. They attempted to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944, exploding a small but powerful bomb during a military briefing in his East Prussian headquarters at Rastenburg.

Hitler survived and the plot fell apart. He quickly took his revenge for this attempt on his life. Several generals were forced to take their own lives or face humiliating prosecution. Others were tried before the infamous People’s Court in Berlin and executed. While Hitler remained suspicious of the remaining members of the German officer corps, most continued to fight for him and for Germany until the country’s surrender in 1945.

1945–1948: Major War Crimes Trials

After the German surrender in May 1945, some military leaders were tried for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The highest ranking generals were included in the trial of 22 major war criminals before the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg, Germany, beginning in October 1945. Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl, both of the German Armed Forces High Command, were found guilty and executed. Both sought to blame Hitler. However, the IMT explicitly rejected the use of the superior orders as a defense.

Three subsequent IMT trials before an American military tribunal at Nuremberg also focused on the crimes of the German military. Many of those convicted were released early, under the pressure of the Cold War and the establishment of the Bundeswehr. Unfortunately, most perpetrators of crimes against humanity have never been tried or punished.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

FL Carsten, Reichswehr Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 50.

-

Footnote reference2.

Robert B. Kane, Disobedience and Conspiracy in the German Army, 1918-1945 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 82-83.

-

Footnote reference3.

Grundzüge deutscher Militärgeschichte, (Freiburg i.B.: Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt, 1993), 329.

-

Footnote reference4.

German Historical Institute, "Summary of Hitler's Meeting with the Heads of the Armed Services on November 5, 1937," Accessed November 25, 2019, http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=1540. An electronic translation of the original German meeting minutes, "Minutes of the Conference in the Reich Chancellery, Berlin, November 5, 1937, from 4:15–8:30PM," is available through the site, as originally translated from German and published by the United States Department of State.

-

Footnote reference5.

The Wannsee Conference and the Genocide of the European Jews: Catalogue with Selected Documents and Photos of the Permanent Exhibit. (Berlin: House of the Wannsee Conference, Memorial and Education Site, 2007), 39-40.

Critical Thinking Questions

How did German professionals and civil leaders contribute to the persecution of Jews and other groups?

What was the relationship between the progress of the war and the mass murder of Europe’s Jews?