Eugenics

Theories of eugenics, or “racial hygiene” in the German context, shaped many of Nazi Germany’s persecutory policies.

Key Facts

-

1

Eugenics, or “racial hygiene,” was a scientific movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

-

2

While today eugenics may be regarded as a pseudoscience, it was seen as cutting edge science in the early decades of the twentieth century. Eugenics societies sprang up throughout most of the industrialized world, particularly in the United States, Great Britain, and Germany.

-

3

Eugenics provided the basis for the Nazi compulsory sterilization policy and underpinned the murder of the institutionalized disabled in the clandestine “euthanasia” (T4) program.

Background

A significant number of Nazi persecutory policies stemmed from theories of racial hygiene, or eugenics. Such theories were prevalent among the international scientific community in the first decades of the twentieth century. The term “eugenics” (from the Greek for “good birth or stock”) was coined in 1883 by the English naturalist Sir Francis Galton. The term's German counterpart, “racial hygiene” (Rassenhygiene), was first employed by German economist Alfred Ploetz in 1895. At the core of the movement’s belief system was the principle that human heredity was fixed and immutable.

Eugenic Theories

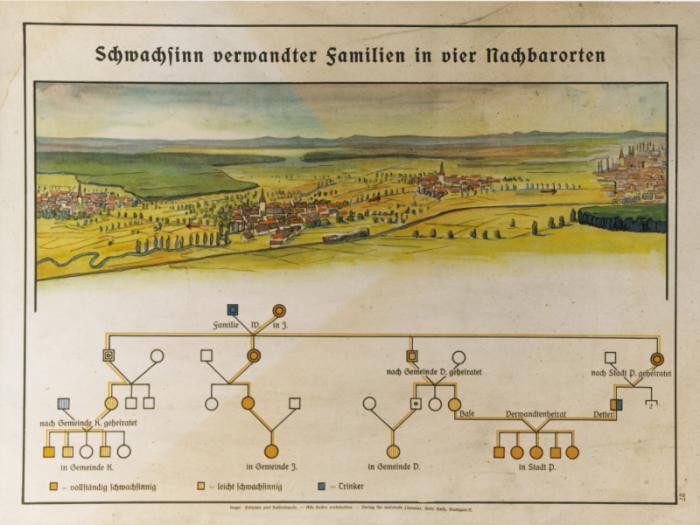

For eugenicists, the social ills of modern society—criminality, mental illness, alcoholism, and even poverty—stemmed from hereditary factors. Supporters of eugenic theory did not believe that these problems resulted from environmental factors, such as the rapid industrialization and urbanization of the late 19th century in Europe and North America. Rather, they advanced the science of eugenics to address what they regarded as a decline in public health and morality.

Eugenicists had three primary objectives. First, they sought to discover “hereditary” traits that contributed to societal ills. Second, they aimed to develop biological solutions to these problems. Finally, eugenicists sought to campaign for public health measures to combat them.

The International Impact of Eugenic Theories

Eugenics found its most radical interpretation in Germany, but its influence was by no means limited to that nation alone. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, eugenic societies sprang up throughout most of the industrialized world. In Western Europe and the United States, the movement was embraced in the 1910s and 1920s. Most supporters in those places endorsed the objectives of American advocate Charles Davenport. Davenport advocated for the development of eugenics as “a science devoted to the improvement of the human race through better breeding.” Its supporters lobbied for “positive” eugenic efforts. They advocated for public policies that aimed to maintain physically, racially, and hereditarily “healthy” individuals. For example, they sought to provide marital counseling, motherhood training, and social welfare to “deserving” families. In doing so, eugenics supporters hoped to encourage “better” families to reproduce.

Efforts to support the “productive” members of society brought negative measures. For instance, there were efforts to redirect economic resources from the “less valuable” in order to provide for the “worthy.” Eugenicists also targeted the mentally ill and cognitively impaired. Many members of the eugenics community in Germany and the United States promoted strategies to marginalize segments of society with limited mental or social capacity. They promoted limiting their reproduction through voluntary or compulsory sterilization. Eugenicists argued that there was a direct link between diminished capacity and depravity, promiscuity, and criminality.

Members of the eugenic community in Germany and the US also viewed the racially “inferior” and poor as dangerous. Eugenicists maintained that such groups were tainted by deficiencies they inherited. They believed that these groups endangered the national community and financially burdened society.

More often than not eugenicists’ “scientifically-drawn” conclusions did little more than to incorporate popular prejudice. However, by employing “research” and “theory” to their efforts, eugenicists could assert their beliefs as scientific fact.

Nazi Racial Hygiene

German eugenics pursued a separate and terrible course after 1933. Before 1914, the German racial hygiene movement did not differ greatly from its British and American counterparts. The German eugenics community became more radical shortly after World War I. The war brought unprecedented carnage. In addition, Germany saw economic devastation in the years between World War I and World War II. These factors heightened the division between those considered hereditarily “valuable” and those considered “unproductive.” For instance, some believed that hereditarily “valuable” Germans had died on the battlefield, while the “unproductive” Germans institutionalized in prisons, hospitals, and welfare facilities remained behind. Such arguments resurfaced in the Weimar and early Nazi eras as a way to justify eugenic sterilization and a decrease in social services for the disabled and institutionalized.

By 1933, the theories of racial hygiene were embedded into the professional and public mindset. These theories influenced the thinking of Adolf Hitler and many of his followers. They embraced an ideology that blended racial antisemitism with eugenic theory. In doing so, the Hitler regime provided context and latitude for the implementation of eugenic measures in their most concrete and radical forms.

Racial hygiene shaped many of Nazi Germany’s racial policies. Medical professionals implemented many of these policies and targeted individuals the Nazis defined as “hereditarily ill”: those with mental, physical, or social disabilities. Nazis claimed these individuals placed both a genetic and a financial burden upon society and the state.

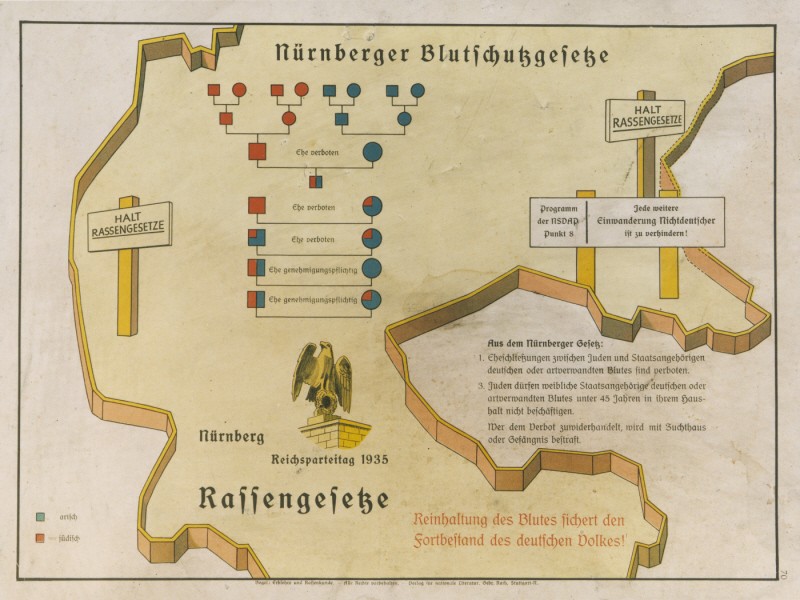

Nazi authorities resolved to intervene in the reproductive capacities of persons classified as “hereditarily ill.” One of the first eugenic measures they initiated was the 1933 Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases (“Hereditary Health Law”). The law mandated forcible sterilization for nine disabilities and disorders, including schizophrenia and “hereditary feeblemindedness.” As a result of the law, 400,000 Germans were ultimately sterilized in Nazi Germany. In addition, eugenic beliefs shaped Germany’s 1935 Marital Hygiene Law. This law prohibited the marriage of persons with “diseased, inferior, or dangerous genetic material” to “healthy” German “Aryans.”

Conclusion

Eugenic theory provided the basis for the “euthanasia” (T4) program. This clandestine program targeted disabled patients living in institutions throughout the German Reich for killing. An estimated 250,000 patients, the overwhelming majority of them German “Aryans,” fell victim to this clandestine killing operation.