How Were the Crimes Defined?

After World War II, the victorious Allies took the unprecedented step of creating an International Military Tribunal (IMT) to hold German leaders individually accountable for violations of international law. The Nuremberg tribunal laid the foundation for a new system of international criminal law and accountability that continues developing today.

Key Facts

-

1

In August 1945, the four major Allied powers signed the Nuremberg Charter (also known as the London Agreement and Charter). The Charter created an International Military Tribunal (IMT) to try German leaders responsible for World War II and for mass crimes.

-

2

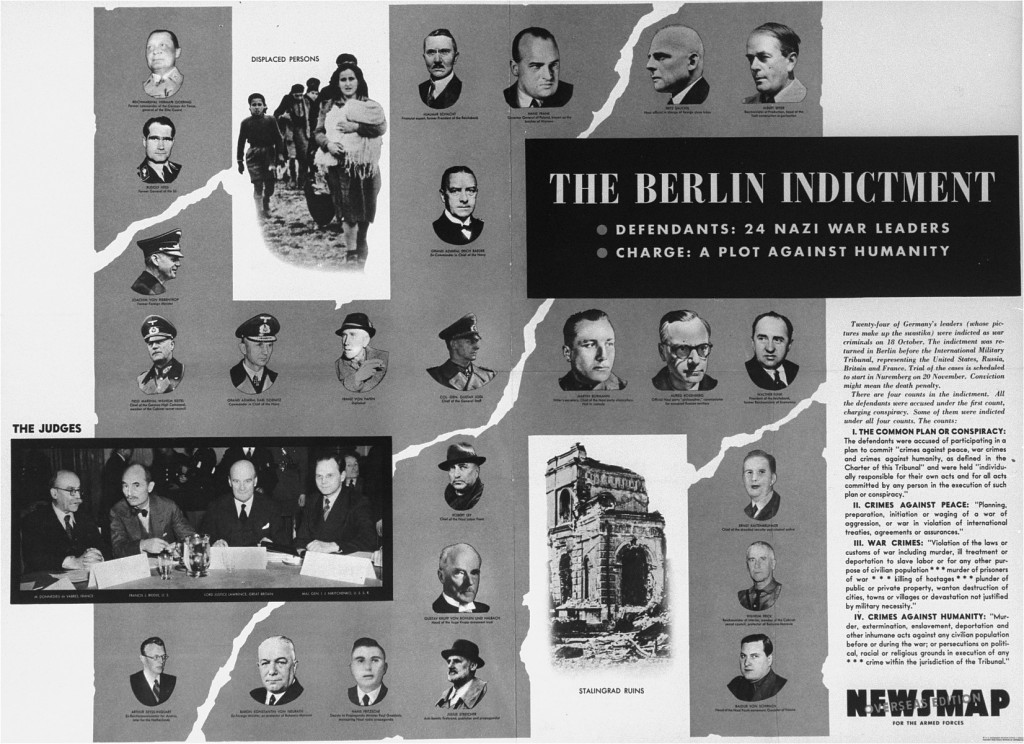

The Nuremberg Charter charged the IMT to conduct fair trials of the defendants for three specific crimes: war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity.

-

3

In 1946, the United Nations adopted the provisions of the Nuremberg Charter and the IMT judgment as binding international law. The principles and precedents established by the Charter and the IMT laid the foundation for international criminal law as it is practiced today.

Never before in legal history has an effort been made to bring within the scope of a single litigation the developments of a decade, covering a whole continent, and involving a score of nations, countless individuals, and innumerable events.

—US Chief Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson

Opening statement before the International Military Tribunal

Listen to an excerpt

Introduction

Today, there is a body of international criminal law that is used to prosecute the perpetrators of mass atrocities. International and national courts have tried such crimes as genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity committed in a number of countries. These countries include the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Cambodia. This body of international criminal law rests upon precedents established by the International Military Tribunal (IMT) at Nuremberg.

The Nuremberg Charter

Even before the end of World War II, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin announced in the Moscow Declaration that perpetrators of atrocities, such as mass murder of Jews, would be tried by the nations where the crimes were committed. The three leaders promised that major war criminals whose crimes could not be tied to a particular geographic location would be punished by joint decision of the Allied governments. How the Allies would punish the major war criminals was not specified. At times, Churchill and Stalin favored simply executing them.

After the war ended in May 1945, the US government proposed trying the major war criminals in a special court of law. On August 8, 1945, representatives of the United States, France, Great Britain and the Soviet Union signed the London Agreement and Charter, also referred to as the Nuremberg Charter. The agreement established the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg, Germany, to try German leaders responsible for World War II and for mass crimes. The Charter set out the rules and functions of the IMT and defined the crimes that it would try.

Provisions of the Charter

The Nuremberg Charter provided that each of the major Allied powers—France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States—would assign one judge and one alternate judge to the IMT. All decisions required a majority vote by the four judges who heard the case.

The Charter instructed the IMT to conduct a fair trial and to grant defendants certain due process rights. Among these rights were the right to be represented in court by legal counsel, to cross-examine witnesses, and to present evidence and witnesses in their defense.

However, the Charter also specified that the defendants could not escape responsibility for their crimes by claiming that they had been following orders. Defendants were also not allowed to claim that they could not be prosecuted under international law for actions they took as officials of a sovereign power.

Defining the Crimes

The Nuremberg Charter (London Agreement and Charter) gave the IMT authority "to try and punish persons who, acting in the interest of the European Axis countries, whether as individuals or as members of organizations," committed any of the following crimes:

Crimes against peace—which included planning, preparing, initiating and waging a war of aggression, as well as conspiring to commit any of those acts;

War crimes—"violations of the laws or customs of war," including murder, ill-treatment, and deportation to slave labor of civilians, murder and ill-treatment of prisoners of war, and killing of hostages, as well as plunder and wanton destruction;

Crimes against humanity—defined as murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, or inhumane treatment of civilians, and persecution on political, racial or religious grounds.

While the charge of war crimes was based on existing international custom and conventions, crimes against peace and crimes against humanity had never been defined as punishable offenses under international law. The drafters of the Charter argued that both of the new charges were based on pre-World War II international conventions and declarations that condemned wars of aggression and violations of the laws of humanity.

The Charter also authorized the IMT to determine whether a defendant who committed crimes acted as a member of an organization, in which case the IMT could declare that organization a criminal organization.

The Charges and Findings of the IMT

The trial of 22 German leaders before the IMT in Nuremberg began on November 20, 1945, and ended on October 1, 1946. The IMT tried the defendants not only for the three crimes specified in its Charter but also on a fourth charge of conspiracy to commit any of those three crimes. In addition, it considered whether certain organizations of the Nazi Party or the German state or military were criminal organizations.

The IMT acquitted 3 defendants and convicted the other 19. Of those 19, 12 were sentenced to death.

The IMT also found the following organizations to be criminal organizations: the Leadership Corps of the Nazi Party; the Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei or Secret State Police); the SD (Sicherheitsdienst or Security Service of the Reichsfȕhrer SS), and the SS.

The IMT limited the definition of crimes against humanity to acts committed during war. This meant that the court did not consider crimes against humanity committed before the war.

The Nuremberg Principles

Two months after the IMT verdict, the United Nations General Assembly unanimously recognized the judgment and the Nuremberg Charter as binding international law. Based upon the judgment and the Charter, the UN’s International Law Commission defined a set of principles to guide the development and enforcement of international criminal law.

The key "Nuremberg principles" are:

- Crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity are offenses under international law;

- Any individual, even a government leader, who commits an international crime may be held legally accountable;

- Punishment for international crimes should be determined through a fair trial based upon the facts and the law;

- A perpetrator of an international crime who acted in obedience to orders from a superior still bears legal responsibility for the crime.

International criminal law has expanded considerably since the IMT reached its verdict. In 1948, for example, the UN recognized genocide as an international crime by approving the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Additional offenses, such as torture and sexual violence, have been added to the list of acts that qualify as war crimes and crimes against humanity. While the body of international criminal law has grown, its enforcement continues to rely upon the precedents and principles established by the Nuremberg Charter and the IMT.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

In justice to the men and to the nations associated in this prosecution, I must remind you of certain difficulties which may leave their mark on this case. Never before in legal history has an effort been made to bring within the scope of a single litigation the developments of a decade, covering a whole continent, and involving a score of nations, countless individuals, and innumerable events. Despite the magnitude of the task, the world has demanded immediate action. This demand has had to be met, though perhaps at the cost of finished craftsmanship. In my country, established courts, following familiar procedures, applying well-thumbed precedents, and dealing with the consequences of local and limited events, seldom commence a trial within a year of the event in litigation. Yet less than eight months ago today the courtroom in which you sit was an enemy fortress in the hands of the SS troops. Less than eight months ago nearly all of our witnesses and documents were in enemy hands. The law had not been codified, no procedures had been established, no tribunal was in existence, no usable courthouse stood here, none of the hundreds of tons of official German documents had been examined, no prosecuting staff had been assembled, nearly all of the present defendants were at large, and the four prosecuting powers had not yet joined in common cause to try them. I should be the last to deny that this court, this case, may very well suffer from incomplete researches and quite likely will not be the example of professional work which any of the prosecuting nations would normally wish to sponsor. It is, however, a completely adequate case to the judgment we shall ask you to render, and its fuller development we shall be obliged to leave to historians.

Critical Thinking Questions

Beyond the verdicts, what impact can trials have?

How were various professions involved in implementing Nazi policies and ideology? What lessons can be considered for contemporary professionals?

How have some professional codes of conduct changed following the Holocaust?