The Role of Civil Servants

Persecution of Jews and other groups was not solely the result of measures originating with Hitler and other Nazi zealots. Nazi leaders required the active help or cooperation of professionals working in diverse fields who in many instances were not convinced Nazis. Civil servants, from government officials to judges, helped draft, implement, and enforce laws aimed at depriving Jews of their rights, livelihoods, and assets.

When the Nazis assumed power in 1933, most German civil servants were conservative, nationalistic, and authoritarian in outlook. After political opponents were purged from the civil service, government workers shared the Nazis’ anti-communism and rejection of the Weimar Republic. They regarded the Nazi regime as legitimate and felt bound to “obey the law.” Most were not radically antisemitic, but did believe that Jews were “different” or had “too much influence.”

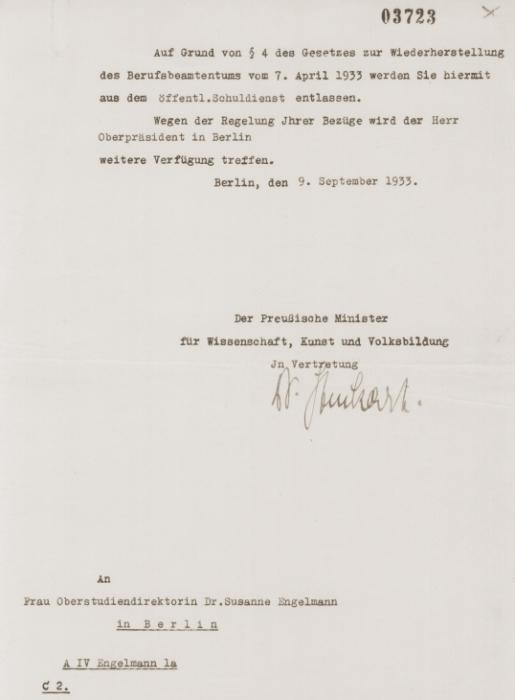

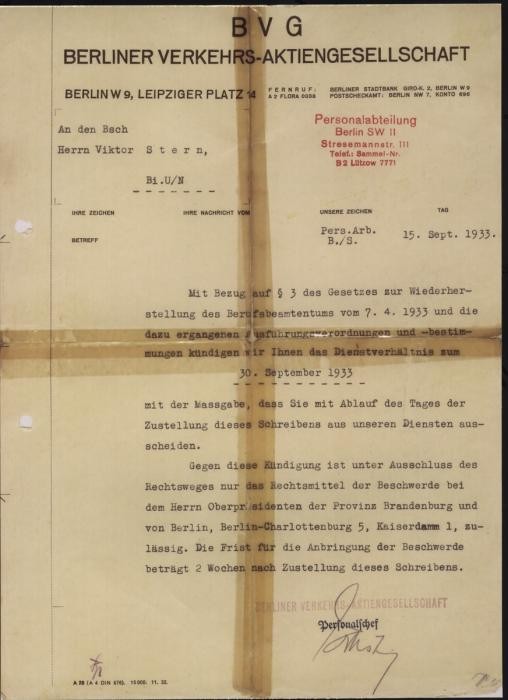

Helping to implement Nazi policies, civil servants working in various agencies, and as part of their normal work, drafted countless laws and decrees that, step by step, took away the full civil rights that German Jews had enjoyed as equal citizens before 1933. These included measures, for example, that defined the term “Jew,” prohibited marriages between “Jews” and “German-blooded” people, required the dismissal of Jews from civil service positions and other employment, imposed discriminatory taxes on “Jewish wealth,” blocked bank funds, and authorized the state to confiscate the property of deported Jews.

Civil servants also drew up the law mandating the sterilization of persons diagnosed with hereditary mental illnesses and mental and physical disabilities. Furthermore, they revised Paragraph 175, a German statute that criminalized sexual acts between men. The revision made the statute more vague and allowed Nazi jurists to broadly interpret the meaning of “sexual acts.” This made a wide range of behaviors punishable as crimes.

During the war, another group of civil servants—diplomats from the German Foreign Office—played a vital role in negotiating with leaders and officials of countries from which the Nazi regime was seeking to deport Jews.

German judges shared other civil servants’ conservative, nationalistic, and authoritarian outlook and acceptance of the legitimacy of the Nazi regime. Judges did not challenge the constitutionality of new laws passed in 1933 that rolled back political freedoms, rights, and protections provided citizens, including members of minority groups, granted under democratic constitution of the Weimar Republic. Most judges not only upheld the law in the years of Nazi rule but interpreted it in broad and far-reaching ways that facilitated, rather than hindered, the regime’s ability to carry out its anti-Jewish and racial policies. In cases involving the severance of legal contracts, such as those governing employee-employer relations, judges seldom exercised the usual latitude of interpretation given them in the direction of benefiting a Jew. For instance, in one breach of contract case, a judge interpreted being Jewish as a “disability” and grounds for dismissal from a workplace.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have affected the choices civil servants made as the Nazi government consolidated its power in the 1930s?

How did German professionals and civil servants contribute to the persecution of Jews and other groups?

Consider the roles of these professionals. How might their oaths and traditional responsibilities have been tested in times of governmental or social change?