Oskar Schindler

Oskar Schindler is one of the most famous rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. During World War II, Schindler ran a factory that employed Jewish forced laborers from the Kraków ghetto. After witnessing the Nazis’ brutality and violence against Jews, Schindler decided to protect as many Jewish forced laborers as he could.

Key Facts

-

1

Oskar Schindler was an opportunist, a German spy, and a member of the Nazi Party. He came to German-occupied Kraków in 1939 to try to get rich.

-

2

Schindler helped over 1,000 Jews survive the Holocaust.

-

3

Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-winning film Schindler’s List (1993) made Oskar Schindler a household name.

The responses of non-Jewish individuals to the Holocaust varied and depended on many factors. Most individuals were reluctant to help Jews because of fear, self-interest, greed, antisemitism, and political or ideological beliefs. Others chose to help because of religious or moral conviction, or based on the strength of personal relationships. This article is about Oskar Schindler, a member of the Nazi Party who eventually helped rescue Jews.

Introduction

Oskar Schindler (1908–1974) is one of the most famous rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. He helped more than 1,000 Jewish people survive. But in many ways, Schindler was an unlikely person to become a rescuer.

During the Holocaust, people chose to help Jews for a variety of reasons. Many rescuers cited their religious beliefs or their moral or ethical principles. But Oskar Schindler was not religious. Nothing in his biography suggests a man of moral integrity. He was a greedy opportunist, a German spy, and a member of the Nazi Party. He had numerous extramarital affairs. He repeatedly mismanaged his finances and failed to pay back loans. Schindler was 31 years old when he came to Kraków in German-occupied Poland, intent on getting rich.

Over the course of his years in Kraków, Schindler underwent a slow transformation. He eventually decided to use his new wealth and his position of influence to help Jews.

The apparent contradiction between Schindler’s character and his actions is one reason so many people are interested in Schindler.

Oskar Schindler: Background

Oskar Schindler was born on April 28, 1908, in Zwittau, Austria-Hungary (today Svitavy, Czechia). When the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved at the end of World War I, Schindler became a citizen of newly-established Czechoslovakia. Schindler was an ethnic German. This meant that Schindler spoke German and considered himself a German.

In 1928, Schindler married Emilie Pelzl. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, he held a variety of jobs. Like other male Czechoslovak citizens, Schindler served a brief, mandatory period in the military.

Schindler the Nazi

Even though Schindler did not live in Nazi Germany in the 1930s, his involvement in the Nazi movement dates to the mid-1930s. At that time, Nazi support was growing among ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia. In 1935, Schindler joined Konrad Henlein’s Sudeten German Party (Sudetendeutsche Partei). But Schindler’s involvement with Nazi Germany went beyond his membership in this political party.

By 1936, Schindler was working as a spy for Nazi Germany. He was an agent of the German military’s intelligence office, called the Abwehr. The Czechoslovak police imprisoned him for these traitorous activities in July 1938. Schindler, however, avoided further consequences for his crimes. Shortly after his arrest, Nazi Germany annexed the Sudetenland (a largely German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia) as part of the Munich Agreement. As a result, Schindler was released from prison in October 1938. He promptly applied for membership in the Nazi Party. In February 1939, he received provisional membership.

After his release, Schindler continued to work for the Abwehr. He supported Nazi Germany’s territorial aggression against Czechoslovakia and Poland. In March 1939, Nazi Germany invaded and occupied the Czech lands, which the Nazis then governed as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Then, on September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II.

Schindler’s Takeover of Jewish-Owned Businesses in Occupied Poland

After the German invasion and occupation of Poland, Schindler moved to occupied Kraków. At the time, he was still working for the Abwehr as an intelligence asset, although his exact assignment is unclear.

In Kraków, Schindler became a war profiteer. The Nazi German authorities had quickly begun confiscating private property from both Jewish and non-Jewish Poles. Schindler joined this process of widespread plunder. He eventually took over several confiscated businesses, hoping to use them to make a fortune.

Most notably, Schindler leased and later purchased Rekord, Ltd., a Jewish-owned enamelware manufacturer. Schindler’s takeover of Rekord, Ltd. in fall 1939 was carried out through the official German expropriation process.

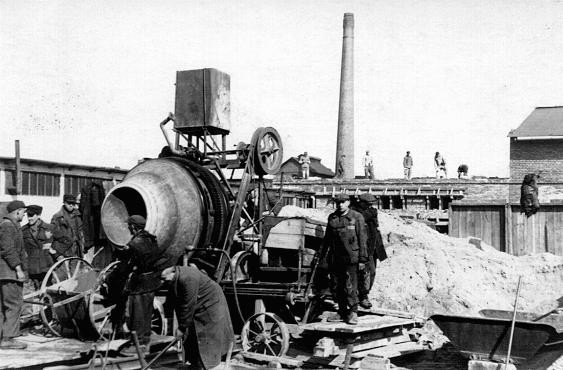

The Rekord, Ltd. factory produced enamel pots and pans. Schindler changed the business’s name to Deutsche Emailwarenfabrik (German Enamelware Factory, or DEF). The factory was often called “Emalia” (the Polish word for “enamel”). Schindler also ran two other businesses in Kraków, at least one of which he stole from its Jewish owners.

Schindler was not a particularly good businessman. He relied on some of the previous owners, in particular Abraham Bankier, to run Emalia. Bankier, who was Jewish, had been a part owner of Rekord, Ltd. and managed the factory before the war.

Jewish Forced Laborers at Schindler’s Emalia Factory, 1940–1943

Oskar Schindler took full advantage of the exploitative labor system that German authorities created in occupied Poland.

At first, most of Schindler’s factory workers were non-Jewish Poles. The only Jews he employed were Bankier and several other managers. At some point in 1941 or 1942, Schindler began to employ Jewish forced laborers from the Kraków ghetto at the Emalia factory.

Schindler used Jewish forced laborers because it was cheaper than paying non-Jewish Polish workers. In German-occupied Poland, factory owners like Schindler typically did not pay Jewish forced laborers for their work. Instead, they paid a daily rental fee to the SS.

Factory owners had free rein to abuse and overwork Jewish forced laborers. But survivor accounts indicate that Schindler treated his workers well at Emalia.

Schindler’s Intervention in a Deportation Action, June 1942

The Germans’ mistreatment and murder of Jews directly affected Schindler and his factory. In the summer of 1942, German authorities began deporting thousands of Jews from the Kraków ghetto to the Belzec killing center. In June, fourteen of Emalia’s Jewish forced laborers, including Abraham Bankier, were rounded up for deportation. Schindler personally intervened to save them from deportation. It is clear that he needed them to keep his factory running. But it is unclear if at that time Schindler knew the train’s destination or about the Belzec killing center. Regardless of his motivations, Schindler’s intervention almost certainly saved their lives.

Schindler’s Contacts with a Jewish Rescue Group

In addition to his own efforts to help Jewish prisoners in Kraków, Schindler also established ties with a broader Jewish aid network.

Beginning in late 1942, Schindler began to work with the Relief and Rescue Committee. This was a Jewish aid organization based out of Budapest, Hungary. It was led by Hungarian Jews, including Joel Brand and Rudolf Kasztner. Schindler served as a courier. He helped Jewish prisoners by passing them money, letters, and information.

In November 1943, Schindler traveled to Budapest. There, he gave the committee information about the mass murder of Jews in German-occupied Poland.

Schindler’s Protection of Jews During the Destruction of the Kraków Ghetto, March 1943

Schindler became more directly involved in helping Jews in 1943. That March, the Germans dissolved the Kraków ghetto and murdered many of its remaining residents. During the liquidation of the ghetto, Schindler protected his Jewish workers by instructing them to stay at the factory overnight. As a result, these Jewish workers survived the brutal and deadly action. Afterwards, those prisoners who worked at Emalia were sent from the ghetto to the nearby Plaszow forced labor camp.

The driving motives for my actions and my inner change were the daily witnessing of the unbearable suffering of Jewish people and the brutal occupation… in the occupied territories.

—Oskar Schindler

Emalia as a Refuge for Jewish Prisoners of Plaszow, 1943–1944

After the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto, Schindler continued to use Jewish forced laborers at Emalia. At first, these forced laborers lived at the Plaszow labor camp and traveled to work at Emalia several kilometers away. Later, they were housed in a camp at Schindler’s factory.

Schindler’s Friendship with Plaszow Commandant Amon Göth

At Plaszow, prisoners were subjected to extreme hardship and random acts of violence under SS commandant Amon Göth. Göth ran Plaszow from February 1943 to September 1944. He was infamous for his excessive and sadistic cruelty. He often shot at prisoners from the balcony of his villa. He also carried out arbitrary executions. Schindler befriended Göth and attended drunken parties at Göth’s villa. Schindler used this personal relationship and bribery to get favors from the commandant. This allowed Schindler to operate his factory more successfully, as well as to help Jewish prisoners.

Schindler’s Camp at Emalia, 1943–1944

At some point in 1943, Schindler convinced Göth to allow Jewish forced laborers to live full time outside of Plaszow in a camp at Emalia. The camp was located on the Emalia factory complex grounds. The Jewish forced laborers who lived in the camp worked for Emalia and three other nearby factories.

Conditions at the Emalia camp were much better than at the Plaszow main camp. Schindler and Austrian factory owner Julius Madritsch obtained extra food for the prisoners on the black market.

In January 1944, the SS changed the designation of Plaszow from a forced labor camp to a concentration camp. The Emalia camp was officially called the Zabłocie subcamp. There were about 1,450 Jewish prisoners in the subcamp in summer 1944.

At some point in 1943 or 1944, Schindler added an armaments factory to Emalia. Jewish prisoners built the factory, which was completed in late summer 1944.

The End of Schindler’s Emalia Camp, Summer 1944

In summer 1944, the Soviet army advanced into Poland and toward Kraków. The German authorities began to evacuate prisoners from Plaszow and its subcamps, including Emalia. The authorities also ordered the relocation of armaments factories in German-occupied Poland into the interior of Germany. This included Schindler’s armaments factory at Emalia.

Hundreds of Jewish prisoners were removed from Schindler’s protection when they were sent from Emalia back to Plaszow. Many were immediately placed in overcrowded freight cars. They were then transferred to the Mauthausen concentration camp. Some prisoners recalled how Schindler tried to help them in a small but meaningful way, even at the last moment. He bribed Göth and the SS guards to give the prisoners water at the station in Plaszow and en route to Mauthausen. Once the train left Plaszow, Schindler could no longer help these people.

Schindler’s efforts at Emalia were still important. Schindler had ensured that the Emalia prisoners had been protected and relatively well-fed at the factory. This meant they had a better chance of surviving the extreme conditions at Mauthausen.

At this point, only about 300 male Jewish prisoners remained at Emalia with Schindler. Their task was to help Schindler take down the armaments factory and prepare to move it to another location.

Moving the Armaments Factory to Brünnlitz, Fall 1944

In fall 1944, Schindler received permission to relocate his armaments plant to the town of Brünnlitz (Brněnec) in the Sudetenland.

The Brünnlitz factory camp was a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. German authorities transferred about 1,000 Jewish prisoners from Plaszow to Brünnlitz to work in Schindler’s factory there. This included 700 men and 300 women. For the Jewish prisoners of Plaszow, being transferred to Brünnlitz meant a greater chance of survival. Those sent to other concentration camps faced more dire conditions.

Did Oskar Schindler Create a List?

Oskar Schindler did not create a list. The concept of “Schindler’s list” is a shorthand for Schindler’s rescue efforts during the Holocaust. It is commonly understood to mean a list of prisoners rescued by Schindler. More specifically, it is often associated with the names of the prisoners who were transferred from the Plaszow concentration camp to Schindler’s Brünnlitz factory.

There was not just one Plaszow-to-Brünnlitz transfer list. There were separate lists for men and women. The names on the lists changed several times. Furthermore, these transfer lists were not written by Schindler, and Schindler did not have final say over the names. The lists were actually prepared by Marcel Goldberg. Goldberg was a Jewish prisoner functionary who served as a clerk for the SS in the Plaszow main camp. He compiled separate lists of male and female prisoners to be transferred to Schindler’s factory in Brünnlitz.

The lists compiled by Goldberg included some of the Jewish workers from both Schindler and Madritsch’s factories, as well as their family members. The lists also included prominent Jewish prisoner functionaries and their families. Some prisoners bribed Goldberg to be added to the list. Others were just lucky.

Most people transferred from Plaszow to Brünnlitz had not worked for Oskar Schindler at Emalia. At the time, Schindler did not know most of them personally.

The Prisoner Transports to Brünnlitz, Fall 1944

The process of transporting prisoners from Plaszow to Brünnlitz was chaotic. During the transport, the prisoners were temporarily removed from Schindler’s supervision, and he could not protect them.

The male prisoners were transferred to Brünnlitz by way of Gross-Rosen. They arrived in Brünnlitz after just a few days. However, the women were transferred by way of Auschwitz-Birkenau. They were held there for three weeks. For the female prisoners, the time they spent in Auschwitz-Birkenau was terrifying, dangerous, and degrading. One older female prisoner contracted Typhus and died. The women eventually arrived at the Brünnlitz camp in mid-November 1944. It is likely that Schindler intervened via a messenger to secure their release. Contrary to popular misconception, he did not go in person.

At both Gross-Rosen and Auschwitz, a few prisoners were removed from the Brünnlitz transport lists and replaced with other prisoners.

Schindler’s Rescue Efforts at Brünnlitz

Schindler’s most significant rescue efforts took place at the Brünnlitz camp, during the last desperate months of World War II. From the establishment of the camp in October 1944 until its liberation in May 1945, Schindler devoted himself to saving its Jewish prisoners. This was a difficult and risky endeavor that required him to spend the fortune he had made in Kraków.

Protecting Prisoners from the SS

Because Brünnlitz was a subcamp of Gross-Rosen, it was run by an SS commandant and guarded by SS men. Schindler constantly feared that the SS commandant would decide to liquidate the camp and murder the Jewish inmates. To protect the Jewish prisoners from the SS, Oskar and Emilie Schindler lived in an apartment on site.

Acquiring Food and Medicine at Brünnlitz

At Brünnlitz, Emilie Schindler helped Oskar acquire scarce food and medicine. Schindler paid for these from his earnings. This was Emilie’s first significant role in Oskar’s rescue efforts. Locals also helped secretly supply the prisoners with food.

Falsifying Production Numbers to Save Jews

The Brünnlitz plant was classified as an armaments factory. This was essential to its continued existence. Schindler claimed that the prisoners were all skilled workers producing armaments for the German war effort. In reality, not everyone was working in the factory. Those who were did not accomplish much. In total, the factory produced only one wagonload of ammunition.

With the help of Jewish prisoners Itzhak Stern and Mietek Pemper, Schindler created fake production figures to deceive the Nazi German authorities. This deception was necessary to prevent the SS from shutting down the camp.

Helping Other Prisoners

When other prisoners arrived in the area, the Schindlers chose to care for them at Brünnlitz. In total, three transports of prisoners arrived from other camps. The Schindlers brought them into Brünnlitz, where they received medical care and food.

On April 18, 1945, a prisoner list for Brünnlitz showed 1,098 names (801 men and 297 women). It included both the names of Jews transferred from Plaszow and the new arrivals. This list is also sometimes considered “Schindler’s list.”

Liberation

The Brünnlitz camp was liberated in May 1945. The Schindlers left Brünnlitz on May 9, 1945, just before the Soviet troops arrived at the camp. They fled west, fearful of falling into Soviet hands. Before he left, the Jewish prisoners gave Oskar a gold ring and a signed statement attesting to his efforts to help them. The Schindlers eventually made it to the American Zone of Allied-occupied Germany.

Schindler’s Life After World War II

After World War II, Schindler and his wife could not return to Czechoslovakia. His prewar activities as a German spy made him a war criminal there. His ethnic German background also made him unwelcome in postwar Czechoslovakia. After World War II, the country expelled its ethnic German population.

The Schindlers settled for several years in the town of Regensburg, in the American occupation zone of Germany. There, they struggled financially. Schindler repeatedly turned to his former Jewish prisoners and Jewish aid organizations for help. He sought financial compensation from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (the Joint) for the money he had spent to rescue Jews. Schindler claimed he had spent 2.64 million Reichsmarks (about one million US dollars at the time). Later, he also applied for compensation for his factory losses with the West German government.

In 1949, Oskar and Emilie immigrated to Argentina. There, Oskar tried and failed to establish a successful business. He fell into debt. In 1957, Schindler returned alone to Germany. He permanently separated from Emilie, but they did not divorce. Schindler died in Germany in October 1974. He is buried in Israel.

Many of the Jewish people whom Schindler had helped remained devoted to him after the war. They are often referred to as Schindlerjuden or Schindler Jews.

Making Schindler a Household Name

Oskar Schindler was not famous during World War II. He became a well-known name after the war, thanks to the efforts of the Schindler Jews.

Beginning in the 1940s, some Schindler Jews began publicizing Schindler’s story. In the twentieth century, the story of Schindler appeared in newspapers, books, and films. In 1957, an essay by Schindler was included in a German book about rescuers during the Holocaust.

The 1993 movie Schindler’s List made Oskar Schindler into a household name. Directed by Steven Spielberg, the film received popular and critical acclaim. It won seven Oscars, including Best Picture at the 1994 Academy Awards. Spielberg’s film was based largely on the 1982 novel Schindler’s List (originally titled Schindler’s Ark) by Thomas Keneally. Keneally worked closely with Leopold Page, one of the Jewish men saved by Schindler.

The novel and the film introduced the American public to Schindler’s story. However, both accounts contain some inaccuracies.

Schindler as Rescuer

Oskar Schindler’s unscrupulousness and opportunism made him an effective protector of his Jewish prisoners. But these same traits also led Schindler to behave in less honorable ways. Because of this, his status as a rescuer has been controversial.

For example, in the 1960s, his nomination as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, Israel’s national institution of Holocaust commemoration, was contentious. Many Schindler Jews supported his nomination. However, two Jewish men from Kraków credibly accused Schindler of theft and abuse during the early years of World War II. Despite these accusations, Schindler was invited by Yad Vashem to plant a tree in his honor. His planting ceremony took place on May 8, 1962.

In late 1963, the committee that awarded the title “Righteous Among the Nations” decided not to formally extend the honor to Schindler. In 1993, Yad Vashem reversed its earlier decision and awarded both Oskar and Emilie Schindler the title.

Oskar Schindler is widely remembered as a heroic rescuer during the Holocaust. His story demonstrates the complexities and challenges of rescue.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

In 1943, the camp at Emalia was sometimes called a Judenlager (Jew camp) or a Nebenlager (auxiliary camp). It was subordinate to Plaszow.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have influenced Schindler's decisions?

Are these factors unique to this history or universal?

How can societies, communities, and individuals reinforce and strengthen the willingness to stand up for others?